Let $\Omega\subseteq \mathbb R^n$ be an open, bounded, connected set with a $C^\infty$ boundary. For an application in a project I'm working on, I need a function $f : \bar\Omega\to\mathbb R_{\ge 0}$ with the following properties :

- $|f(x)|\le M$ for all $x\in\bar\Omega$ and some $M>0$, i.e. $f$ is bounded

- $f(x)=0\iff x\in\partial\Omega$

- $f$ has a closed form expression

- $f\in C^\infty(\bar\Omega)$

In words, I'm looking for a bounded, smooth function which is positive in $\Omega$ and vanishes on $\partial\Omega$. The third item is here because I would like to implement the function and compute with it, so I can't have something like the limit of functions defined on increasing subsets of $\Omega$ or something like $f=\sum 2^{-n}f_n(x)$.

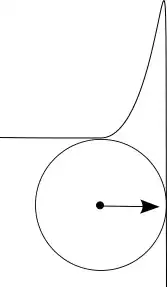

With all these taken into account, the most natural function which came to my mind is $$f:x\mapsto \begin{cases} &\exp\left(-\frac{1}{d(x,\partial\Omega)^2}\right) \ \ &\text{ if } x\in\Omega\\ &0 &\text{ if } x\in\partial\Omega\end{cases}, $$ where $d(x,\partial\Omega) := \min_{y\in\partial\Omega}\|x-y\| $ is the Euclidean distance between $x$ and $\partial\Omega$. Basically, $f$ is just an analogue of the classical bump function, but "engineered" to have the properties that I need. It is indeed clear that the first three items are satisfied by my $f$, but unfortunately the fourth item is not clear at all : $d$ is a priori not $C^\infty$ (it is only Lipschitz continuous), so we can't apply the chain rule.

My question is thus the following : How to show that $f$ is $C^\infty$ ? If $f$ is not $C^\infty$, do you know of any other function which satisfies the four stated requirements ?

Thanks for your time !

My attempts : The only proof I'm aware of to show smoothness of bump functions consists in showing that derivatives of all orders exist and converge to the correct value on $\partial\Omega$. The problem however is that $d(\cdot,\partial\Omega)$ is only Lipschitz continuous, and (I'm pretty sure) not differentiable on $\partial\Omega$, so besides (weak) derivatives of first order, $d(\cdot,\partial\Omega)$ is not guaranteed to have any derivatives of higher order and so it's hard to make sense of $f^k$, let alone study its convergence when $x\to \partial\Omega$.

An idea I had was to work locally : although $\partial\Omega$ is not convex, I am hoping that for "almost" each $x\in\Omega$, there should be a locally defined "projection map" $P_x : \Omega\supseteq U_x \to \partial\Omega$ with the same regularity as $\partial\Omega$ such that $d(y,\partial\Omega) = \|y-P_x(y)\|$ for all $y\in U_x$. If such a map $P_x$ exists, then I think I can work locally and apply the chain rule. I've seen results in this direction in the literature, but never quite the result I want, so I'm not sure if it is actually true...

Another idea I had was to approximate $f$ by a sequence $(f_n)$ of $C_c^\infty(\Omega) $ functions, and show that the derivatives of $(f_n)$ converge to the (weak ? distributional ?) derivatives of $f$ in $L^\infty$, which would give me the result I want. The problem is that I have absolutely no clue on how I would go about bounding $\|\partial^\alpha f_n -\partial^\alpha f\|_{L^\infty} $ in terms of something I can control.