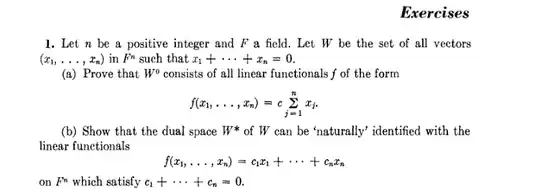

I worked out the details from leo's hint.

Consider the sequence of functions

$$W\rightarrow (F^n)^{*} \rightarrow W^{*}$$

where the first function is

$$(c_1,\dots,c_n)\mapsto f_{c_1,\dots,c_n}$$

where $f_{c_1,\dots,c_n}(x_1,\dots,x_n)=c_1x_1+\cdots c_nx_n$ and the second function is restriction from $F^n$ to $W$

We know both $W$ and $W^{*}$ have the same dimension. Thus if we show the composition of these two functions is one-to-one then it must be an isomorphism. Suppose $(c_1,\dots,c_n)\in W\mapsto f_{c_1,\dots,c_n}=0\in W^{*}$.

Then $\sum c_i=0$ and $\sum c_ix_i=0$ for all $(x_1,\dots,x_n)\in W$.

In other words $\sum c_i=0$ and $\sum c_ix_i=0$ for all $(x_1,\dots,x_n)$ such that $\sum x_i=0$.

Let $\{\alpha_1,\dots,\alpha_{n-1}\}$ be the basis for $W$ from part (a) ($\alpha_i$ has one in the first component and $-1$ in the $i$-th component). Then $f_{c_1,\dots,c_n}(\alpha_i)=0$ $\forall$ $ i=1,\dots,n-1$; which implies $c_1=c_i$ $\forall$ $i=2,\dots,n$. Thus $\sum c_i=nc_1$. But $\sum c_i=0$, thus $c_1=0$. Thus $f_{c_1,\dots,c_n}$ is the zero function.

Thus the mapping $W\rightarrow W^{*}$ is a natural isomorphism. We therefore naturally identify each element in $W^{*}$ with a linear functional $f(x_1,\dots,x_n)=c_1x_1+\cdots c_nx_n$ where $\sum c_i=0$.