The main connection is done by relating the AGM to an integral, as mentioned on the wiki page:

Arithmetic Geometric Mean: Proof of the integral form expression

With almost the same notations ($\theta$ replaced by $t$ for an easy typing) we introduce:

$$

I(x,y) := \int_0^{\pi/2}\frac {dt}{\sqrt{x^2\cos^2t+y^2\sin^2t}}

\ .

$$

For given $x>y>0$ denote by $x',y'$ their arithmetic, respectively geometric mean. The main property of $I$ is its invariance w.r.t. the one-step AGM-passage from $(x,y)$ to $(x',y')$. So further steps also invariate $I$, i.e. $$I(x,y)=I(x',y')=I(x'',y'')=\dots\ .$$

The sequence in $\Bbb R^2$ with terms $(x,y)$, $(x',y')$, $(x'',y'')$, ... is convergent to an element of the shape $(m,m)$ because of the "sandwich" chain $y\le y'\le y''\le \dots\le x''\le x'\le x$. (The limit must have two equal components, since it is fixed by applying a new AGM-step.) We denote by $\operatorname{AGM}(x,y)$ this first or second component $m$.

We have $\displaystyle I(m,m)=

\int_0^{\pi/2}\frac {dt}{\sqrt{m^2\cos^2t+m^2\sin^2t}}

=\int_0^{\pi/2}\frac {dt}m=\frac\pi{2m}$. This gives a formula for $m:=\operatorname{AGM}(x,y)$ in terms of the integral $I(x,y)$:$$

\bbox[lightgreen]{\qquad\color{blue}{\operatorname{AGM}(x,y)=\frac\pi{2I(x,y)}\ .\qquad}}$$

Let us now be specific, and start with $x=\sqrt 2$, $y=1$.

So we want to show that the denominator in the above

formula is $2I(\sqrt2, 1)=\varpi$. Let us "compute" (or rather reshape) $2I(\sqrt2, 1)$.

Write below $\sin^2 t=1-\cos^2 t$ and substitute $u=\cos t$, $t=\arccos u$, $dt=-\frac{du}{\sqrt{1-u^2}}$, the minus sign exchanges the corresponding integration extremities:$$

\small

\begin{aligned}

2I(\sqrt 2, 1)&=

2\int_0^{\pi/2}\frac 1{\sqrt{2\cos^2t+\sin^2t}}\cdot dt

=

2\int_0^1

\frac 1{\sqrt{1+u^2}}

\cdot

\frac {du}{\sqrt{1-u^2}}

\\

&=

2\int_0^1

\frac {du}{\sqrt{(1+u^2)(1-u^2)}}

=

2\int_0^1

\frac {du}{\sqrt{1-u^4}}\overset?=\varpi\ .

\end{aligned}

$$The $?$-sign above the equality sign suggests the fact

that we have to show the equality:

$$

2\int_0^1

\frac {du}{\sqrt{1-u^4}}\overset?=\varpi\ .

$$

We may consider it as "known", or as a definition, but in our case, the lemniscate is the foreground object in the question,

so let us connect the two

sides of the $\overset?=$ by an argument. We thus compute the arc length of the "standard" lemniscate, and take its perimeter as $2\varpi$ - as a definition of $\varpi$.

Note that after a substitution $v=u^4$, $u=v^{1/4}$, $du=\frac 14v^{1/4-1} dv$ the last integral becomes a beta-integral, see also Beta Function on Wolfram mathworld on such integrals:

$$

\int_0^1

\frac {du}{\sqrt{1-u^4}}

=\frac 14\int_0^1 v^{\frac 14-1}(1-v)^{\frac 12-1}\;dv

=\frac 14B\left(\frac 14,\frac 12\right)

=\frac 14

\frac{\Gamma\left(\frac 14\right)\Gamma\left(\frac 12\right)}

{\Gamma\left(\frac 34\right)}\overset{\boldsymbol{\color{green}*}}=

\\

\frac 14

\frac{\Gamma\left(\frac 14\right)^2}

{\sqrt{2\pi}}

\overset{\boldsymbol{\color{green}{**}}}=\frac 1{4\sqrt2}

\frac{\Gamma\left(\frac 14\right)^2}

{\Gamma\left(\frac 12\right)}

=\frac 1{4\sqrt2}

\color{blue}{B\left(\frac 14,\frac 14\right)}

\ .

$$Here, at $\boldsymbol{\color{green}*}$ we have used the "duplication formula" for the gamma function,

$\displaystyle \Gamma\left(\frac 14\right)\Gamma\left(\frac 34\right)

=\sqrt{2\pi}\cdot\Gamma\left(\frac 12\right) \implies \frac{\Gamma\left(\frac 12\right)}{\Gamma\left(\frac 34\right)}

=\frac{\Gamma\left(\frac 14\right)}{\sqrt{2\pi}} $, while at $\boldsymbol{\color{green}{**}}$ the relation $\Gamma\left(\frac 12\right)=\sqrt \pi.$

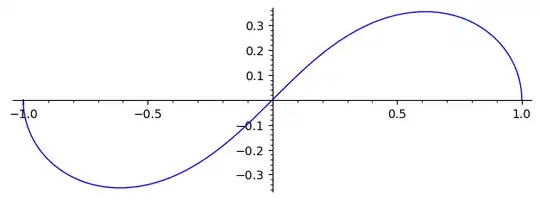

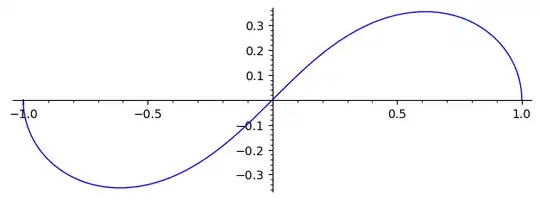

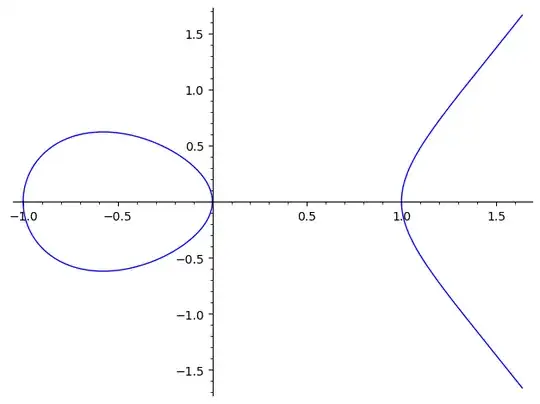

We introduce now $\varpi$ in the context of the lemniscate of Bernoulli. A half part of the lemniscate (which "looks like" $\infty$) is rationally parametrized by:$$t \to(x(t),y(t))=\left(\ \frac{t+t^3}{1+t^4}\ ,\ \frac{t-t^3}{1+t^4}\ \right)

\ ,\qquad t\in[-1,1]\ .$$

(It is "the $\infty$ without the $\sim$".) Here is a plot of the image of this parametrization:

Generated in sage via:

var('t'); parametric_plot( ( (t+t^3)/(1+t^4), (t-t^3)/(1+t^4) ), (t, -1, 1) )

The length $\varpi$, defined using the lemniscate, is the length of this parametrized curve $t\to (x(t),y(t))$:

$$

\small

\begin{aligned}

\varpi

&=\int_{-1}^1\|(x'(t),y'(t)\|\;dt

=

\int_{-1}^1\left\|

\

\frac{( 1 - 4t^2 + t^4 )(1 + t^2)}

{(1+t^4)^2}

\ ,\

\frac{( 1 + 4t^2 + t^4 )(1 - t^2)}

{(1+t^4)^2}

\

\right\|

\; dt

\\

&=

\int_{-1}^1

\left(\ ( 1 + 4t^2 + t^4 )^2(1 - t^2)^2 + ( 1 + 4t^2 + t^4 )^2(1 - t^2)^2

\ \right)^{1/2}

\;\frac{dt}{(1+t^4)^2}

\\

&=

\int_{-1}^1

\left(\

\begin{array}{c}

(t^{12} + 6t^{10} + 3t^8 - 20t^6 + 3t^4 + 6t^2 + 1)

\\ + \\

(t^{12} - 6t^{10} + 3t^8 + 20t^6 + 3t^4 - 6t^2 + 1)

\end{array}

\ \right)^{1/2}

\;\frac{dt}{(1+t^4)^2}

\\

&=

\int_{-1}^1

\left(\

2(t^{12} + 3t^8 + 3t^4 + 1)

\ \right)^{1/2}

\;\frac{dt}{(1+t^4)^2}

=

\int_{-1}^1

\left(\

2(t^4 + 1)^3

\ \right)^{1/2}

\;\frac{dt}{(1+t^4)^2}

=

\sqrt 2\int_{-1}^1\frac{dt}{\sqrt{1+t^4}}

\\

&=

2\sqrt 2\int_0^1\frac{dt}{\sqrt{1+t^4}}

\\

&=

2\sqrt 2\int_1^\infty\frac{dt}{\sqrt{1+t^4}}\qquad

\text{(using the substitution $t\to \frac 1t$)}

\\

&=

\sqrt 2\int_0^\infty\frac{dt}{\sqrt{1+t^4}}\qquad

\text{(and using now $s=t^4$, $t=s^{1/4}$, $dt=\frac 14s^{3/4}$)}

\\

&=

\frac{\sqrt 2}4\int_0^\infty\frac{s^{3/4}}{(1+s)^{1/2}}\;dt

=

\frac{\sqrt 2}4\int_0^\infty\frac{s^{\frac14-1}}{(1+s)^{\frac 14+\frac 14}}\;dt

\\

&\overset{\boldsymbol{\color{red}*}}=\frac{\sqrt 2}4

\color{blue}{B\left(\frac 14,\frac 14\right)}

=2\int_0^1

\frac {du}{\sqrt{1-u^4}}\ .

\\[3mm]

&\qquad\text{ At ${\boldsymbol{\color{red}*}}$ we used the integral form for the Beta function $B$ with $m=n=\frac 14$:}

\\

B(m,n)&:=

\int_0^1

x^{m-1}x^{n-1}\; dx

\qquad\text{ (using $x=\frac s{1+s}=1-\frac 1{1+s}$, $dx=\frac {ds}{(1+s)^2}$})

\\

&=

\int_0^\infty

\frac{s^{m-1}}{(1+s)^{m-1}}

\cdot

\frac 1{(1+s)^{n-1}}

\cdot

\frac {ds}{(1+s)^2}

=

\int_0^\infty

\frac{s^{m-1}}{(1+s)^{m+n}}

\; ds

\ .

\end{aligned}

$$

Above we have finally connected $\varpi$ with the AGM-integral

$\int_0^1

\frac {du}{\sqrt{1-u^4}}$

via $\color{blue}{B\left(\frac 14,\frac 14\right)}

$. This is one among many relations in the chain of possible

equivalent forms for $\varpi$. We could stop here, because $(*)$ is holding.

But there is one more important connection to an elliptic curve, that may be of interest.

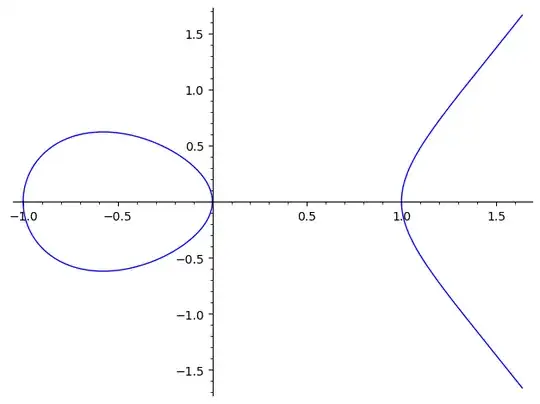

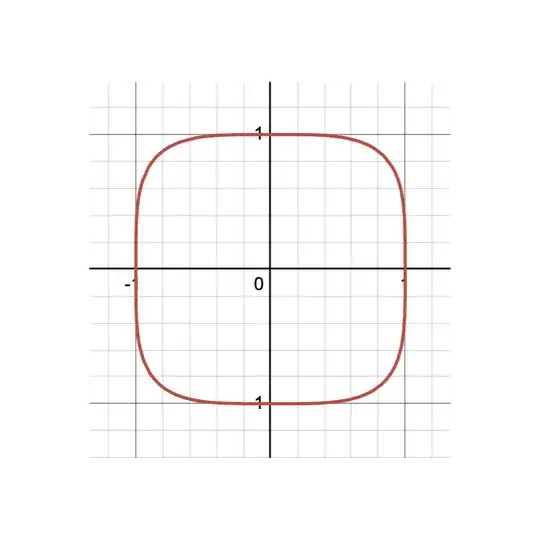

The related elliptic curve $E$ is (in affine shape)

$$E\ :\qquad y^2=x^3-x\ ,$$

and need to join the integral

of $1/\sqrt{1-t^4}$ on $[0,1]$

with the integral of the invariant differential $dx/y$ on this elliptic curve between the points with $x=1$ and $x=\infty$ (which make sense after passing from the affine world to the projective world), this is done by the substitution $x=1/t^2$, $dx=-2\cdot\frac1{t^3}\; dt$,

$$

\small

\int_{x=1}^{x=\infty}

\frac{dx}{y}

=

\int_1^\infty\frac{dx}{\sqrt{x^3-x}}

=

2

\int_0^1

\frac{dt}{t^3\cdot\sqrt{t^{-6}-t^{-2}}}

=

2

\int_0^1

\frac{dt}{\sqrt{t^6(t^{-6}-t^{-2})}}

=\\

2

\int_0^1

\frac{dt}{\sqrt{1-t^4}}=\varpi

\ .

$$

For the elliptic curve $E$ the associated lattice has the periods $2\varpi$ and $2\varpi\cdot i$. The following sage code gives numeric support for this:

sage: E = EllipticCurve(QQ, [-1, 0])

sage: E

Elliptic Curve defined by y^2 = x^3 - x over Rational Field

sage: L = E.period_lattice()

sage: L.0

2.62205755429212

sage: L.1

2.62205755429212*I

sage: var('t');

sage: 2*integral( 1/sqrt(1-t^4), t, 0, 1 ).n()

2.62205755429212

Later EDIT: Above we have an explicit connection between the two integrals $\int_0^1\frac{dt}{\sqrt{1-t^4}}$ and $\int_1^\infty\frac{dx}{\sqrt{x^3-x}}$. Both integrals are mentioned in the chain of possible equivalent forms for $\varpi$. Both integrals make it possible to see the integral as an integral on an algebraic object, which is an elliptic curve. I will say something more to the last integral involving $dx$. It is hard here to give in a few words an introduction to the reach structure related to an elliptic curve, but i am trying to mention without proof a web of specific mathematical instances that make this object an interesting object to study. In the last integral we formally write $y$ for the denominator, $y=\sqrt{x^3-x}$. Squaring leads to the algebraic equation of an affine curve in Weierstraß form,$$E\ :\qquad y^2 =x^3-x\ .$$This is the curve

sage: E = EllipticCurve(QQ, [-1, 0])

sage: E.label()

'32a2'

with the human label 32a2, and we can take a closer look at it on the LMFDB page, after a search of this label. On the subpage LMFDB - elliptic curves we type this label into the corresponding field, and we are linked to www.lmfdb.org/EllipticCurve/Q/32a2. At one place there is listed the real period, $\Omega$, which is $2\varpi$ on this page, by the used convention. It has two real components, which is the reason for the inserted factor two. In a picture:

$y^2=x^3-x$" />

$y^2=x^3-x$" />

Now why is this object interesting (from an arithmetic point of view)? It is so because $E$, more exactly its projective/homogenized version $Y^2Z=X^3-XZ^2$ which also contains the infinity point $\infty=O=[X_\infty:Y_\infty:Z_\infty]=[0:1:0]$, comes with a reach structure, its algebraic (and/or real and/or complex) points can be added, so we have an algebraic group $(E(\Bbb C),\oplus)$ with an addition operation $\oplus$ which is defined algebraically (i.e. using fractions of polynomials in $x,y$ in a generic case). For instance, for each point $T=(x_T,0)$ in the list $(0,0)$, $(1,0)$, $(-1,0)$, we have $T\oplus T=O$. (The infinity point $O$ is the neutral element w.r.t. $\oplus$, the three $T$-points are the two-torsion points. Counting also $O$ as torsion point we have in total four torsion points.)

There is a lot of information of the elliptic curve regarding its arithmetic, and we are performing the following game. As it comes, the curve $E$ is defined over $\Bbb Q$, in fact we have a model of it over the integers, its coefficients in the polynomial equation $y^2-x^3+x=0$ are all integers. We can now "break" the $\Bbb Z$-information into pieces, we possibly lose something, but we do so.

Let us consider this equation modulo some prime $p$ and "count points" modulo $p$, i.e. over the field $\Bbb F_p$, in the projective space, so we count also a point at infinity $O=\infty$. For instance, modulo five we have the eight points: $O=\infty$, $(0,0)$, $(\pm1,0)$, $(2,\pm 1)$, $(3,\pm 2)$. We now "compare" them with the number of points of the projective space $\Bbb P^1$, there are $5+1=6$ points. It turns out (by a theorem of Hasse) that the difference is "controlled". For the prime $5$ it is $a_5=\#\Bbb P^1(\Bbb F_5)-\#E(\Bbb F_5)=6-8=-2$. In a similar manner we compute:

$$

\small

\begin{aligned}

a_3 &= \#\Bbb P^1(\Bbb F_3) -\#E(\Bbb F_3 )=4-4=0\ ,\\

a_5 &= \#\Bbb P^1(\Bbb F_5) -\#E(\Bbb F_5 )=6-8=-2\ ,\\

a_7 &= \#\Bbb P^1(\Bbb F_7) -\#E(\Bbb F_7 )=8-8=0\ ,\\

a_{11} &= \#\Bbb P^1(\Bbb F_{11})-\#E(\Bbb F_{11})=12-12=0\ ,\\

a_{13} &= \#\Bbb P^1(\Bbb F_{13})-\#E(\Bbb F_{13})=14-8=6\ ,\\

a_{17} &= \#\Bbb P^1(\Bbb F_{17})-\#E(\Bbb F_{17})=18-16=2\ ,\\

a_{19} &= \#\Bbb P^1(\Bbb F_{19})-\#E(\Bbb F_{19})=20-20=0\ ,\\

a_{23} &= \#\Bbb P^1(\Bbb F_{23})-\#E(\Bbb F_{23})=24-24=0\ ,\\

a_{29} &= \#\Bbb P^1(\Bbb F_{29})-\#E(\Bbb F_{29})=30-40=-10\ ,\\

a_{31} &= \#\Bbb P^1(\Bbb F_{31})-\#E(\Bbb F_{31})=32-32=0\ ,\\

&\ \vdots

\end{aligned}

$$and so on. (Compare with the

coefficients of the form $q^p$ of the associated modular form.) These numbers $(a_p)$ carry the main arithmetic information in the "broken pieces" of filtering the integers through a prime numbers sieve, and in a similar manner to the construction of the Euler product for the Riemann zeta function, we can assemble the $(a_p)$ sequence into a similar product, see also the B-SD section on a page:

$$

\small

L(E,s)=

\frac 1{1+3^{1-2s}}\cdot

\frac 1{1+2\cdot 5^{-s}+5^{1-2s}}\cdot

\frac 1{1+7^{1-2s}}\cdot

\frac 1{1+11^{1-2s}}\cdot

\frac 1{1-6\cdot 13^{-s}+13^{1-2s}}\cdot

\dots

$$

We formally compute this $L$-series in $s=1$, and put together in a product the information from the prime places,

$$

\small

\begin{aligned}

L(E,1)&=

\frac 3{\#E(\Bbb F_{3})}\cdot

\frac 5{\#E(\Bbb F_{5})}\cdot

\frac 7{\#E(\Bbb F_{7})}\cdot

\frac {11}{\#E(\Bbb F_{11})}\cdot

\frac {13}{\#E(\Bbb F_{13})}\cdot

\frac {17}{\#E(\Bbb F_{17})}\cdot

\frac {19}{\#E(\Bbb F_{19})}\cdot

%\frac {23}{\#E(\Bbb F_{23})}\cdot

%\frac {29}{\#E(\Bbb F_{29})}\cdot

%\frac {31}{\#E(\Bbb F_{31})}\cdot

\;\dots

\\

&=

\frac{3}{4}\cdot

\frac{5}{8}\cdot

\frac{7}{8}\cdot

\frac{11}{12}\cdot

\frac{13}{8}\cdot

\frac{17}{16}\cdot

\frac{19}{20}\cdot

\frac{23}{24}\cdot

\frac{29}{40}\cdot

\frac{31}{32}\cdot

\frac{37}{40}\cdot

\frac{41}{32}\cdot

\frac{43}{44}\cdot

\frac{47}{48}\cdot

\frac{53}{40}\cdot

\frac{59}{60}\cdot

\frac{61}{72}\cdot

%\frac{67}{68}\cdot

%\frac{71}{72}\cdot

%\frac{73}{80}\cdot

%\frac{79}{80}\cdot

\;\dots

\\

&\overset !=\frac{1\cdot2\varpi\cdot 1\cdot 2}{4^2}

=

\bbox[lightyellow]{\frac{\varpi}4}

\approx0.65551438857302995261620989747277985342068\dots\ .

\end{aligned}

$$(The prime number two is "somehow different" in the context, the curve $E$ "degenerates" modulo two, and it turns out that there is "no" $2$-$L$-series factor.) For short, the broken arithmetic information is recollected in an expression featuring two "analytic pieces", the period $\Omega=2\varpi$, and the regulator $\operatorname{Reg}(E)=1$, together with some "global arithmetic information", which finally produces the factor $\frac 2{4^2}$. (The $4$ is the number of torsion points.)

In my eyes, this connection of an elliptic integral with the (real) period of an elliptic curve, is the most intricate and intriguing instance of a transcendent number in a situation governed by an algebraic situation.

The above $\overset!=$ is an equality, it is a theorem.

But we have no similar information for the "cousin" elliptic curve $y^2=x^3-226x$ with real period $\int_{\sqrt{226}}^\infty\frac{dx}{x^3-226x}=\bbox[lightyellow]{\frac{\varpi}{\sqrt[4]{226}}}$. Of course, the complication is on the arithmetic side, this is an elliptic curve over $\Bbb Q$ with two torsion points, $O=\infty$ and $(0,0)$, rank three, generators of the free part of $E(\Bbb Q)$ being $(-1,15)$, $(-8,36)$, $(121/4, 1155/8)$, and regulator $\operatorname{Reg}(E)\approx 23.6131617974\dots$ computed from them. Then any progress in showing the B-SD relation:

$$

\small

\frac{L'''(E,1)}{3!}

\overset?

=

\frac 1{2^2}\cdot1\cdot\frac{2\varpi}{\sqrt[4]{226}}\cdot \operatorname{Reg}(E)\cdot(226^2)

$$

would be a true breakthrough. I have to stop here.

$y^2=x^3-x$" />

$y^2=x^3-x$" />

$$1+\frac 1{1\cdot 3}+\frac 1{1\cdot 3\cdot 5}+\frac 1{1\cdot 3\cdot 5\cdot 7} +\frac 1{1\cdot 3\cdot 5\cdot 7\cdot 9}+$$ $$\frac{1}{1+\frac 1{1+\frac 2{\frac{1+ 3}{1+\frac 4{1+\dots}}}}}=\sqrt{\frac{\pi e}2}.$$

– Alex Ravsky Jan 08 '25 at 05:46