Why the derivatives $f^{(n)}(x)$ of Flat functions grows so fast? (intuition behind)

In this other question I did about Bump functions, other user told in an answer that these kind of functions "tends aggressively fast to zero at the limits of the support", and it keeps in my mind trying to understand what this is supposedly means:

From one side, the functions speed, acceleration, and any other derivatives are bounded since these functions are smooth $C_{c}^{\infty}$, which implies that is completely the opposite was being proposed, the speed and acceleration is finite as any other derivatives, and they looks being well-behaved functions as you expect for something smooth (at least for me, since I relate smooth with polynomials).

But on the other hand, this user and his answer has a point: I have noticed that as I take increasing order derivatives of Flat functions like Bump functions, their higher derivatives maximum values start increasing very fast $\|f^{(n)}(x)\|_{\infty}$ as $n$ grows, and as I understood the formulas, I don't get the intuition behind it.

For me its very counter-intuitive that something that is becoming a constant with bounded speed ($\|f^{(1)}(x)\|_{\infty} \ll \infty$) somehow have higher derivatives are kind of blowing up, which is even more weird in the case of Bump functions since they are smooth $C_{c}^{\infty}$. And with becoming a constant, I mean that for continuously becoming flat all the derivatives must becomes zero at these special inflection points $x^*$ since $\frac{d^n}{dx^n}f(x)\Biggr|_{x\to {x^*}^{\pm}}=0,\,n\geq 1,\, n\in \mathbb{Z}$.

As example, for polynomials as I increase the order of their derivatives, they start to approach to a straight line as their constituent polynomial reduce is order (at least until you match the order of the polynomial), but instead in Flat functions they start to blowing up similarly to what happens when taking $n^{th}$-differences among samples of a Brownian motion, which are in converse very irregular nowhere-differentiable continuous functions (they are actually example of pathological functions, but also as are Flat functions since they aren't analytical in their full domains - check Non-analytic smooth function).

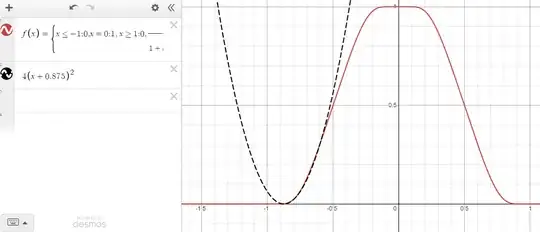

To use a simple example as common ground for the answers let think of this one:

$$f(x) = \begin{cases} 0,\quad x\leq -1;\\

0,\quad x\geq 1;\\

1,\quad x=0;\\

\dfrac{1}{1+\exp\left(\frac{1-2|x|}{x^2-|x|}\right)},\quad\text{otherwise;}

\end{cases}$$

You can check the plot of $f(x)$ in Desmos.

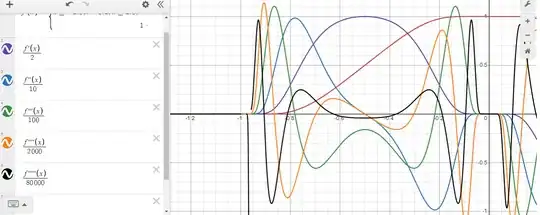

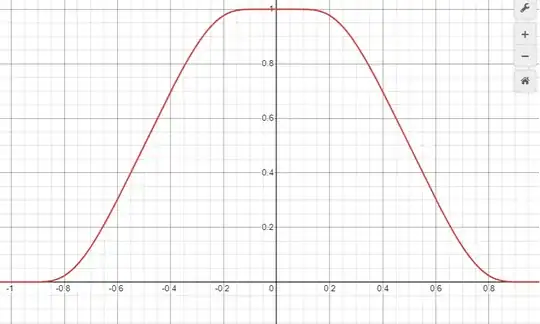

Their first derivatives' uniform norms are: $$\|f(x)\|_{\infty} = 1;\quad \|f'(x)\|_{\infty} = 2;\quad \|f''(x)\|_{\infty} \approx 9.84;\quad \|f^{(3)}(x)\|_{\infty} \approx 110.56;\quad \|f^{(4)}(x)\|_{\infty} \approx 2,280.4$$ As you could check in Desmos. As you could see they grow very fast, I tried to make a plot $n\,\text{vs}\|f^{(n)}\|_{\infty}$ and its becomes somehow linear only when applying $\ln(1+\ln(1+\|f^{(n)}\|_{\infty}))$ so I think it grows even greater than exponential, all this even when, at least visually, they look quite smooth and even comparable with a traditional quadratic decay (plot), so behaving as normal as traditional polynomials do:

So I would like to know What is actually happening here on this specific points the functions become flat, since I have arguments, I think, opposite from each other being true both at the same time, so I hope you could help me un improve my intuition about this situation.

PS: I use a lot of non-accurate meanings of some terms which I have indicated with italics, this as I am trying to improve the intuition behind and not just a formal formulation. I hope you answers also could focus in the intuition (that why I used the soft-question tag), but also formal demonstration are welcomed: my knowledge in modern abstract math is very limited (for not saying null), so please try to kept the answers at a level of undergraduate engineering courses if possible. Thanks you beforehand.

Added later

After the comment by @MartinR, I checked where the peaks of the higher order derivatives are located (I scaled them in order to be comparable) Desmos, and they start to approach the points when the flat function became zero, so there is almost no amplitude there and the slope is even lower than the slope of the function $y(x)=x$:

Since the speed is almost zero there, I am tempted to say that the situation is more like a mathematical artifact than saying "tends aggressively fast to zero" near the flat points, which could be seen because $f'(x) \approx 0$ near that neighborhood: Would you agree with that? Or are there some important technical thing I am missing with this interpretation?

I understand the rate of growth of $f(x)$ when rising from zero is nice since $\|f′(x)\|_{\infty}$ is low, but for these almost zero values near flat points, I am not sure if somehow $f(x)$ is growing faster that what any line polynomial of order $n\geq 2$ could achieve on such a short distance, but not meaning is fast as speed since just $y(x)=|x+x^*|$ rises faster than $f(x)|_{x\to x^*}$ at flat point $x^*$ (but I believe this intuition is also wrong, since each derivative peak happen at different points). Hope you could explain it.

2nd update

After the answer by @LorenzoPompili looks I have a confusion about the growth rate and the decay rate (which I haven't solve yet).

Which is clear to me is that the rise from zero is not infinitely fast since $f'(x)$ is quite low always.

But about the decay rate I don't know if I am "confusing the map with the territory": I am trying to understand if there is a true aggressive decay, of instead, the power series (analytical) description have limitations that don't allow to properly describe this kind of functions, don't meaning these flat function by itself are aggressively fast.

In simple words: or they have indeed aggressive decay, or instead a power series is behaving like a long wood stick that cannot match some curvy figure, if I pressed it too much, it would broke, or instead it would detach from other points they have to also fit but far away from where I am applying pressure (think of making a wooden boat).

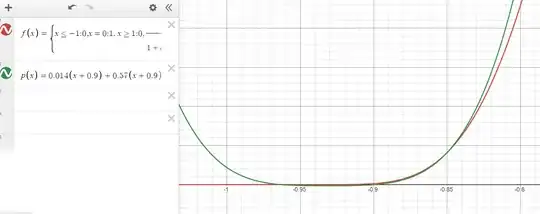

I am inclined to believe in the "wood" idea, because if I compare the function $f(x)$ near the first flat point $x^*=-1$ with the following polynomial: $$p(x) = 0.014(x+0.9)+0.57(x+0.9)^2+11.3(x+0.9)^3+91.8(x+0.9)^4$$ which is a modified version of a Taylor series at $x=0.9$. As it could be seen in Desmos it decays faster than $f(x)$ since start above it (this from right to left), matches the function $f(x)$, and then becomes zero before $f(x)$.

So in this sense a polynomial decays faster (nothing weird so far). Other story is that a power series would not be able to match perfectly the function since it would struggle in becoming flat: from one point of view is acting the Identity Theorem against it, while in the other hand the Stone–Weierstrass theorem tells I could use a polynomial as close as required to approximate it.

So I don't know which one is going to win: the first one says its imposible to match so is defending the point of view of aggressive decay, but the second one tells you that a polynomial decay would always be able to match it as close as desire, on line with the polynomial $p(x)$ comparison.

Now, I could make a truly aggressive decay by introducing a constant $n\geq 1$ on $f(x)$ as: $$f_n(x) = \begin{cases} 0,\quad x\leq -1;\\ 0,\quad x\geq 1;\\ 1,\quad x=0;\\ \dfrac{1}{1+\exp\left(\dfrac{n(1-2|x|)}{x^2-|x|}\right)},\quad\text{otherwise;} \end{cases}$$

Which behaves as a smooth approximation of the Rectangular function as $n\to\infty$. Checking the previous plot with the higher derivatives scaled new Desmos, while I increase the value of $n$ the higher derivative's peaks start moving from the flat point to where the slope is increasing near $x=\frac12$, but I am not sure if it means that the flat point is becoming irrelevant (somehow supporting the "wood" argument), or if instead it is moving into the point $x=\frac12$ where now it is kind-of rising from zero.

As you could see I still trying to understand, @LorenzoPompili gave an amazing answer but I am still lost on the details, while I think the "wood" argument is what stands, I do hope the aggressive decays is what is really happening (I think the last one is what @LorenzoPompili is telling me, from what I am understanding so far), since having that kind of restriction for rising from a position of flatness could be a good argument for dismissing self-rising solutions, like the one that happen on the Norton's Dome example, like there is an infinite inertia against start moving from zero just by itself. If there really is a connection, please try to elaborate into it.