Firstly, you have to ensure that $f(x)$ does not tend to $0$ as $x\to\infty$ uniformly. Because then, after a certain $M$, $f(x)<1$ for all $x\geq M$ and hence, $f(x)^{2}$ will have a faster decay and hence $\int_{M}^{\infty}f(x)^{2}\,dx\leq \int_{M}^{\infty}f(x)\,dx<\infty$. And $f$ will be uniformly bounded on $[0,M]$ and hence integrable.

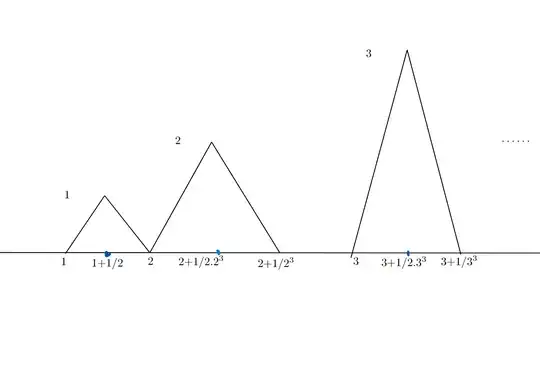

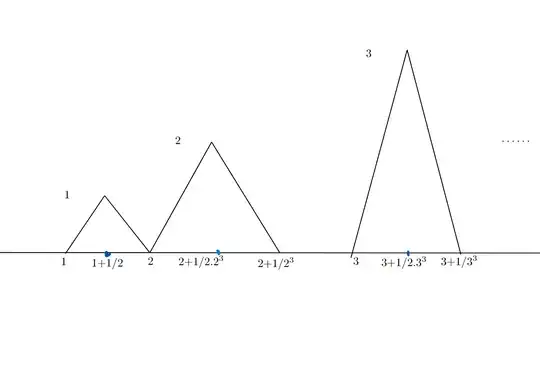

The way to construct a counter-example is by using pictures.

Let $f(x)=0$ for $x\in[0,1]$.

For $x\geq 1$, for each $n\geq 1$, in the interval $[n,n+\frac{1}{n^{3}}]$, let $f(n)=0, f(n+\frac{1}{2n^{3}})=n$ and $f(n+\frac{1}{n^{3}})=0$ and we linearly interpolate between these points. And let $f$ be $0$ elsewhere. Then $f$ is easily continuous as it is formed by linear interpolations.

(Note that the triangles may not appear symmetric. That is because I am bad at drawing).

The idea is that you are constructing triangles with unbounded heights but with fast enoguh diminishing base lenghts. The base of the triangles are formed by the interval $[n,n+\frac{1}{n^{3}}]$ and the height of the triangle is $n$, i.e. $f(n+\frac{1}{2n^{3}})=n$

So $\int_{0}^{\infty}f(x)\,dx=\sum_{n}\text{Area of the nth-triangle}=\sum_{n}\frac{1}{2}\cdot n\cdot\frac{1}{n^{3}}<\infty$

But, now note that for $x\in [n,n+\frac{1}{2n^{3}}]$, $f(x)=2\cdot(n^{4}x-n^{5})$

So \begin{align}\int_{0}^{\infty}f(x)^{2}\,dx&=\sum_{n}2\cdot \int_{n}^{n+\frac{1}{2n^{3}}}4(n^{4}x-n^{5})^{2}\,dx\\\\&=\sum_{n}\frac{8}{3n^{4}}\bigg(n^{4}(n+\frac{1}{2n^{3}})-n^{5}\bigg)^{3}\\\\&=\sum_{n}\frac{8}{3n^{4}}\cdot\left(\frac{n}{2}\right)^{3}\\\\

&=\sum_{n}\frac{1}{3n}=\infty\end{align}