Short Version:

I am interested in computing (as a closed form) the limit if it does exist:

$$ \lim_{k \rightarrow \infty} \left[\sum_{a^2+b^2 \le k^2; (a,b) \ne 0} \frac{1}{a^2+b^2} - 2\pi\ln(k) \right] $$

And if it does not exist but that difference happens to limit to a periodic function then I am interested instead in computing its average value that is:

$$ \lim_{k \rightarrow \infty} \text{Average}_{m \in [1,k]} \left[\sum_{a^2+b^2 \le m^2; (a,b) \ne 0} \frac{1}{a^2+b^2} - 2\pi\ln(m) \right] $$

If both of these assumptions are wrong then a proof of why they are wrong would also be an accepted answer.

Setup:

The following sum is known to diverge.

$$\sum_{(a,b) \in \mathbb{Z}^2; (a,b) \ne (0,0)} \frac{1}{a^2+b^2} $$

It can be viewed as a 2-dimensional variation of the divergent harmonic sum $$\sum_{n \in \mathbb{Z}; n \ne 0}^{\infty} \frac{1}{n} $$

The harmonic series has a nice expansion of the form

$$ \sum_{|n| \le k; n \ne 0, }^{} \frac{1}{n} = 2\ln(k) + 2\gamma + O \left( \frac{1}{n} \right) $$

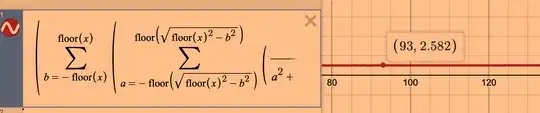

I was looking to compute the same for the quadratic sum. After experimentally tinkering with Desmos here:

It really does appear that

$$ \sum_{a^2+b^2 \le k^2; (a,b) \ne 0} \frac{1}{a^2+b^2} = 2\pi \ln(k) + \text{some periodic function} + O\left(\frac{1}{n}\right) $$

But I have no proof of this at this time. Now that periodic function seems to have an average value of around 2.5 (if you play with the desmos link)

Question:

Can that 2.5ish constant be expressed as a closed form with any known constants? There are a ton of constants we have now in the 21st century that Euler didn't have when he invented his $\gamma$. I would be hopeful that a closed form for something this "simple-looking" (its just replacing the harmonic series with a quadratic one instead) should exist.

A start might be to be very optimistic and just assume that

$$ \lim_{k \rightarrow \infty} \left[\sum_{a^2+b^2 \le k^2; (a,b) \ne 0}\frac{1}{a^2+b^2} - 2\pi\ln(k) \right] $$

Exists and is a constant (i.e. the periodic looking function limits to a constant) much like Euler did back in his day. If this could be a transformed into a nice integral some cleo-like magic might be able to resolve it in terms of known things.

Some Ideas:

The usual generalization of Euler Mascheroni constant are the Stieltjes Constants but they involve adding logarithmic weights to the harmonic series as opposed to replacing the harmonic series with a divergence quadratic series.

Also a closely related fact is that individual slices of this divergent sum do converge. For example famously $\sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{1}{n^2} = \frac{\pi^2}{6}$. This is a 1-D slice of our divergent 2-D sum (with angle 0). I believe for any rational angle the corresponding sum converges and I would really not be surprised if they all had closed forms nicely related to the Riemann zeta function.