The second equation presented by you, $\boldsymbol{\nabla} \bigl( \boldsymbol{a} \cdot \boldsymbol{b} \bigr) = \: \bigl( \boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{a} \bigr) \! \cdot \boldsymbol{b} \, + \: \bigl( \boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{b} \bigr) \! \cdot \boldsymbol{a}$, is the primary one and it is pretty easy to derive (*

*) here I use the same notation as I did in my previous answers divergence of dyadic product using index notation and Gradient of cross product of two vectors (where first is constant)

$$\boldsymbol{\nabla} \bigl( \boldsymbol{a} \cdot \boldsymbol{b} \bigr) \!

\, = \, \boldsymbol{r}^i \partial_i \bigl( \boldsymbol{a} \cdot \boldsymbol{b} \bigr) \!

\, = \, \boldsymbol{r}^i \bigl( \partial_i \boldsymbol{a} \bigr) \! \cdot \boldsymbol{b} \, + \, \boldsymbol{r}^i \boldsymbol{a} \cdot \bigl( \partial_i \boldsymbol{b} \bigr)

\, = \: \bigl( \boldsymbol{r}^i \partial_i \boldsymbol{a} \bigr) \! \cdot \boldsymbol{b} \, + \, \boldsymbol{r}^i \bigl( \partial_i \boldsymbol{b} \bigr) \! \cdot \boldsymbol{a} \, =$$

$$= \: \bigl( \boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{a} \bigr) \! \cdot \boldsymbol{b} \, + \, \bigl( \boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{b} \bigr) \! \cdot \boldsymbol{a}$$

Again, I use the expansion of nabla as linear combination of cobasis vectors with coordinate derivatives ${\boldsymbol{\nabla} \! = \boldsymbol{r}^i \partial_i}$ (as always ${\partial_i \equiv \frac{\partial}{\partial q^i}}$), the product rule for $\partial_i$ and the commutativity of dot product of any two vectors (for sure, coordinate derivative of some vector $\boldsymbol{w}$, $\partial_i \boldsymbol{w} \equiv \frac{\partial}{\partial q^i} \boldsymbol{w} \equiv \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{w}}{\partial q^i}$, is a vector and not some more complex tensor) – here ${\boldsymbol{a} \cdot \bigl( \partial_i \boldsymbol{b} \bigr) = \bigl( \partial_i \boldsymbol{b} \bigr) \cdot \boldsymbol{a}}$. Again, I swap multipliers to get full nabla $\boldsymbol{\nabla}$ at the second term

For your first equation, the one with cross products, I need to mention the completely asymmetric isotropic Levi-Civita (pseudo)tensor of third complexity, ${^3\!\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}$

$${^3\!\boldsymbol{\epsilon}} = \boldsymbol{r}_i \times \boldsymbol{r}_j \cdot \boldsymbol{r}_k \; \boldsymbol{r}^i \boldsymbol{r}^j \boldsymbol{r}^k = \boldsymbol{r}^i \times \boldsymbol{r}^j \cdot \boldsymbol{r}^k \; \boldsymbol{r}_i \boldsymbol{r}_j \boldsymbol{r}_k$$

or in orthonormal basis with mutually perpendicular unit vectors $\boldsymbol{e}_i$

$${^3\!\boldsymbol{\epsilon}} = \boldsymbol{e}_i \times \boldsymbol{e}_j \cdot \boldsymbol{e}_k \; \boldsymbol{e}_i \boldsymbol{e}_j \boldsymbol{e}_k = \;\epsilon_{ijk}\! \boldsymbol{e}_i \boldsymbol{e}_j \boldsymbol{e}_k$$

(some more details about this (pseudo)tensor can be found at Question about cross product and tensor notation)

Any cross product, including “curl” (a cross product with nabla), can be represented via dot products with the Levi-Civita (pseudo)tensor (**

**) it is pseudotensor because of $\pm$, being usually assumed “$+$” for “left-hand” triplet of basis vectors (where ${\boldsymbol{e}_1 \times \boldsymbol{e}_2 \cdot \boldsymbol{e}_3 \equiv \;\epsilon_{123} \: = -1}$) and “$-$” for “right-hand” triplet (where ${\epsilon_{123} \: = +1}$)

$$\pm \, \boldsymbol{\nabla} \times \boldsymbol{b} = \boldsymbol{\nabla} \cdot \, {^3\!\boldsymbol{\epsilon}} \cdot \boldsymbol{b} = {^3\!\boldsymbol{\epsilon}} \cdot \! \cdot \, \boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{b}$$

For the pair of cross products that “pseudo” is compensated. As the very relevant example

$$\boldsymbol{a} \times \bigl( \boldsymbol{\nabla} \! \times \boldsymbol{b} \bigr) = \boldsymbol{a} \cdot \, {^3\!\boldsymbol{\epsilon}} \cdot \, \bigl( \boldsymbol{\nabla} \cdot \, {^3\!\boldsymbol{\epsilon}} \cdot \boldsymbol{b} \bigr) = \boldsymbol{a} \cdot \, {^3\!\boldsymbol{\epsilon}} \cdot \, \bigl( {^3\!\boldsymbol{\epsilon}} \cdot \! \cdot \, \boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{b} \bigr) = \boldsymbol{a} \cdot \, {^3\!\boldsymbol{\epsilon}} \cdot {^3\!\boldsymbol{\epsilon}} \cdot \! \cdot \, \boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{b}$$

Now I’m going to dive into components, and I do it by measuring tensors using some orthonormal basis (${\boldsymbol{a} = a_a \boldsymbol{e}_a}$, ${\boldsymbol{b} = b_b \boldsymbol{e}_b}$, ${\boldsymbol{\nabla} \! = \boldsymbol{e}_n \partial_n}$, ...)

$$\boldsymbol{a} \cdot \, {^3\!\boldsymbol{\epsilon}} \cdot {^3\!\boldsymbol{\epsilon}} \cdot \! \cdot \, \boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{b}

= a_a \boldsymbol{e}_a \; \cdot \epsilon_{ijk}\! \boldsymbol{e}_i \boldsymbol{e}_j \boldsymbol{e}_k \; \cdot \epsilon_{pqr}\! \boldsymbol{e}_p \boldsymbol{e}_q \boldsymbol{e}_r \cdot \! \cdot \, \boldsymbol{e}_n \left( \partial_n b_b \right) \boldsymbol{e}_b

= a_a \! \epsilon_{ajk}\! \boldsymbol{e}_j \!\epsilon_{kbn}\! \left( \partial_n b_b \right)$$

There’s a relation (too boring to derive it one more time) for contraction of two Levi-Civita tensors, saying

$$\epsilon_{ajk} \epsilon_{kbn} \: = \: \bigl( \delta_{ab} \delta_{jn} \! - \delta_{an} \delta_{jb} \bigr)$$

Thence

$$a_a \! \epsilon_{ajk} \epsilon_{kbn}\! \left( \partial_n b_b \right) \boldsymbol{e}_j

= \, a_a \bigl( \delta_{ab} \delta_{jn} \! - \delta_{an} \delta_{jb} \bigr) \! \left( \partial_n b_b \right) \boldsymbol{e}_j

= \, a_a \delta_{ab} \delta_{jn} \! \left( \partial_n b_b \right) \boldsymbol{e}_j

- a_a \delta_{an} \delta_{jb} \! \left( \partial_n b_b \right) \boldsymbol{e}_j =$$

$$= \, a_b \! \left( \partial_n b_b \right) \boldsymbol{e}_n

- \, a_n \! \left( \partial_n b_b \right) \boldsymbol{e}_b

= \left( \boldsymbol{e}_n \partial_n b_b \right) a_b

- \, a_n \! \left( \partial_n b_b \boldsymbol{e}_b \right)

= \left( \boldsymbol{e}_n \partial_n b_b \boldsymbol{e}_b \right) \cdot a_a \boldsymbol{e}_a

- \, a_a \boldsymbol{e}_a \! \cdot \left( \boldsymbol{e}_n \partial_n b_b \boldsymbol{e}_b \right)$$

Back to the direct invariant tensor notation

$$\left( \boldsymbol{e}_n \partial_n b_b \boldsymbol{e}_b \right) \cdot a_a \boldsymbol{e}_a = \: \bigl( \boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{b} \bigr) \! \cdot \boldsymbol{a}$$

$$a_a \boldsymbol{e}_a \! \cdot \left( \boldsymbol{e}_n \partial_n b_b \boldsymbol{e}_b \right) = \boldsymbol{a} \cdot \bigl( \boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{b} \bigr)$$

Sure, the latter one can also be written as

$$\boldsymbol{a} \cdot \bigl( \boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{b} \bigr) \!

\, = \, a_a \boldsymbol{e}_a \! \cdot \left( \boldsymbol{e}_n \partial_n b_b \boldsymbol{e}_b \right)

\, = \, \left( a_a \boldsymbol{e}_a\! \cdot \boldsymbol{e}_n \partial_n \right) b_b \boldsymbol{e}_b

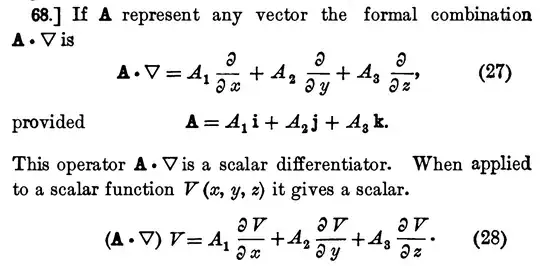

\, = \: \bigl( \boldsymbol{a} \cdot \boldsymbol{\nabla} \bigr) \boldsymbol{b}$$

And finally (***

***) it looks like meanwhile I also answered to Formula of the gradient of vector dot product

$$\boldsymbol{a} \times \bigl( \boldsymbol{\nabla} \! \times \boldsymbol{b} \bigr)

= \: \bigl( \boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{b} \bigr) \! \cdot \boldsymbol{a} \: - \: \boldsymbol{a} \cdot \bigl( \boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{b} \bigr)$$

or

$$\boldsymbol{a} \times \bigl( \boldsymbol{\nabla} \! \times \boldsymbol{b} \bigr)

= \: \bigl( \boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{b} \bigr) \! \cdot \boldsymbol{a} \: - \: \bigl( \boldsymbol{a} \cdot \boldsymbol{\nabla} \bigr) \boldsymbol{b}$$

or

$$\bigl( \boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{b} \bigr) \! \cdot \boldsymbol{a} = \: \bigl( \boldsymbol{a} \cdot \boldsymbol{\nabla} \bigr) \boldsymbol{b} \: + \: \boldsymbol{a} \times \bigl( \boldsymbol{\nabla} \! \times \boldsymbol{b} \bigr)$$

I hope now it’s easy enough for everyone to get similar relations for $\bigl( \boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{a} \bigr) \! \cdot \boldsymbol{b}$ and “yes” for question Are these equivalent?