This answer is very similar to the one by @JadeVanadium (+1), but with explicit Sudoku solutions and verification, replaced by constructions and argument. I think it is nice to have both.

A completed Sudoku is precisely a function $f\colon {\mathbb{F}_3}^4\to {\mathbb{F}_3}^2$ satisfying that for any $a_1,a_2,a_3,a_4\in {\mathbb{F}_3}$ the following maps are bijections:

$$

(x,y)\mapsto f(x,y,a_3,a_4),\\(x,y)\mapsto f(a_1,a_2,x,y),\\(x,y)\mapsto f(x,a_2,y,a_4).

$$

These three conditions are just the usual restrictions that rows, columns, and blocks contain distinct entries.

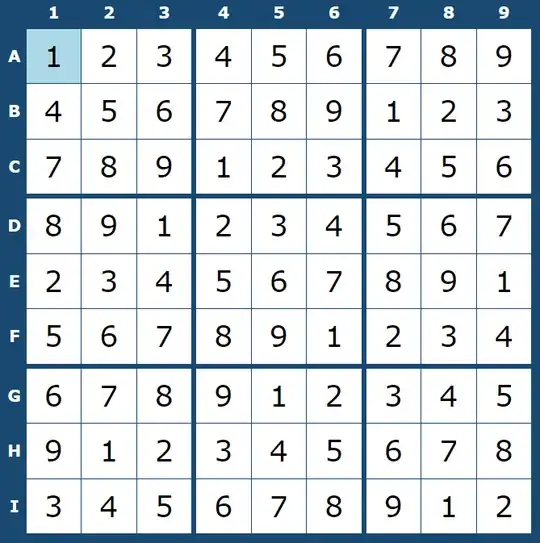

Thus one solution is $f(a_1,a_2,a_3,a_4)=(a_1+a_4,a_2+a_3)$.

This generalises to the family of solutions $f^\lhd(a_1,a_2,a_3,a_4)=(a_1+a_4,(a_1\lhd a_2)+a_3)$ where for $i\in \mathbb{F}_3$, we have $i\lhd \in S_{\mathbb{F}_3}$.

Let $C$ be the set of $54$ lines in ${\mathbb{F}_3}^4$ the form $(*,a_2,a_3,a_4)$ or $(a_1,a_2,*,a_4)$ (where the $a_i$ are fixed values). For a completed Sudoku $h$, let $N(h)$ denote the number of distinct images of elements of $C$: $$N(h)=|\{h(I)\subset {\mathbb{F}_3}^2\vert\,\, I\in C\}|.$$

Transformation 1 will relabel the images $h(I)$, but not change the number of them. We claim the remaining transformations permute the elements of $C$, so also do not effect $N(h)$:

Transformation 2 consists of maps of the form $$\qquad\,\,\,\,(a_1,a_2,a_3,a_4) \mapsto (-a_1,-a_2,a_3,a_4)\\{\rm or}\qquad (a_1,a_2,a_3,a_4) \mapsto (a_1,a_2,-a_3,-a_4) $$

These clearly preserve elements of $C$.

Transformation 3 consists of maps of the form $$\qquad\,\,\,\,(a_1,a_2,a_3,a_4) \mapsto (a_3,a_4,-a_1,-a_2)\\{\rm or}\qquad\qquad (a_1,a_2,a_3,a_4) \mapsto (-a_3,-a_4,a_1,a_2)\\{\rm or}\qquad (a_1,a_2,a_3,a_4) \mapsto (-a_1,-a_2,-a_3,-a_4)\,\,\, $$

These also preserve elements of $C$, with the first two interchanging the lines of the form $(*,a_2,a_3,a_4)$ with the lines of the form $(a_1,a_2,*,a_4)$.

Transformations 4 and 5 have the form:$$\qquad\,\,\,\,(a_1,a_2,a_3,a_4) \mapsto (a_1,\sigma(a_2),a_3,a_4)\\{\rm or}\qquad (a_1,a_2,a_3,a_4) \mapsto (a_1,a_2,a_3,\sigma(a_4)) $$

respectively, for some $\sigma\in S_{\mathbb{F}_3}$. Clearly these also preserve elements of $C$.

Transformations 6 and 7 have the form:$$\qquad\,\,\,\,(a_1,a_2,a_3,a_4) \mapsto (\sigma_{a_2}(a_1),a_2,a_3,a_4)\\{\rm or}\qquad (a_1,a_2,a_3,a_4) \mapsto (a_1,a_2,\sigma_{a_4}(a_3),a_4) $$

respectively, for $\sigma_i\in S_{\mathbb{F}_3}$ which depend on the parameter $i$. These preserve elements of $C$. Note these make a complete mess of lines of the form, $(a_1,*,a_3,a_4)$ or $(a_1,a_2,a_3,*)$, which is why we defined $C$ the way we did.

We conclude that $N$ is invariant on equivalence classes of completed Sudoku's.

Now $N(f)= 6$, as the images of elements of $C$ under $f$ are just the horizontal or vertical lines in ${\mathbb{F}_3}^2$.

It remains to find a product $ \lhd\colon \mathbb{F}_3 \times \mathbb{F_3} \to \mathbb{F_3}$ such that $N(f^\lhd)\neq 6$. Recall, the only constraint we placed on $\lhd$ in order for $f^\lhd$ to be a valid Sudoku solution was for $i\in \mathbb{F}_3$, we have $i\lhd \in S_{\mathbb{F}_3}$.

Thus $$i\lhd j = (-1)^{\delta_{0i}}j,$$ gives us a valid Sudoku solution $f^\lhd$, where $\delta$ is the usual Kronecker delta.

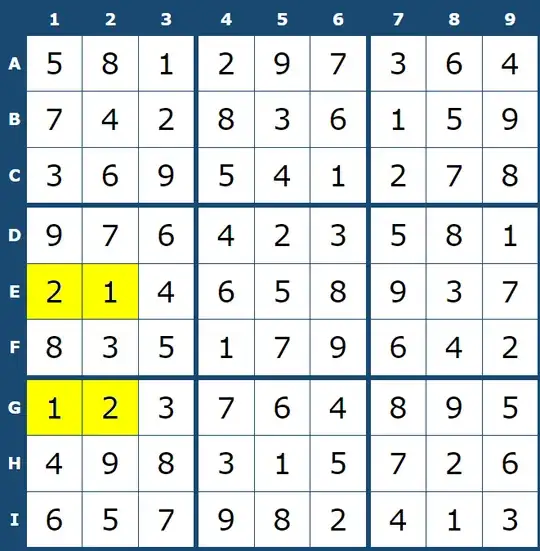

The lines $(a_1,a_2,*,a_4)$ map to the $3$ vertical lines in ${\mathbb{F}_3}^2$ just as they did under $f$. Also the lines $(*,0,a_3,a_4)$ map to the same $3$ horizontal lines as they did under $f$. However $(*,1,0,0)$ maps to the set: $$\{(0,2),(1,1),(2,1)\}.$$ This is neither a vertical nor horizontal line, so we have $N(f^\lhd)>6$. Thus $f$ and $f^\lhd$ are nonequivalent Sudoku solutions. (In fact it is easy to see that the $18$ elements of $C$ which do not map to horizontal or vertical lines all map to distinct images in ${\mathbb{F}_3}^2$, so $N(f^\lhd)=24$).

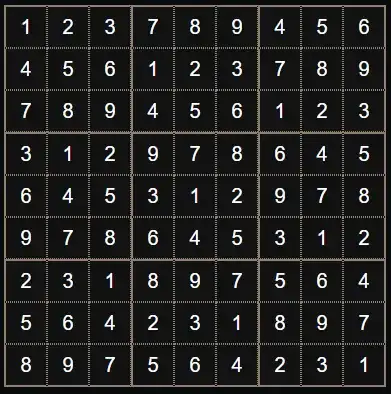

In conventional Sudoku terms, $f$ is essentially the first solution in Jade Vanadium's answer, and we obtain $f^\lhd$ from $f$ by swapping the 2nd and 7th columns. This transformation does not in general preserve solutions, but it does in this case because $f$ has so much symmetry. The set $C$ is just the set of thirds, so the invariant $N$ is very similar to the one in Jade Vanadium's answer. In fact it is clear that if you swap the 1st and 4th columns in Jade Vanadium's first solution, then the pair $1,2$ will occur in the same third in precisely $5\notin\{0,9\}$ of the boxes.