The fact that $$1^2 + 2^2 + \cdots + n^2 = \frac{n(n+1)(2n+1)}{6}$$ can be proven by a straightforward application of mathematical induction involving grinding through a bit of basic high school algebra. But although such a proof does of course suffice to establish that the result is true, it is—like so many proofs by induction—of little value in illuminating why the result is true. And it certainly does not deserve a place in “The Book” of Paul Erdős.

There is also a proof in terms of a telescoping sum, but it too offers little insight into what’s going on.

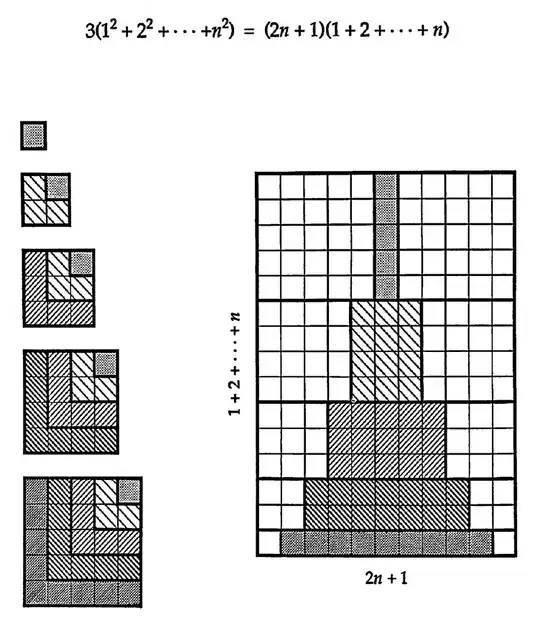

For such insights, one often turns to combinatorial proofs by double counting or to geometric proofs that provide clear visual understanding. Does either exist in this case?

As for the combinatorial technique—what Ed Scheinerman calls Jeopardy! proofs because one is given the answer(s) and must generate the question—I can cook up a scenario where an unattached man is entertaining $n$ male-female couples, and each person present can choose one of the couples (for example, the couple they think to be the happiest) and one of the men (for example, the one they think to be the wittiest). But that feels like a real stretch, and besides, why on Earth would I want to divide the number of such person-couple-man combinations by 6?

And as for a geometric proof, I can see $n$ squares in the plane strung along the line $y=x$, thus $$[0,1]\times[0,1],\; [1,3]\times[1,3],\; \ldots,\; \left[\frac{n(n-1)}{2}, \frac{n(n+1)}{2}\right]\times \left[\frac{n(n-1)}{2}, \frac{n(n+1)}{2}\right],$$ and considering their total area. But here too I see nothing naturally six about this picture that would induce me to replicate this string-of-squares drawing five more times. Nor do I see any other way to arrange the squares in the plane that’s general enough for all $n\in{\textbf N}^+$. And besides, the right-hand side of the equation is cubic in $n$, so it would seem to call for a picture in ${\textbf R}^3$ rather than ${\textbf R}^2$.