The answer is, I believe, "no". Here's my reasoning.

$$

\newcommand{zz} {{\mathbb Z}}

$$

First, instead of considering the points of $S$ to be along some line through the origin (tilted at some angle $\theta$ clockwise from the $x$-axis), and projecting the lattice onto that line, let's consider our line to be the $x$-axis, and the lattice to be rotated counterclockwise by angle $\theta$. Thus a typical point of the lattice has coordinates

$$

k (\cos \theta, \sin \theta) + n (-\sin \theta, \cos \theta)

$$

I'll refer to this point as $[k, n]$ to save writing all those sines and cosines. Now the "projection" onto the line amounts to $[k, n] \mapsto k \cos \theta - n\sin \theta$, but that will be almost entirely irrelevant.

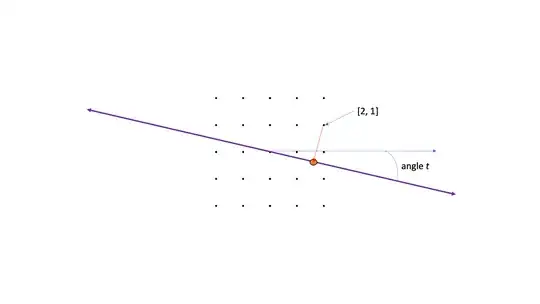

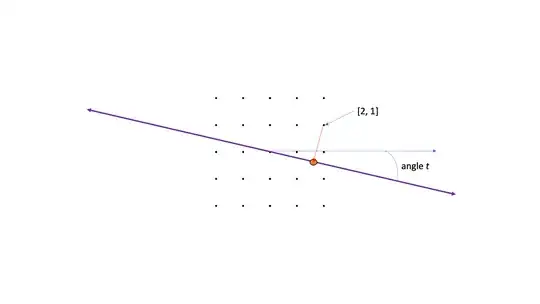

This picture shows the initial setup: integer lattice in black, sloped line in purple, a typical point $[2, 1]$ picked out, and its projection onto the line (red arrow, orange point).

After rotation by the angle $\theta$ (described as $t$ in the picture), the purple line becomes the $x$-axis, but the lattice point retains its name $[2, 1]$, even though the lattice is rotated by angle $\theta$.

Second, let's look at a kind of set mentioned in your comment, namely

$$

S = \{n \alpha \mid n \in \zz \} \cup \{n \beta \mid n \in \zz \}

$$

which I'll rewrite as

$$

S = \alpha \zz \cup \beta \zz,

$$

but for the special case $\alpha = \dfrac12$. I'll say what $\beta$ is shortly, but for now, it's just some number.

We're asking the question "Is there some sub-lattice of $\zz^2$ that projects to $S$?" Let's for the moment suppose that there is; then some point $[u, v]$ must project to $\alpha = 1/2$, and some point $[s, t]$ must project to $\beta$. (It's possible that multiple points will project to each, but I only need to name one.)

So let's look at each possible nonzero lattice point $[u, v]$ and ask "Is there some value of $\theta$ for which $[u, v]$ projects to $1/2$?" The point $[u, v]$ is at distance $r = \sqrt{u^2 + v^2}$ from the origin, so as $\theta$ ranges through all possible angles, $[u, v]$ sweeps out a circle of radius $r$ around the origin. Because $[u, v]$ is nonzero, $r$ is at least one. So this circle intersects the line $x = 1/2$ in two points. So there are two angles at which $[u, v]$ will project to the number $\alpha = 1/2$. (Explicitly, at $\theta_{uv} = \pm (\arccos(\frac{1/2}{r})-arccos(u/r))$, but we won't need that.)

To make this last remark explicit, let's look at the point shown in the first diagram above, $(2, 1)$. Its distance from the origin is $r = \sqrt{5} \approx 1.618$; its angle from the $x$-axis is $\arccos(2/\sqrt{5})\approx 26^{\circ}$. Rotating it by an angle of about $t = 50.5$ degrees sends it to

$$

(2 \cos t - 1 \sin t, 2 \sin t + 1 \cos t) \approx

(2 \times 0.636 - 0.772, 2 \times .772 + 0.636) \approx (0.5, 2.18).

$$

And in fact, rotating by angle $t$ or $-t$ are the only ways to make $[2, 1]$ project to the value $1/2$ on the $x$-axis.

Summary so far: if we want to find a rotated sublattice projecting to $S$, with $[u, v]$ projecting to $\frac{1}{2}$, then there are exactly two angles $\pm \theta_{uv}$ by which the lattice can be rotated to achieve this.

Since we're assuming there's a sublattice and projection solution, we know that if $[u, v]$ projects to $1/2$, then the angle must be $\pm \theta_{uv}$.

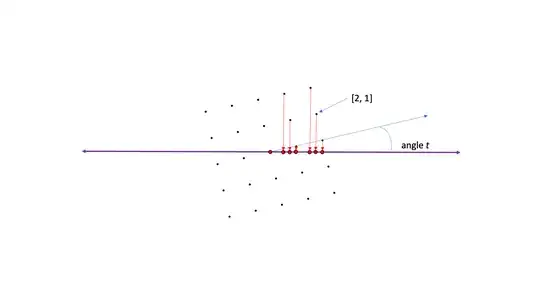

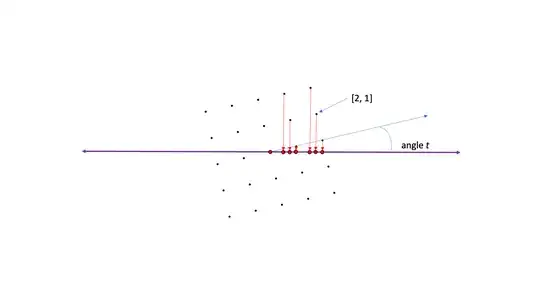

Now let's look at where other points of this rotated integer lattice might project. They'll project to some countably-infinite set of points, which I'm going to call $H_{uv}$. In particular, the projection of the special point $[s, t]$ --- the one that projects to $\beta$ --- must be in $H_{uv}$, or in other words, we must have $\beta \in H_{uv}$. This picture

shows how part of the rest of the (rotated) integer lattice from the earlier diagrams might project onto the line --- the red dots are the projections. If we squint a little and suppose that the point $[1, 2]$ (corresponding to the leftmost tall arrow) is actually projecting to the $x$-coordinate $0.5$ (it's not really!), then this set of red dots (and the others that I didn't draw) would be $H_{[1,2]}$.

Summary so far: if there's a sublattice projecting to $S$, and $[u, v]$ is a point of the sublattice that projects to $1/2$, then $\beta$ must be in $H_{uv}$.

Now let us ignore that "suppose" above, and ask "Could there be a rotated sublattice that projects to $S$?" The answer is "Yes, but only if there's some nonzero lattice point $[u, v]$ with the property that $H_{uv}$ contains $\beta$."

Now let's look at a rather large set of real numbers. Let

$$

L = \bigcup_{(u, v) \in \zz^2\\ (u, v) \ne (0,0)} H_{uv}.

$$

If $\beta$ is some number not in $L$, then $S$ cannot be the projection of any sublattice!

Now $L$ is a countable union of countable sets, and hence is a countable set. But the reals are uncountable, so $\mathbb R \setminus L$ is nonempty. If we pick $\beta$ to be any element of this set, then our set $S$ will not be the projection of any rotated lattice.