Draw $n$ random chords in a circle, where each chord connects two independent uniformly random points on the circle.

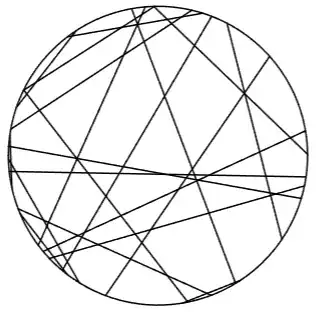

Here is an example with $n=20$:

In this example, there are $49$ polygons (I only consider the polygons with no chords going through them): $24$ triangles, $14$ quadrilaterals, $7$ pentagons, $4$ hexagons.

What is the limiting distribution of the kinds of polygons, as $n\to\infty$?

I made a random chord generator.

The average number of sides is $4$.

We can show that the average number of sides of the polygons is $4$, by the following argument.

Let $I=$ number of intersections, $G=$ number of polygons.

- $\mathbb{E}(I)$ is the number of pairs of chords times the probability that two chords intersect, so $\mathbb{E}(I)=\frac16n(n-1)$.

- This answer shows that the number of regions (including regions with curved edge) is $1+I+n$. Now $G$ dominates the number of regions with curved edge, so we can ignore the regions with curved edge. So $\frac{I}{G}\to 1$ as $n\to\infty$.

- Each intersection is a shared vertex of $4$ polygons, so each one of those polygons "gets" $\frac14$ of that intersection. So each polygon should have on average $4$ vertices.

One elegant distribution that gives an average of $4$ would be: $\frac12$ triangles, $\frac14$ quadrilaterals, $\frac18$ pentagons, $\frac{1}{16}$ hexagons, etc. because $\sum\limits_{n=3}^\infty \frac{n}{2^{n-2}}=4$. I wonder if that distribution is the answer.

This question was inspired by the question, "On average, how many times must a circular pizza be randomly cut, to get a piece with no curved edge?"

I suspect that this doesn't work; however, if it does, then instead of chopping up the circle into finer and finer pieces, you can take larger and larger circles. In the limit, you should end up with a distribution of lines in the plane, which will likely have more useful symmetries than the original circle problem.

– Greg Muller Oct 23 '24 at 13:36