I think that this explanation of Stephen Cole Kleene, Mathematical Logic (1967 - Dover reprint) [pag.10 - footnote 12] is a good short elucidation of the "formalization" of conditional in a truth-functional setting :

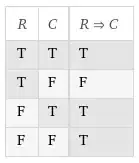

The ordinary usage certainly requires that "If A, then B" to be true when A and B are both true, and to be false when A is true but B is false. So only our choice for T in the third and fourth lines [of the truth-table entered for A and B, i.e. the lines F-T and F-F] can be questioned. But if we changed T to F in both these lines, we would simply get a synonym for ∧ ["and"]; in the third line only, for ↔ [i.e. the bi-conditional]. If we changed T to F in the fourth line only, we would loose the useful property of our implication that "If A, then B" and "If not B, then not A" are true under the same circumstances [...].

The truth-functional definition of propositional connectives is a "model" that in some cases "fit" quite well with our usage in natural language (negation, disjunction, conjunction) and not so well in other cases (conditional).

When we assert a sentence A we are expressing the fact that we "judge it" to be true.

Thus, asserting the conditional A → B means to "judge" it true.

When mathematicians (like Frege) introduced the truth-functional conncetive , they have in mind one characteristic property of the connective, viz., the rule of modus ponens. With this rule, we assert A → B and A; in this case, the first assertion "exclude" the case when A is true and B false, while the second assertion "exclude" the two cases where A is false.

Thus, we have only one possibility left : B true, and this is what we expected.

In our "ordinary" use of the language we seldom assert a conditional "if ..., then ___" when we know the antecedent to be false; but the "modelling" of mathematical logic fit quite well with the use in ordinary mathematics.

The very important "context" in mathematics is the following :

Σ⊨φ;

in this case we say that Σ entails φ. The condition validating the relation of "entailment" is that : every interpretation that satisfy (all the sentences in) Σ will also satisfy φ; or, equivalently, there is no interpretation such that all of Σ are true and φ is false.

This "context" is commonly used when we assert that some thorem (φ) follows from a set Σ of sentences, e.g.the axioms of a theory.

When Σ={σ}, from σ⊨φ we have that : ⊨σ→φ.

This result establish a strict connextion between the conditional (→) and the relation of entailments (⊨). The two are different relations, but the above link between them is so useful that we "accept" the "not perfect" fit of the conditional with our natural language habits.

The origin dates from Ancient Greece, with Stoics logic.

The modern view is due to Peirce and Frege.