Do you mean that I need to introduce the variable with "let"? I just read a post about not using "let" for universal quantification.

The word "let" merely assigns meaning and does not in itself connote universal quantification. In any case, even though your opening clause "for any $(x,y)$" is ostensibly suggesting universal quantification, technically at this point in the proof you're merely dealing with an arbitrary $(x,y);$ this is indicated by the phrase "any $(x,y)$".

As such, you might as well just spell it out instead: "Let $(x,y)$ be arbitrary. Suppose that..." (the first sentence can be omitted and left tacit).

Alternatively, rewrite the opening sentence as

"Let $(x,y)$ be any element of $\left(A\times B\right)\cap \left(C\times D\right)$".

Would it be better to say: "Consider any $\left(x{,}y\right)\in \left(A\times B\right)\cap \left(C\times D\right)$" ?

Sure, this is good too.

Is the way that I introduce $(x,y)$ valid? Or does my wording mean $\forall x{,}y\left(\left(x{,}y\right)\in\left(A\times B\right)\cap\left(C\times D\right)\right)$ ?

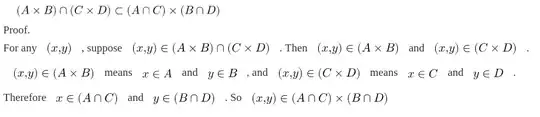

No, your opening sentence is not asserting that every $(x,y)$ belongs to that set intersection: it is merely introducing a couple then making a supposition—not an assertion—about it. The substance of your proof is fine.

When I conclude, do I need to say: "Since $(x,y)$ was arbitrary.." ?

Only if you wish to summarise your proof and explicitly display the theorem statement. This step can also be omitted and left tacit, depending on your preferred level of detail.

Addendum

Suppose that for any x, x∈Z means ∀x x∈Z, right ?

No: ∀x x∈Z means for each x, x∈Z (no "suppose that"), while suppose that for any x, x∈Z is not really an assertion/statement (the phrase "suppose that" roughly means "if").

On the other hand, suppose that for any x, x∈Z; then P is true is symbolised either as (∀x x∈Z) ⟹ P or (∃x x∈Z) ⟹ P, depending on the context: Translating 'any' as ∀ or ∃.