Clearly we have:

\begin{eqnarray}

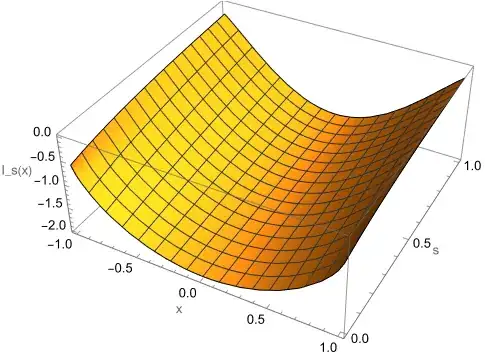

&&f_s(x):=\int\limits_{-1}^1 (1-y^2)^s \log|x-y| dy = \\

&&\int\limits_0^{1+x} (1-(x-y)^2)^s \log(y) dy +

\int\limits_0^{1-x} (1-(x+y)^2)^s \log(y) dy

%

\end{eqnarray}

Now

\begin{eqnarray}

f_s(0) &=& 2 \int\limits_0^1 (1-y^2)^2 \log(y) dy \\

&=& \frac{d}{d \theta} \frac{\Gamma(s+1) \Gamma(\theta/2+1/2)}{\Gamma(s/2+\theta/2+3/2)} |_{\theta=0} \\

&&\sqrt{\pi} \Gamma(1+s) \frac{\phi^{(0)}(1/2) - \phi^{(0)}(3/2+s)}{2 \Gamma(3/2+s)}

\end{eqnarray}

As for the derivatives we write the following:

\begin{eqnarray}

\left.\frac{d^n}{d x^n} f_s(x) \right|_{x=0} &=&

\int\limits_0^1

\frac{d^n}{d x^n}

\left(

\left.

\left(1-(x-y)^2\right)^s + \left(1-(x+y)^2\right)^s

\right)

\right|_{x=0} \log(y)

dy + \mbox{additional terms}\\

\end{eqnarray}

There are two things that need to be pointed out.

Firstly, for the calculation of the first term we will be using the Faa di Bruno formula with the external function being $x \rightarrow x^s$ and the internal function being equal to $x \rightarrow 1-(x+\epsilon y)^2$.

Secondly, we will be arguing that the additional terms disappear (even though some of them are singular) as $x \rightarrow 0$.

Thus we have:

\begin{eqnarray}

\left.\frac{d^n}{d x^n} f_s(x) \right|_{x=0} &=& \\

&=&

\sum\limits_{\epsilon=\pm}

\sum\limits_{m_2=0}^{\lfloor n/2 \rfloor} \frac{n!}{(n-2 m_2)! m_2!}

s_{(n-m_2)} (-1)^{m_2} (-2 \epsilon)^{n-2 m_2} \cdot

\underline{\int\limits_0^1 (1-y^2)^{s-(n-m_2)} y^{n-2 m_2} \log(y) dy} \\

&=&

\sum\limits_{\epsilon=\pm}

\sum\limits_{m_2=0}^{\lfloor n/2 \rfloor} \frac{n!}{(n-2 m_2)! m_2!}

s_{(n-m_2)} (-1)^{m_2} (-2 \epsilon)^{n-2 m_2} \cdot

\left. \underline{\frac{\Gamma \left(\frac{n+1}{2}\right) \Gamma (s+1) \left(H_{\frac{n-1}{2}}-H_{\frac{n+1}{2}+s}\right)}{4

\Gamma \left(\frac{n+3}{2}+s\right)}} \right|_{s \rightarrow s-(n-m_2), n \rightarrow n-2 m_2 }

\end{eqnarray}

The Mathematica code verifies the result:

{x} = RandomReal[{0, 1/10}, 1, WorkingPrecision -> 50]; M = 10;

s = RandomReal[{0, 1}, WorkingPrecision -> 50];

(*s=RandomInteger[{1,5}];*)

NIntegrate[(1 - (x - y)^2)^s Log[y], {y, 0, 1 + x}] +

NIntegrate[(1 - (y + x)^2)^s Log[y], {y, 0, 1 - x}];

Take[Accumulate@

Join[{(Sqrt[[Pi]]

Gamma[1 + s] (PolyGamma[0, 1/2] - PolyGamma[0, 3/2 + s]))/(

2 Gamma[3/2 + s])},

Table[Sum[

n!/((n - 2 m2)! m2!)

Pochhammer[s - (n - m2) + 1, n - m2] (-1)^

m2 ((-2) (eps))^(n - 2 m2) (

Gamma[(1 + n - 2 m2)/2] Gamma[

1 + s - (n - m2)] (HarmonicNumber[1/2 (-1 + n - 2 m2)] -

HarmonicNumber[(1 + n - 2 m2)/2 + s - (n - m2)]))/(

4 Gamma[(3 + n - 2 m2)/2 + s - (n - m2)]), {m2, 0,

Floor[n/2]}, {eps, -1, 1, 2}] x^n/n!, {n, 1,

M}]], -5] // MatrixForm

NIntegrate[(1 - y^2)^s Log[Abs[x - y]], {y, -1, 1},

WorkingPrecision -> 30]

Now, to answer your question.

First of all note that the following identity holds true:

\begin{eqnarray}

&&\sum\limits_{\epsilon=\pm}

\sum\limits_{m_2=0}^{\lfloor n/2 \rfloor}

\frac{n!}{(n-2 m_2)! m_2 !} s_{(n-m_2)} (-1)^{m_2} (-2 \epsilon)^{n-2 m_2}

\Gamma(\frac{1+n-2 m_2}{2})

\Gamma(1+s-(n-m_2))

\frac{

H_{\frac{1}{2}(-1+n-2 m_2)}

-

H_{\frac{1+n-2 m_2}{2}+s-(n-m_2)}

}{4\Gamma(\frac{3+n-2 m_2}{2}+s-(n-m_2))} =\\

&&

(\frac{n}{2})! \frac{2^{n/2}}{(n-1)!!} (-1)^{n/2-1} 1_{n \% 2 == 0}

(n-1)! \sqrt{\pi}

\frac{\Gamma(s+1)}{\Gamma(s+3/2-n/2)} \frac{1}{\Gamma(1+n/2)}

\end{eqnarray}

for $n=1,2,3,\cdots$. See Update 1 below for the derivation.

In[393]:= s = RandomReal[{0, 1}, WorkingPrecision -> 200]; M = 14;

l1 = Table[

Sum[n!/((n - 2 m2)! m2!)

Pochhammer[s - (n - m2) + 1, n - m2] (-1)^

m2 ((-2) (eps))^(n - 2 m2) (

Gamma[(1 + n - 2 m2)/2] Gamma[

1 + s - (n - m2)] (HarmonicNumber[1/2 (-1 + n - 2 m2)] -

HarmonicNumber[(1 + n - 2 m2)/2 + s - (n - m2)]))/(

4 Gamma[(3 + n - 2 m2)/2 + s - (n - m2)]), {m2, 0,

Floor[n/2]}, {eps, -1, 1, 2}], {n, 1, M}];

l2 = Table[(n/2)! 2^(n/2)/(n - 1)!! If[Mod[n, 2] == 0, (-1)^(n/2 - 1),

0] (n - 1)! Sqrt[Pi] Gamma[

s + 1] 1/(Gamma[s + 3/2 - n/2] Gamma[1 + n/2]), {n, 1, M}];

l1 - l2

Out[396]= {0.10^-200, 0.10^-199 + 0.10^-200 I,

0.10^-198 + 0.10^-200 I, 0.10^-197 + 0.10^-198 I,

0.10^-196 + 0.10^-197 I, 0.10^-196 + 0.10^-197 I,

0.10^-195 + 0.10^-196 I, 0.10^-195 + 0.10^-196 I,

0.10^-193 + 0.10^-194 I, 0.10^-193 + 0.10^-194 I,

0.10^-191 + 0.10^-192 I, 0.10^-191 + 0.10^-192 I,

0.10^-189 + 0.10^-189 I, 0.10^-189 + 0.*10^-189 I}

What I wrote here before was a wrong conclusion that those quantities become identically zero for $n$ big enough iff $s$ is a positive integer. This wrong conclusion was based on analysing the Pochhammer factor $s_{(n-m_2)}$ in the left hand side of the above identity. But what is more important is the Gamma function in the denominator of the left hand side! Indeed if we take $n$ even and $s$ positive half integer then for $n$ being large enough the argument of the Gamma function in the denominator becomes a negative integer and as such the Gamma function is infinity and the both sides are identically zero.

So in short, the quantity $f_s(x)$ becomes a polynomial iff $s$ is a positive half integer.

Update:

From the above it is actually not quite clear as to whether the higher derivatives of $f_s(x)$ exist. We will therefore show in a different way that they all do exist. Here we go:

\begin{eqnarray}

f_s(x) &=& \int\limits_0^{1+x} (1-(x-y)^2)^s \log(y) dy +

\int\limits_0^{1-x} (1-(x+y)^2)^s \log(y) dy \\

&=&

\sum\limits_{n=0}^\infty \binom{s}{n} (-1)^n \sum\limits_{l=0}^{2 n} \binom{2n}{l} x^{2n-l}

\left[

(-1)^l \int\limits_0^{1+x} y^l \log(y) dy +

\int\limits_0^{1-x} y^l \log(y) dy

\right] \\

&=&

\sum\limits_{n=0}^\infty \binom{s}{n} (-1)^n \sum\limits_{l=0}^{2 n} \binom{2n}{l} x^{2n-l}

\left[

(-1)^l \left. \frac{y^{1+l} \left(-1+(1+l) \log(y)\right) }{(1+l)^2} \right|_0^{1+x} +

\left. \frac{y^{1+l} \left(-1+(1+l) \log(y)\right) }{(1+l)^2} \right|_0^{1-x}

\right] \\

&=&

\sum\limits_{n=0}^\infty \binom{s}{n} (-1)^n \sum\limits_{l=0}^{2 n} \binom{2n}{l} x^{2n-l}

\left[ \right. \\

&& \left.

(-1)^{l+1} \frac{(1+x)^{l+1}}{(1+l)^2} +

(-1) \frac{(1-x)^{l+1}}{(1+l)^2} + \right. \\

&&\left.

(-1)^{l} \frac{(1+x)^{l+1}}{(1+l)^1} \log(1+x) +

\frac{(1-x)^{l+1}}{(1+l)^1} \log(1-x)

\right. \\

&&\left.

\right]

\end{eqnarray}

We clearly see that the expression in square brackets above is $C^\infty(x)$ for every $l=0,1,2,\cdots$ and as such the whole expression is $C^\infty(x)$ as expected.

Update 1:

By using the expression for the $n$th derivative as given in the answer below given by Claudio and then by using the Pfaff transformation for the Gaussian hypergeometric function we found the following neat closed form expression for the function in question:

\begin{eqnarray}

f_s(x) &=& \sqrt{\pi} \Gamma(1+s) \frac{\phi^{(0)}(1/2) - \phi^{(0)}(3/2+s)}{2 \Gamma(3/2+s)} +\\

&&

\sum\limits_{n=1}^\infty \frac{2^n}{(2n-1)!!} (-1)^{n-1} (2n-1)! \sqrt{\pi} \frac{\Gamma(s+1)}{\Gamma(s+\frac{3}{2}-n)} \cdot \frac{x^{2n}}{(2n)!}

\end{eqnarray}

{x} = RandomReal[{0, 1}, 1, WorkingPrecision -> 50]; M = 40;

s = RandomReal[{0, 1}, WorkingPrecision -> 50];

ll = Join[{(

Sqrt[\[Pi]]

Gamma[1 + s] (PolyGamma[0, 1/2] - PolyGamma[0, 3/2 + s]))/(

2 Gamma[3/2 + s])}, Table[

2^(n)/(2 n - 1)!! (-1)^(n - 1) (2 n - 1)! Sqrt[Pi] Gamma[

s + 1] 1/(Gamma[s + 3/2 - n]) x^(2 n)/(2 n)!, {n, 1, M}]];

Take[Accumulate@ll, -5] // MatrixForm

NIntegrate[(1 - y^2)^s Log[Abs[x - y]], {y, -1, 1},

WorkingPrecision -> 30]

From the above it clearly follows that the expression is indeed a polynomial in $x$ if and only if $s$ is a positive half-integer.