tl; dr: No such simple rectifiable closed curve of length $\ell < 2e$ exists.

I lean toward believing no such curve exists regardless of (finite) length, but don't see a promising approach.

Fix a positive real number $\ell$. Let $\gamma$ be a simple rectifiable closed path of length $\ell$, parametrized by arc length on $[0, \ell]$. We'll view the choice of starting/ending point $\gamma(0)$ as the choice of point from which we draw chords. (For definiteness, assume the target space of $\gamma$ is an arbitrary-dimensional Euclidean space with distance function $d$; this can be generalized.)

Introduce the chordal distance function

$$

d(s) = d\bigl(\gamma(0), \gamma(\ell s)\bigr),\quad 0 \leq s \leq 1.

$$

This function is continuous, non-negative, $1$-periodic (if we extend $\gamma$ by periodicity), and zero precisely at integers.

The periodic extension of $d$ satisfies

$$

d(s) \leq \ell|s|\quad\text{for $|s| \leq \tfrac{1}{2}$},

$$

since the chordal distance from $\gamma(0)$ to $\gamma(\ell s)$ does not exceed the "short" arc length $\ell|s|$ from $0$ to $\ell s$ along $\gamma$. This inequality is key to non-existence below.

(Generally, in fact, the triangle inequality guarantees $d$ is Lipschitz with constant $\ell$: For all real $s$ and $t$,

$$

d(t) \leq d(s) + d\bigl(\gamma(\ell s), \gamma(\ell t)\bigr)

\leq d(s) + \ell|s - t|,

$$

and similarly with the roles of $s$ and $t$ reversed. That is,

$$

|d(s) - d(t)| \leq \ell|s - t|.

$$

Lipschitz continuity is used below only to make a geometric observation.)

For each integer $n \geq 2$, the points $\gamma(\frac{\ell j}{n})$ with $1 \leq j < n$ are "equally-spaced" along $\gamma$. The product of chord lengths is

$$

C(n) := \prod_{j=1}^{n} d(\tfrac{j}{n}).

$$

From now on, assume there exists a positive real number $C$ such that $C(n) = C$ for all $n \geq 2$. Our goal is to show no chordal distance function $d$ exists. This implies no such path $\gamma$ exists.

It will be convenient to (harmlessly) shift the domain of $d$ to be $[-\frac{1}{2}, \frac{1}{2}]$. If we divide $\gamma$ into $2n$ equal-length arcs, and "pair up" symmetrically-placed chord lengths, the resulting product is

$$

C = d(\tfrac{1}{2}) \cdot \prod_{j = 1}^{n-1} d(-\tfrac{j}{2n}) \cdot d(\tfrac{j}{2n}),

$$

independently of $n$. Our bound $|d(s)| \leq \ell|s|$ implies

\begin{align*}

C &\leq \tfrac{1}{2} \ell \cdot \prod_{j = 1}^{n-1} \biggl(\frac{\ell j}{2n}\biggr)^{2} \\

&= \frac{\ell^{2n-1}[(n-1)!]^{2}}{2^{2n-1} n^{2n-2}}

= \frac{\ell^{2n-1}[n!]^{2}}{2^{2n-1} n^{2n}}.

\end{align*}

By the weak version of Stirling's formula, $n! < n^{n}\sqrt{n}/e^{n-1}$, we have

$$

C < ne \biggl(\frac{\ell}{2e}\biggr)^{2n-1}\quad\text{for all $n \geq 2$.}

$$

If $\ell < 2e$, the expression in parentheses is smaller than $1$, so the upper bound converges to $0$ as $n \to \infty$. Particularly, no path of length $\ell < 2e$ has constant products of chord lengths. This completes the proof of the assertion above.

<>

Since I'm unlikely to have time to work more on this in the near future, here are some additional observations that arose while thinking about this:

On one hand the existence of a naive length bound is striking, particularly since the bound involves $e$. But as the proof shows, there's something distinctive about taking products of arbitrarily-many evenly-spaced values from a fixed positive function and requiring those products to stay bounded and bounded away from zero.

The value $C = d(\frac{1}{2})$ is the length of the arclength-bisecting chord from $\gamma(0)$. Consider the products of chord lengths obtained by dividing the arclength into quarters, eighths, sixteenths, and so on. Since

$$

C = \prod_{i=1}^{3} d(\tfrac{i}{4})

= d(\tfrac{1}{4}) \cdot d(\tfrac{1}{2}) \cdot d(\tfrac{3}{4})

$$

is positive, we have

$$

1 = \prod_{j=1}^{2} d(\tfrac{2j-1}{4})

= d(\tfrac{1}{4}) \cdot d(\tfrac{3}{4}).

$$

Similarly, since

$$

C = \prod_{i=1}^{7} d(\tfrac{i}{8})

= d(\tfrac{1}{8}) \cdot d(\tfrac{1}{4}) \cdot d(\tfrac{3}{8}) \cdot d(\tfrac{1}{2}) \cdot d(\tfrac{5}{8}) \cdot d(\tfrac{3}{4}) \cdot d(\tfrac{7}{8}),

$$

we have

$$

1 = d(\tfrac{1}{8}) \cdot d(\tfrac{3}{8}) \cdot d(\tfrac{5}{8}) \cdot d(\tfrac{7}{8}) = \prod_{j=1}^{4} d(\tfrac{2j-1}{8}).

$$

Generally,

$$

1 = \prod_{j=1}^{2^{n-1}} d(\tfrac{2j-1}{2^{n}})

$$

for every $n \geq 2$. In words, each time we bisect subintervals of $[-\frac{1}{2}, \frac{1}{2}]$ (or of $[0, 1]$), the product of the values of $d$ at the "newly-added" midpoints is unity.

The same is true, naturally, if we recursively subdivide $[0, 1]$ in an arbitrary way: The chord lengths of the initial subdivision multiply to $C$, and the product of chord lengths is preserved under subdivision, so the product of the "newly-added" chord lengths at each stage is unity.

In a related vein, if $\gamma$ has constant products of chord lengths, then for every $n \geq 2$ we have

\begin{align*}

C &= \prod_{j=1}^{n} d(-\tfrac{j}{2n+1}) \cdot d(\tfrac{j}{2n+1})

&& \text{$(2n + 1)$-gon;} \\

C^{2} &= \prod_{j=1}^{n} d(-\tfrac{j}{2n}) \cdot d(\tfrac{j}{2n})

&& \text{$2n$-gon, diameter double-counted;} \\[12pt]

1 &= \prod_{j=1}^{n-1} d(-\tfrac{j}{2n}) \cdot d(\tfrac{j}{2n})

&& \text{$2n$-gon, diameter omitted;} \\

C &= \prod_{j=1}^{n-1} d(-\tfrac{j}{2n-1}) \cdot d(\tfrac{j}{2n-1})

&& \text{$(2n -1)$-gon.}

\end{align*}

The first two products have $n$ factors; the last two have $(n - 1)$. Again, since $d$ is a fixed non-constant continuous function, these identities seem unlikely to be satisfiable. But I do not have a proof.

- Here is some prospectively-useful notation. We'll work in the set of rationals in $(0, 1)$. If $S$ is a finite set of rationals in $(0, 1)$, define $\Pi(S)$ to be the product of chord lengths $d(s)$ taken over $s$ in $S$:

$$

\Pi(S) = \prod_{s \in S} d(s).

$$

For example, let $n \geq 2$ be an integer, and let $Z_{n}^{*}$ denote the set of rationals $j/n$ such that $1 \leq j < n$. The "regular $n$-gon" with $\gamma(0)$ as a vertex has vertices $\gamma(\frac{\ell j}{n})$ with $1 \leq j < n$. By hypothesis, the product of chord lengths is

$$

C = \prod_{j=1}^{n-1} d(\tfrac{j}{n}) = \Pi(Z_{n}^{*}).

$$

For each integer $m \geq 2$, let $U(m) \subseteq Z_{m}^{*}$ denote the set of rational numbers $j/m$ such that $1 \leq j < m$ and $\gcd(j, m) = 1$; namely, such that $j/m$ is in lowest terms. The notation is motivated by abstract algebra: $j/m \in U(m)$ if and only if the residue class $[j]$ is invertible mod $m$.

If $p$ is prime, then $Z_{p}^{*} = U(p)$ (i.e., every non-zero residue class is invertible), so

$$

\Pi\bigl(U(p)\bigr) = \Pi\bigl(Z_{p}^{*}\bigr) = C.

$$

Generally, $Z_{n}^{*}$ is the disjoint union of $U(m)$ as $m$ runs through the non-trivial divisors of $n$. For example,

\begin{align*}

Z_{6}^{*}

&= \{\tfrac{1}{6}, \tfrac{1}{3}, \tfrac{1}{2}, \tfrac{2}{3}, \tfrac{5}{6}\} \\

&= \{\tfrac{1}{2}\} \cup \{\tfrac{1}{3}, \tfrac{2}{3}\} \cup \{\tfrac{1}{6}, \tfrac{5}{6}\} \\

&= U(2) \cup U(3) \cup U(6).

\end{align*}

Since $\Pi$ is multiplicative over disjoint unions, we have

$$

C = \Pi(Z_{6}^{*})

= \Pi\bigl(U(2)\bigr) \cdot \Pi\bigl(U(3)\bigr) \cdot \Pi\bigl(U(6)\bigr)

= C \cdot C \cdot \Pi\bigl(U(6)\bigr).

$$

We conclude that

$$

d(\tfrac{1}{6}) \cdot d(\tfrac{5}{6}) = \Pi\bigl(U(6)\bigr) = 1/C.

$$

In words, the product of the first and fifth chords in a "regular hexagon" is the reciprocal of the product of all five chord lengths. Arguing similarly, we can calculate $\Pi\bigl(U(m)\bigr)$ recursively for arbitrary $m \geq 2$.

In this notation, the calculations under item 1. may be written $\Pi\bigl(U(2^{k})\bigr) = 1$ if $k \geq 2$: We have $\Pi\bigl(U(2)\bigr) = C$, and

$$

Z_{2^{k}}^{*} = U(2) \cup U(4) \cup U(8) \cup \cdots \cup U(2^{k}).

$$

These lines of thought arose in trying to force a discontinuity in $d$, either at $0$ or at $\frac{1}{2}$. The difficulty appears to be that although $d$ must be uniformly continuous, the number of factors $n$ in a product is inversely proportional to the "sample spacing" $1/n$. When the number of factors is large, small changes in individual factors can have a large effect on the product.

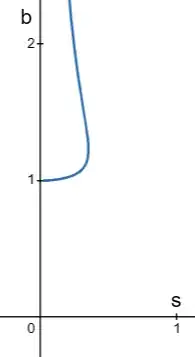

- Inversely, if there exists a continuously-differentiable function $d$ that is positive except at integers and satisfies the "constant product of sample values" condition above, then the Lipschitz condition guarantees $|d'| \leq \ell$, and we can solve the differential equation

$$

d'(t)^{2} + d(t)^{2} \theta'(t)^{2} = \ell^{2}

$$

for $\theta$ on $[0, 1]$. The parametric curve

$$

\gamma(t) = \bigl(d(t) \cos\theta(t), d(t) \sin\theta(t)\bigr)

$$

satisfies the constant product of chord lengths condition relative to the origin. (I see no reason such a curve, if it exists, should be simple.)