I'm posting an answer to summarize the rather long comment thread before it likely gets moved to chat. In short, the problem in the question reduced to the fact that most classical proofs that the area of the unit circle is $\pi$ implicitly use $\theta \leq \tan \theta$ for $\theta \in (0,\pi/2)$. Then, the typical proof that $\theta \leq \tan \theta$ uses that the area of the unit circle is $\pi$, which is arguably circular.

For example:

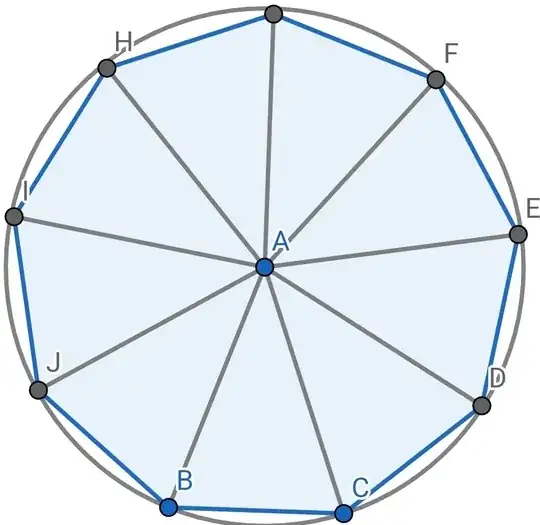

- Archimedes's proof essentially says "Since the perimeter of the polygon is greater than the circumference of the inscribed circle [...]"

- The usual proof of partitioning the circle into circular sectors and rearranging into a parallelogram/rectangle often just claims the length is $\pi$ by fiat (e.g. wikipedia's entry on the area of the circle does this) without mentioning it's actually $\pi \frac{\sin\delta_n}{\delta_n}$ for an appropriate $\delta_n$.

The problem with a modern, formal proof is "what do we even mean by the perimeter of the circle?" To answer this, we need some calculus.

In short, when it exists, we define the arc-length of the curve $\{(t,f(t)) : t \in [a,b]\}$ to be $$\int_a^b\sqrt{1 + (f'(t))^2}\,dt$$

(alternatively, we could define arc-length differently and then prove this as a theorem; all that matters is this formula gives something that extends polygonal "perimeter" in a natural way and it is sufficiently general for our purposes in this problem)

To consider the unit circle $x^2 + y^2 = 1$, we use $y = f(x) = \sqrt{1 - x^2}$. Then the circumference of the circle can be taken as the definition of $2\pi$, so that

$$\begin{align*}\pi &:= \int_{-1}^1\sqrt{1 + (f'(x))^2}\,dx \\ &= 2\int_0^1\frac1{\sqrt{1-x^2}}\,dx\end{align*}$$

The area of the circle, $A$, is given by

$$\begin{align*}

A &= 2\int_{-1}^1 f(x)\,dx \\

&= 4\int_0^1 \sqrt{1-x^2}\,dx \\

&= 2\int_0^1 \sqrt{1-x^2}\,dx + 2\int_0^1 (x)'\sqrt{1-x^2}\,dx \\

&= 2\int_0^1 \sqrt{1-x^2}\,dx - 2\int_0^1 x\left(\sqrt{1-x^2}\right)'\,dx \\

&= 2\int_0^1 \sqrt{1-x^2}\,dx + 2\int_0^1 \frac{x^2}{\sqrt{1-x^2}}\,dx \\

&= 2\int_0^1 \left(\sqrt{1-x^2} + \frac{x^2}{\sqrt{1-x^2}}\right)\,dx \\

&= 2\int_0^1 \frac1{\sqrt{1-x^2}}\,dx \\ &= \pi

\end{align*}$$

Note that this also proves that $\pi < \infty$ and therefore the corresponding arc-length integral exists (which possibly wasn't obvious from the original definition) as $A \leq 4$ since the circle sits inside the square $[-1,1]^2$