Given a line segment with length $ a $, a line segment with length $ b $, a compass, and a straightedge (you can only measure line segments with lengths $a $ or $ b $), is it possible to construct a line segment with length $ ab $ or $ \frac{b}{a} $?

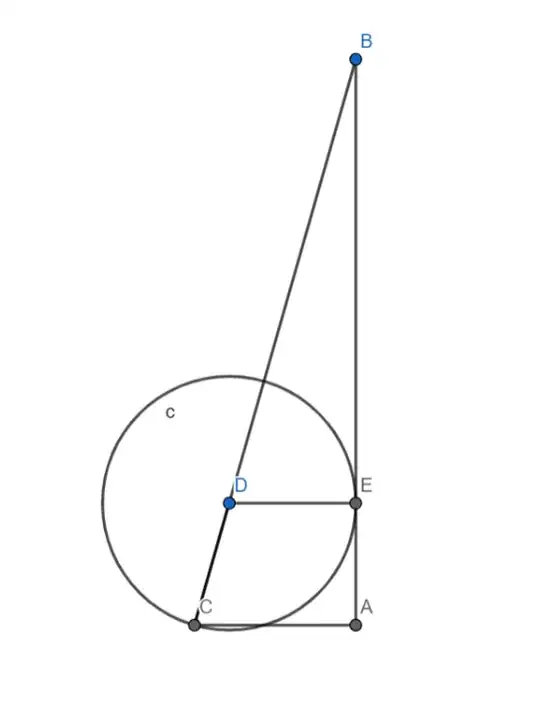

Motivation: In one of the geometric construction problems that I solved, I noticed that I constructed a line segment with length $ \frac{ab}{a+b} $. The construction is as follows: Assume $ b > a $. Draw a right-angle triangle $ABC$ with $ CA = a $ and $ BC = b $, where $ \angle A = 90^\circ $. Now draw the angle bisector of $ \angle C $. Let the point of intersection between the angle bisector of $ \angle C $ and $ \overline{AB} $ be $ E $, and draw a line parallel to $ \overline{AC} $ intersecting $ BC $ at $ F $. Let $ x := EF $; it is easy to see that $ DC = x $.

$$ \frac{x}{a} = \frac{b - x}{b} $$ $$ x = \frac{ab}{a + b} $$

I attempted to find a geometric construction for $ ab $ but was not successful.