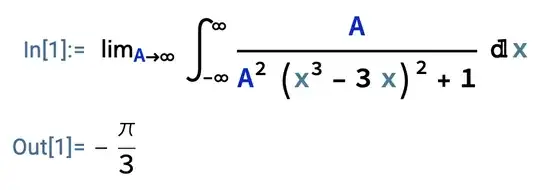

The failure of Karthik Vedula's method can be explained in many ways.

1. As other users pointed out, the use of DCT is incorrect as there is no integrable dominating function of the integrand. Indeed, for each $y \in \mathbb{R}$ there exists $A > 0$ such that

$$ \frac{y^3}{A^2} - 3y = 0. $$

Indeed, we can set $A = \frac{|y|}{\sqrt{3}}$ when $y \neq 0$, and we can choose any $A > 0$ when $y = 0$. Consequently.

$$ \sup_{A > 0} \frac{1}{\Bigl( \frac{y^3}{A^2} - 3y \Bigr)^2 + 1} = 1 $$

and this is the "minimal" dominating function for the family $\Bigl\{ \frac{1}{( (y^3/A^2) - 3y )^2 + 1} \Bigr\}_{A>0}$, which is clearly non-integrable. Hence DCT is not applicable here.

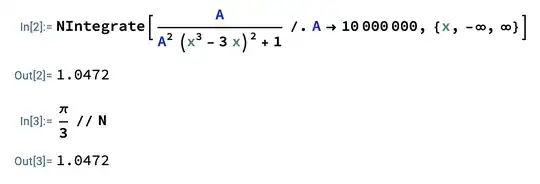

2. Of course, the failure of DCT does not necessarily imply that interchanging the order of limit and integral is not valid. So, let's take a closer look on how the integrand changes when $A$ grows. The above observation tells that the integrand has three peaks, one at $y = 0$ and the other two at $y = \pm \sqrt{3}A$. Now note that the last two peaks are pushed away towards infinity as $A \to \infty$:

Consequently, the "mass" concentrated about $\pm\sqrt{3}A$ are lost in the pointwise limit of the integrand as $A \to \infty$. This loss of mass accounts for the difference between the correct answer and the value obtained in Karthik Vedula's approach.

Addendum. Here is a more general version of the problem:

Theorem. Assume $f : \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}$ is a $C^1$-function such that the following conditions hold:

- $\int_{|x| > r} \frac{\mathrm{d}x}{|f(x)|^2} < \infty$ for some $r > 0$,

- $f(x)$ has only finitely many zeros $x_1, \ldots, x_N$, and

- $f'(x_i) \neq 0$ for each $i \in [1:N]$.

Then

$$ \lim_{A \to \infty} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \frac{A}{A^2f(x)^2 + 1} \, \mathrm{d}x = \pi \sum_{i=1}^{N} \frac{1}{|f'(x_i)|}. $$

Intuitively, this is because $\frac{A}{(Ay)^2 + 1}$ "converges to" $\pi \delta(y)$, hence

$$ \lim_{A \to \infty} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \frac{A}{A^2f(x)^2 + 1} \, \mathrm{d}x

= \pi \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \delta(f(x)) \, \mathrm{d}x

= \pi \sum_{i=1}^{N} \frac{1}{|f'(x_i)|}. $$

To make this claim more rigorous, let $\delta > 0$ be such that

the open intervals $B_\delta(x_i) = (x_i-\delta, x_i+\delta)$ are disjoint, and

each restriction $f_i = f|_{B_{\delta}(x_i)}$ is a $C^1$-bijection from $B_\delta(x_i)$ to its image $f(B_\delta(x_i))$ with $C^1$-inverse for each $i \in [1:N]$.

Such a $\delta > 0$ exists by the inverse function theorem. For simplicity, write $U = \bigcup_{i=1}^{N} B_\delta(x_i)$. Then

$$

\begin{align*}

&\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \frac{A}{A^2f(x)^2 + 1} \, \mathrm{d}x \\

&= \sum_{i=1}^{N} \int_{B_\delta(x_i)} \frac{A}{A^2f(x)^2 + 1} \, \mathrm{d}x

+ \int_{B_r(0) \setminus U} \frac{A}{A^2f(x)^2 + 1} \, \mathrm{d}x

+ \int_{B_r(0)^c \setminus U} \frac{A}{A^2f(x)^2 + 1} \, \mathrm{d}x,

\end{align*}

$$

where $r > 0$ is as in the statement of the theorem. Now we estimate each term separately:

For each $i$, substituting $y = A f_i(x)$ yields

$$

\begin{align*}

\int_{B_\delta(x_i)} \frac{A}{A^2f(x)^2 + 1} \, \mathrm{d}x

&= \int_{A\cdot f(B_\delta(x_i))} \frac{|(f_i^{-1})'(y/A)|}{y^2 + 1} \, \mathrm{d}y.

\end{align*}

$$

Note that $f(B_\delta(x_i))$ is an open interval containing $0$, hence $A\cdot f(B_\delta(x_i))$ expands to $(-\infty, \infty)$ as $A \to \infty$. So by DCT,

$$

\begin{align*}

\lim_{A\to\infty} \int_{B_\delta(x_i)} \frac{A}{A^2f(x)^2 + 1} \, \mathrm{d}x

&= \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \frac{|(f_i^{-1})'(0)|}{y^2 + 1} \, \mathrm{d}y

= \frac{\pi}{|f'(x_i)|}.

\end{align*}

$$

For the second term, note that

$$ m := \inf_{x \in B_r(0) \setminus U} |f(x)| > 0. $$

(To see why, apply the extremum value theorem to the continuous function $|f|$ on the compact set $\overline{B_r(0)} \setminus U$.) Consequently,

$$

\left| \int_{B_r(0) \setminus U} \frac{A}{A^2f(x)^2 + 1} \, \mathrm{d}x \right|

\leq \int_{B_r(0) \setminus U} \frac{A}{A^2m^2 + 1} \, \mathrm{d}x

\leq \frac{2rA}{A^2m^2 + 1} \to 0.

$$

For the last integral,

$$

\int_{B_r(0)^c \setminus U} \frac{A}{A^2f(x)^2 + 1} \, \mathrm{d}x

\leq \int_{B_r(0)^c} \frac{A}{A^2f(x)^2} \, \mathrm{d}x

= \frac{1}{A} \int_{B_r(0)^c} \frac{\mathrm{d}x}{f(x)^2}

\to 0.

$$

Combining altogether, the desired claim follows.