Since my conditional average is different, or very possibly i misunderstood the question, here is a first (partial) answer that numerically searches for a value. We model, write a formula for the mean perimeter $p$, and evaluate numerically. The result is more than four, so there must be a mismatch in the modelling.

Let $\odot$ be the unit circle. For a point $P$ on $\odot$ let $\theta(P)$ be the number in $[0,2\pi)$ with $P=\exp i\theta(P)$. Let now $A,A';B,B';C,C'$ be three pairs of (independent) points in $\odot^6$. Then we want to compute the number, a conditional probability w.r.t the event $E$ below:

$$

p = \Bbb E\Bigg[\ AA'+BB'+CC'\ \Bigg|\ \underbrace{2\max(AA',BB',CC')\le AA'+BB'+CC'}_{=E}\ \Bigg]\ .

$$

Since there is an obvious rotational symmetry, we may and do assume that the points $A',B',C'$ are all equal to $\exp i0=1$. Denote this reference point by $R=1$. Exactly one of the sides $AA', BB',CC'$ is maximal with positive probability. Then $E$ splits as $E_A\cup E_B\cup E_C$, where $E_A$ the portion where $AA'$ is maximal, and we similarly introduce notations $E_B$ and $E_C$.

Then by symmetry we may restrict to the $E_A$ piece,

$$

p=

3\Bbb E\Bigg[\ AA'+BB'+CC'\ \Bigg|\ \underbrace{BB',\;CC'\le AA' \text{ and }AA'\le BB'+CC'}_{=E_A}\ \Bigg]\ .

$$

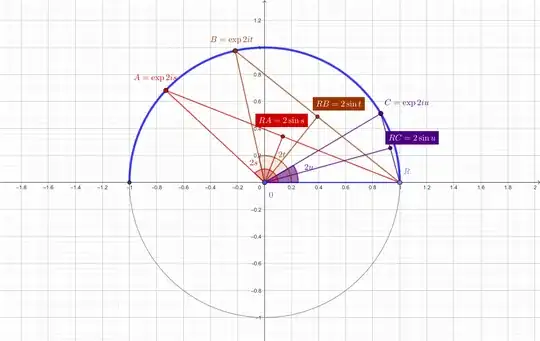

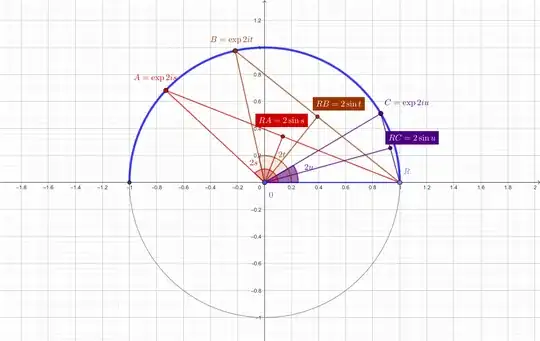

We use now the following model $\Omega$ for the probabaility space. The point $A$ is of the shape $\exp 2is$ with $s\in[0,2\pi]$. But points reflected w.r.t. the $Ox$-axis have the same distance, so by symmetry we may and do assume that $s\in [0,\pi]$. In the same manner, we parametrize $B,C$ as $\exp 2it$ and $\exp 2 iu$. The segments $AA'=RA$, $BB'=RB$, $CC'=RC$ are then respectively $2\sin s$, $2\sin t$, $2\sin u$. There is one more symmetry we can use to make later computations simpler. One of $t,u$ is smaller, we assume $0\le u\le t$.

$$

\begin{aligned}

\Omega &= \{\ (s,t,u)\in[0,\pi/2]^3\ |\ 0\le u\le t\le s\le \pi/2\ \}\ ,\\

E_A &=\{\ (s,t,u)\in[0,\pi/2]^3\ |\ 0\le u\le t\le s\ ,\ \sin s\le \sin u+\sin t\ \}\ .

\end{aligned}

$$

A picture for $A,B,C$:

The measure on $\Omega$ is (a normed version of) $ds\; dt\; du$, which corresponds to taking $A,B,C$ uniformly on the radar. We consider the function

$$

f(s,t,u)=2(\sin s+\sin t+\sin u)\ ,

$$

and the probability to be computed is:

$$

p=\frac

{\displaystyle \iiint_{E_A}f(s,t,u)\; ds\;dt\; du}

{\displaystyle \iiint_{E_A}1\; ds\;dt\; du}

\ .

$$

We change variables, use $x,y,z\in[0,1]$ for $\sin s,\sin t,\sin u$. Then $s=\arcsin x$, $ds=dx/\sqrt{1-x^2}$, and similar for $dt,du$.

So we have to compute on the region $D\subset [0,1]^3$ given by

$0\le z\le y\le x\le\min(1,y+z)$ the following:

$$

p=

\frac

{\displaystyle \iiint_D 2(x+y+z)\;

\frac{dx}{\sqrt{1-x^2}}\;

\frac{dy}{\sqrt{1-y^2}}\;

\frac{dz}{\sqrt{1-z^2}}

}

{\displaystyle \iiint_D

\frac{dx}{\sqrt{1-x^2}}\;

\frac{dy}{\sqrt{1-y^2}}\;

\frac{dz}{\sqrt{1-z^2}}

}

\ .

$$

Wolfram alpha delivers the values

The quotient is roughly $13/3$, a number bigger four...

Let $(x,y,z)$ be in $D$. So $x\in[0,1]$. Because of $x\le y+z\le y+y=2y$, $y$ ranges between $x/2$ and $x$. Then $z$ is constrained to run betweeen $x-y$ and $y$. We can integrate w.r.t. $z$, and obtain a possibly simpler formula:

$$

p=

\frac

{\displaystyle \int_0^1

\frac{dx}{\sqrt{1-x^2}}

\int_{x/2}^x\frac{dy}{\sqrt{1-y^2}}

\begin{pmatrix}

2(x+y)(\arcsin x-\arcsin(x-y)

\\

+2\left( \sqrt{1- (x-y)^2}-\sqrt{1-y^2}\right)

\end{pmatrix}

}

{\displaystyle \int_0^1

\frac{dx}{\sqrt{1-x^2}}

\int_{x/2}^x\frac{dy}{\sqrt{1-y^2}}

(\arcsin x-\arcsin(x-y))}\ .

$$

We can integrate w.r.t. $z\in[y-x,y]$ first. Then w.r.t. $y\in[x/2,x]$.

And finally w.r.t. $x\in [0,1]$. Then pari/gp confirms the above results:

? intnum(x=0,1, intnum(y=x/2, x, 1/sqrt(1-x^2)/sqrt(1-y^2) * (asin(y) - asin(x-y))))

%10 = 0.41262741938920412841487820893180718042

? {intnum(x=0,1, intnum(y=x/2, x, 1/sqrt(1-x^2)/sqrt(1-y^2) *

( 2(x+y)(asin(y) - asin(x-y)) + 2*(-sqrt(1-y^2) + sqrt(1 - (x-y)^2)) )))}

%11 = 1.7875657866180001900026538928071722581

? %11 / %10

%12 = 4.3321546330199344360575654063388233913

I have to submit, and come back with an edit (or delete) if i misunderstood completely the situation.