I believe the core issue arises when using the power law. Consider the statement

$$

\log_{10} \Big[ (x+1)^2 \Big] = 2 \log_{10}(x+1) \tag{1}

$$

There is an implicit assumption here: that these are, in fact, equal. More precisely, that both sides of this equation represent defined quantities!

If you recall, any logarithmic function, $\log_a(x)$ ($a>0$), only defined for $x>0$, at least in traditional arithmetic.

Aside: You can deal with certain ideas that allow for values for other $x$'s, but these considerations generally don't arise until one takes an upper-level math class, so let's keep the discussion more grounded, and assume we want only real values of the function and hence $x>0$.

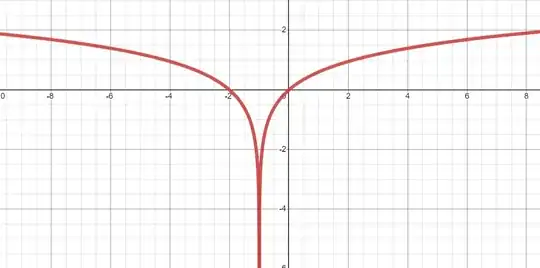

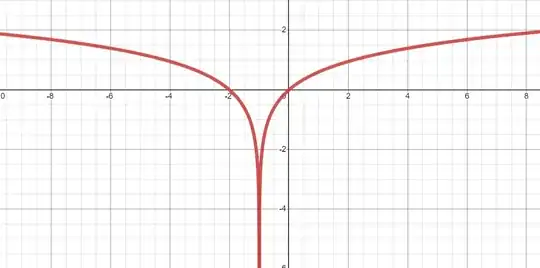

The left-hand side of $(1)$ is defined almost everywhere: $(x+1)^2 \ge 0$ just on merit of squaring a number, and in particular $(x+1)^2 > 0$ whenever $x \ne -1$. You can see this in the function's graph.

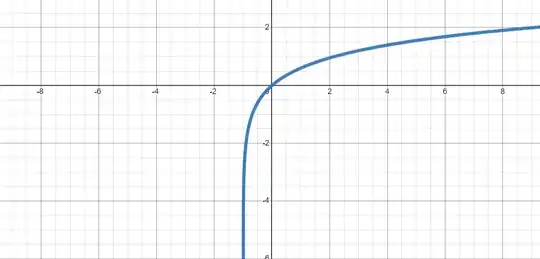

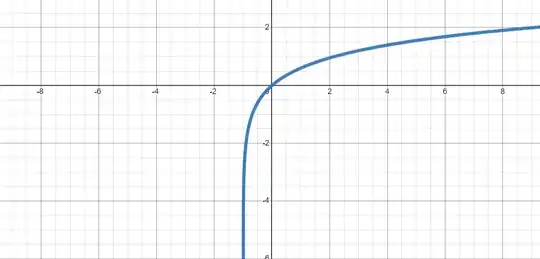

The same is not true of the right-hand side of $(1)$: it is only defined when $x+1 > 0$, i.e. when $x > -1$. So you have "lost" half of its graph:

More broadly, then, the power law can be stated as the following generalization:

$$

\log_a \Big[ f(x)^{b} \Big] = b \log_a \big[ f(x) \big] \text{ whenever } f(x) > 0

$$

Note: Technically, to ensure the left-hand side is valid, we should also state that $f(x)^b > 0$, but the function $g(x) = x^b$ is positive for any real value $b$, so this is a nonissue. Hence, $f(x)^b > 0$ if and only if $f(x) >0$.

The law you are familiar with is for the function $f(x)=x$, and hence likewise carries the stipulation:

$$

\log_a \left( x^{b} \right) = b \log_a ( x ) \text{ whenever } x > 0

$$

So when solving this equation $(1)$ by the power law method, what you have discovered is:

If this equation has a solution $x$, and $x>0$, then $x=9$

Of course, this doesn't exhaust the entire solution space: other solutions for $x \le 0$ may exist, as you have seen via other methods.