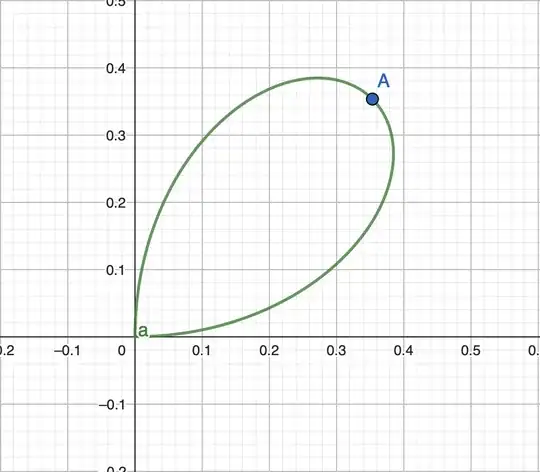

Let $\gamma:\left[0, \frac\pi2\right] \to \mathbb{R^2}$ be a curve defined by $\gamma(\theta) = (\cos^2(\theta) \sin(\theta) , \cos(\theta) \sin^2(\theta))$.

The following is the image of $\gamma$:

where I have labeled $A=\left(\frac{\sqrt2}{4},\frac{\sqrt2}{4}\right)=\gamma\left(\frac{\pi}{4}\right).$

where I have labeled $A=\left(\frac{\sqrt2}{4},\frac{\sqrt2}{4}\right)=\gamma\left(\frac{\pi}{4}\right).$

Since I am not confident with the English words used for this mathematical object, let me clarify that we call flux of $F$ through $S$ in the direction of the unit vector $n$ the integral $\int_S (F\cdot n)d\sigma$, where $$\int_S f d\sigma \stackrel{\Delta}{=} \iint_D f(\phi(u,v)) \|\phi_u(u,v) \times \phi_v(u,v)\| du dv.$$ If $S$ encloses a (bounded) region of the space, we say that the flux points inwards or outwards $S$ depending on whether the normal unit vector points towards the region enclosed by $S$ or not.

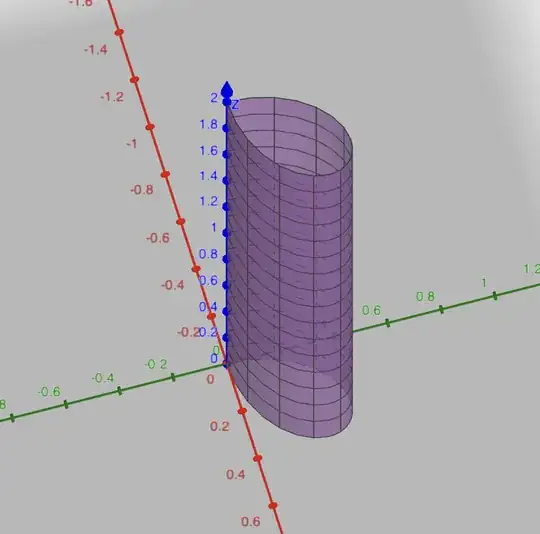

An example in an Italian book that I am studying (by N. Fusco - P. Marcellini - C. Sbordone) evaluates the inward flux of $F(x,y,z)=\left(\sqrt{x^2+y^2},0,z^2\right)$ through the lateral surface of the "cylinder" $S$ whose base is the region enclosed by $\gamma$, height is $2$ and is placed in $H=\{(x,y,z) \in \mathbb{R^3}: z \geq 0\}$.

First, we define $\phi: \left[0, \frac\pi2\right] \times \left[0, 2\right] \to \mathbb{R^3}$ such that $\phi(u,v) = (\cos^2(u) \sin(u) , \cos(u) \sin^2(u), v)$ and find that $\phi_u(u,v) = (\cos^3(u) - 2 \sin^2(u) \cos(u), 2 \sin(u)\cos^2(u) - \sin^3(u), 0)$ and $\phi_v(u,v) = (0,0,1)$. Therefore $\phi_u(u,v) \times \phi_v(u,v) = (2 \sin(u) \cos^2(u) - \sin^3(u), -\cos^3(u) + 2 \sin^2(u)\cos(u), 0).$

Then, the authors of my book observe that the normal vector to the surface in the points $\left(\frac{\pi}{4},v\right)$ is $N(u,v) = \phi_u\left(\frac{\pi}{4},v\right) \times \phi_v\left(\frac{\pi}{4},v\right) = \left(\frac{\sqrt2}{4},\frac{\sqrt2}{4} , 0\right) \implies \hat n(u,v) = \left(\frac{\sqrt2}{2},\frac{\sqrt2}{2} , 0\right)$ and claim that therefore the normal unit vector points outwards $S$, so that the desired flux is actually $\int_S (F\cdot (-\hat n))d\sigma$.

I do not understand how to establish whether the normal unit vector points towards inside or outside $S$. I am not sure if the authors' claim was based on some facts which currently I am unable to get or rather on the picture of the cylinder. If this is the case, I would appreciate a detailed explanation on why the drawing is enough to deduce the direction of the normal unit vector.

However, I wonder how one would deal with a more difficult curve $\gamma$: suppose you cannot draw it. How would you figure out whether the normal unit vector points inwards or outwards?