Choose three uniformly random points on a circle, and draw tangents to the circle at those points to form a triangle. (The triangle may or may not contain the circle.) For example:

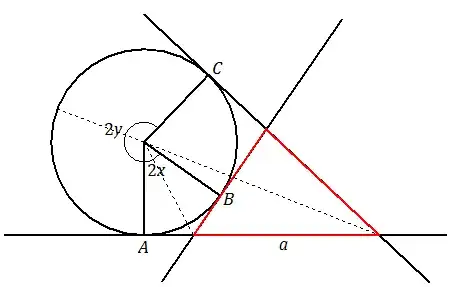

What is the probability, $P$, that a randomly chosen side of the triangle is shorter than the diameter of the circle?

I have found that $P=\frac12$ by using integration, and I will post my answer below. But since the probability is so simple, I am looking for an intuitive explanation.

(Having said that, a probability's simplicity is no guarantee that there is an intuitive explanation; for example here and here are probability questions that have answers of $1/2$ but have resisted intuitive explanations.)

Edit: If two or more of the tangent lines are parallel or coincident, re-choose the three points.