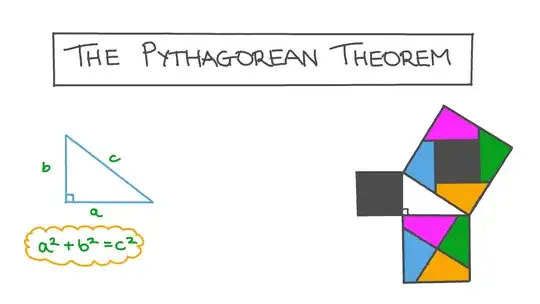

We all know $a^2 + b^2 = c^2$ on a right angle triangle. Yes. It works. It can be proven using area of square and everything. But my question is: why?

What makes the number 2 so special, that it defines the 2-norm, gets involved everywhere in vector space, and even statistics when we talk about independent random variables are almost like perpendicular vectors and their variance can simply. (The last part might be a bit of a stretch on my part.)

I know this feels almost like asking why gravity is 9.8. It just is. It is not because 9.8 is a perfect number in number theory or anything. But our insistence on using the square has to come from somewhere. To me, the only natural connection of 2 or square of anything must be linked to the area of square on a flat surface. Why isn't it $a^4 + b^4 = c^4$? Is that a worse world to live in? In other words, what is the first principle reason that the square law comes out so often if the only first principle meaning is something multiply by itself?

This question comes from my long history of not understanding why statistics often use the standard deviation and not the average distance. Some people say because we want to emphasize the outliers so variance is the root cause (but why?) and some people say standard deviation has nice properties (precisely because of the 2 in the square law). In a way, I feel that it all comes down to the Pythagorean theorem. But why?

In the end, I can only comfortably establish that square is something multiplied by itself, or area of square on a flat surface. But what does length of sides on a right-angle triangle has to do with them? Any explanation other than: it just works? Why Pythagorean theorem works, that no matter the dimension, if we are interested in the distance, we still square them?

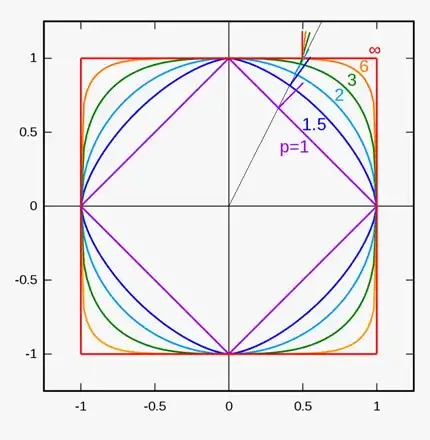

Are you suggesting the Pythagorean might work with another value in place of 2?

– Robbie Goodwin Sep 28 '24 at 19:50