I am trying to understand the proof behind why the Moment Generating Function (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moment-generating_function) of a random variable is is unique.

For example, consider the following case of two random variables $X$ and $Y$, i.e both random variables are in terms of $x$, e.g. $x = f(x)$, $y = g(x)$:

$$ \text{PDF of } X: \quad f(x) $$

$$ \text{PDF of } Y: \quad f(y) $$

$$ M_X(t) = \mathbb{E}[e^{tX}] = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} e^{tx} f(x) \, dx $$

$$ M_Y(t) = \mathbb{E}[e^{tY}] = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} e^{ty} f(y) \, dx $$

From here, define a function that is the difference between both PDF's : $d(x) = f(x) - f(y)$

Using this, we can also define a function which is the difference between both MGF's:

$$ Z = M_X(t) - M_Y(t) = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} e^{tx} f(x) \, dx - \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} e^{ty} f(y) \, dy $$

$$ = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \left [ e^{tx} f(x) - e^{ty} f(y) \right ] \, dx $$

$$ = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} e^{tx} \left[ f(x) - f(y) \right ] \, dx $$

$$ = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} e^{tx} \, d(x) \, dx $$

Now, consider the following:

$$ \text{Case 1:} \quad d(x) = f(x) - f(y) = c_1 \quad \text{where} \quad c_1 > 0 \quad \text{and} \quad c_1 \neq 0 $$

$$ \text{Case 2:} \quad d(x) = f(x) - f(y) = c_2 \quad \text{where} \quad c_2 > 0 \quad \text{and} \quad c_2 \neq 0 $$

The implications of both cases are:

$$ \text{Case 1:} \quad Z = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} e^{tx} c_1 dx = z_1 $$

$$ \text{Case 2:} \quad Z = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} e^{tx} c_2 dx = z_2 $$

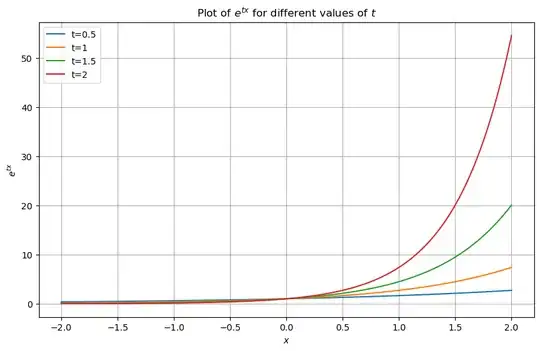

Now, when we look at the graph for $e^{tx}$, we can see that when $t>0$, the function is always positive and increasing (monotonic):

This means that the integral of $e^{tx}$ by itself must always be greater than $0$.

This is where I use proof by contradiction:

- Let's suppose that Case 1 is $0$, i.e. $z_1 = 0$

- If Case 1 is $0$, this means that Case 2 $\neq 0$.

- This is because the function $e^{tx}$ is always increasing by itself, and case 2 is pushing the function further than case 1

Thus, if we need $Z$ (difference between two MGFs) to always be $0$, then $f(x)$ always has to be equal to $f(y)$ - implying the uniqueness of MGFs.

Is my proof correct?

# plot 1

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

x = np.linspace(-2, 2, 400)

t_values = [0.5, 1, 1.5, 2]

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

for t in t_values:

y = np.exp(t * x)

plt.plot(x, y, label=f't={t}')

plt.title('Plot of $e^{tx}$ for different values of $t$')

plt.xlabel('$x$')

plt.ylabel('$e^{tx}$')

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True)

plt.show()

plot 2

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

x = np.linspace(-2, 2, 400)

t = 1

c_values = [0.5, 1, 1.5, 2]

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

for c in c_values:

y = c * np.exp(t * x)

plt.plot(x, y, label=f'c={c}')

plt.title('Plot of $c \cdot e^{tx}$ for different values of $c$ with $t$ fixed')

plt.xlabel('$x$')

plt.ylabel('$c \cdot e^{tx}$')

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True)

plt.show()

#plot 3

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.integrate import quad

x = np.linspace(0, 2, 400)

t = 1

c_values = [0.5, 1, 1.5, 2]

def integrand(x, c, t):

return c * np.exp(t * x)

cumulative_integrals = np.zeros_like(x)

for c in c_values:

integral_values = [quad(integrand, 0, xi, args=(c, t))[0] for xi in x]

cumulative_integrals += integral_values

plt.fill_between(x, cumulative_integrals - integral_values, cumulative_integrals, label=f'c={c}')

plt.title('Cumulative Integrals of $c \cdot e^{tx}$ from 0 to 2 for different values of $c$ with $t$ fixed')

plt.xlabel('$x$')

plt.ylabel('Cumulative Integral Value')

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True)

plt.show()