We are given a multinomial distribution with $k$ bins and $n$ balls. The number of balls is at most the number of bins, i.e., $\sqrt{k} \le n \le k$. The probabilities of throwing a ball into a speficic bin are monotone non-increasing, i.e. $p_1 \ge p_2 \ge \dots \ge p_k$, but we can also assume they are all equal ($p_1 = p_2 = \dots = p_k$). Let $X_i$ be the random variable representing the number of balls in bin number $i$. Let $X = \max\{X_1, \dots, X_k\}$, and let $Y = \left|\{i \in [k] : X_i = X\}\right|$. Are there any known upper bounds to $\mathbb{E}[Y]$?

Attempt. It's easy to see that, by the Birthday paradox, $\mathbb{E}[Y] = \Theta(\sqrt{k})$ when $n = \Theta(\sqrt{k})$. Also the case $n \ge k \cdot \text{polylog}(k)$ is doable. I did not succeed in other cases so far. I found the paper about balls into bins where there are bounds to the expectation of the number of bins whose ball count surpasses a certain threshold, but this is deeply different from what I am looking for.

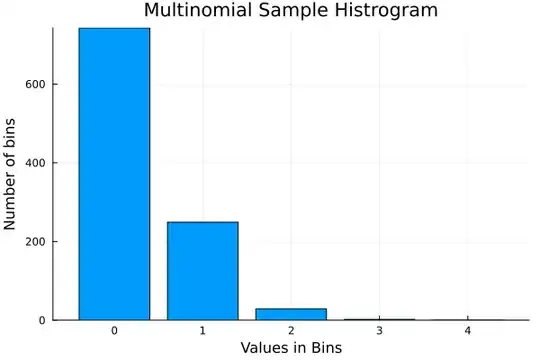

Interestingly, in experiments it seems there are always very few bins with the maximum number of balls, both for the case $n = k \log_2 k$ (first figure) and the case $n = \sqrt{k} \log_2(k)$ (second figure).

In the above figure I have set $k = 2^{10}$ and $n = k \log_2(k)$.

In the above figure I have set $k = 2^{10}$ and $n = \sqrt{k} \log_2(k)$.

Instead, when $n = \Theta(\sqrt{k})$, by the Birthday paradox you have that with constant probabilities the birthdays fall in $n$ different days, hence the answer is $\Theta(\sqrt{k})$.

– CuriousGuy Dec 09 '24 at 10:08