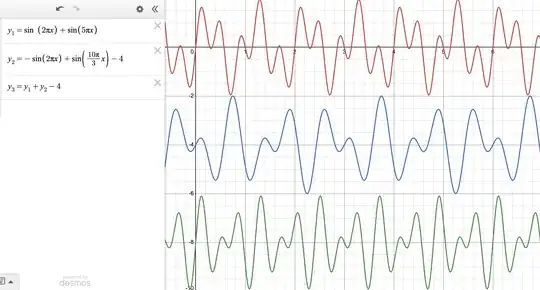

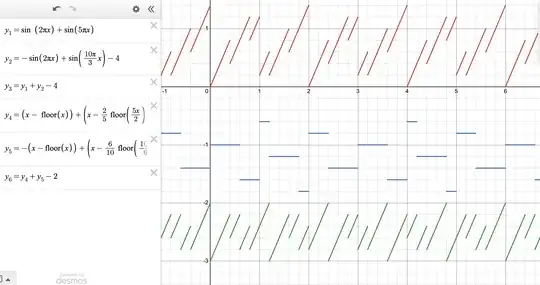

Here is the question: Let $f,g$ be $2$ functions with shortest period $t_1=2$ and $t_2=3$ respectively. Is it true that $h:=f+g$ has shortest period $6$?

My thoughts:

It is in general not true that if $t_1,t_2$ are commensurate, then $t:=\mathrm{lcm}(t_1,t_2)$ is the shortest period of $h$. But all the counter-examples I have seen are the case when $t_1=t_2$, for example, $f=\sin x$ and $g=-\sin x$. Are there any counter-examples with $t_1\neq t_2$, even with $\gcd(t_1,t_2)=1$? (related: Period of the sum/product of two functions)

If we further add the continuous condition of both $f$ and $g$, then according to The sum of two continuous periodic functions is periodic if and only if the ratio of their periods is rational? $h$ cannot have irrational period, and if it has a shorter rational period $\frac{p}{q}$ with $\gcd(p,q)=1$, then $$ \begin{cases} 3\mid 2p\\ 2\mid 3p \end{cases}\Rightarrow 6\mid p$$ Now $\frac{6r}{q}$ ($\gcd(r,q)=1$) is a period, so as $\frac{6q}{q}$, so as $\frac{6}{q}$. However, is it necessary that $q=1$? Or can we construct counter-examples in this case?

Any comments or solutions are welcomed. Thanks in advance!