Here is my answer. My answer is something like 'algorism' solution. Actually I'm not satisfied with my answer. Please improve my answer.

I think we can find a center even in the case $l_1\parallel l_2$.

Note that im my answer I suppose that we've already known the information about $l_1, l_2$.

In the case of $l_1\parallel l_2$, letting $d_0$ be the distance between two lines $l_1, l_2$, note that $0<d_0<2$ because of $0<d_2\le d_1<2$. Without loss of generality, suppose that $l_1:y=0, l_2:y=d_0$. Let $r$ be the radius of a circle. According to $0<d_2\le d_1<2$, there are two cases:case1 is that there exists the center of a circle between two lines and case2 is that there is not the center of a circle between two lines. In the first case, since we get $d_0=\sqrt{r^2-\left(\frac{d_2}{2}\right)^2}+\sqrt{r^2-\left(\frac{d_1}{2}\right)^2}$, we can represent $r$ by $d_0, d_1, d_2$. Then, letting $l_3:y=r+\sqrt{r^2-\left(\frac{d_1}{2}\right)^2}$, there are two small cases: one is that $l_3$ and a circle come in contact with each other and the other is that $l_3$ neither crosses nor come in contact with any circle. In the first case, given a point $\left(a,r+\sqrt{r^2-\left(\frac{d_1}{2}\right)^2}\right)$, then we know the center of a circle is $\left(a,\sqrt{r^2-\left(\frac{d_1}{2}\right)^2}\right)$. If $l_3$ neither crosses nor come in contact with any circle, we know the situation is in case2. Letting $l_4:y=r-\sqrt{r^2-\left(\frac{d_1}{2}\right)^2}$, then you do get the point $\left(b,r-\sqrt{r^2-\left(\frac{d_1}{2}\right)^2}\right)$, so we know the center of a circle is $\left(b,-\sqrt{r^2-\left(\frac{d_1}{2}\right)^2}\right)$.

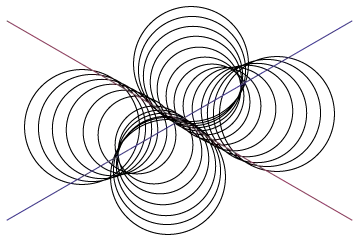

In the case of $l_1\not \parallel l_2$, I use Blue's idea(see comments below). We can move everything such that the intersection comes at the origin and that one of bisectors of two angles between two lines comes x-axis. Without loss of generality, suppose that $l_1:y=mx, l_2:y=-mx$. Letting $l_3:y=0$, we have three different cases: Case$1$ is that the origin is outside of a circle. Case$2$ is that the origin is on a circle. Case$3$ is that the origin is inside of a circle.

Case$1$: Suppose that the points $A, D$ are on the $l_1$ and $C, F$ on $l_2$ and $B, E$ on $l_3$ and that each of $A, B, C$ is nearer to the origin than the other. Letting $OA=a, OB=b, OC=c$, we get the following from the power of a point theorem. $$a(a+d_1 )=c(c+d_2 ), a(a+d_1 )=b(b+d_3 )$$

Then, we can represent $b,c$ by $a, d_i$. After a tedious calculation, we know we can represent every coordinates by $a, d_i$. Then, letting $4(a^2+ad_1 )=k$, we know the following has to be satisfied:$$\left(\sqrt{(d_1)^2+k}+\sqrt{(d_2)^2+k}\right){\sqrt{1+m^2}}=2\sqrt{(d_3)^2+k}$$

By $a=\frac{-d_1+\sqrt{(d_1)^2+k}}{2}$, we know we can represent every coordinates and the center of a circle by $k,d_i, m$. Hence, this is a conclusion: If there exists a positive real number $k$ such that $$\left(\sqrt{(d_1)^2+k}+\sqrt{(d_2)^2+k}\right){\sqrt{1+m^2}}=2\sqrt{(d_3)^2+k},$$(you can get this from $j$ below represented in two ways)and the radius is less than or equals $1$, then the center of a circle can be found: $$(i,j)=\left(b+\frac{d_3}{2},\frac{2b+d_3-(2c+d_2)\sqrt{1+m^2}}{2m}\right)$$ with $$b=\frac{-d_3+\sqrt{{d_3}^2+k}}{2}, c=\frac{-d_2+\sqrt{{d_2}^2+k}}{2}.$$ And the radius is $$r=\sqrt{(b-i)^2+j^2}.$$However, the radius and the coordinates of a center are so complicated that I can't calculate them any more. In the Case$2$ and Case$3$, alomost same argument can be done. Case$2$ is easier than the others. In the case$3$, I have another difficulty: ambiguity in the signs. Strictly speaking, I think we can't decide just one answer. In other words, there remains several possibilities and it's hard to consider the conditions about possibilities.

My answer is like an 'algorism' solution. This is why I'm not satisfied with this answer.

Could you give me any hint or another better idea?

Edit: I hope the following two are useful.

I'll use the same alphabets as Blue used.

$1$. Since each of $l_1, l_2$ crosses a circle, considering each of the discriminants of the followings:

$$(x-h)^2+(\pm x\tanθ-k)^2=r^2,$$

we get $$\left(-h\mp k\tanθ\right)^2-\left(1+\tan^2θ\right)\left(h^2+k^2-r^2\right)>0$$

$$⇔\ \left(k\mp h\tanθ\right)^2<r^2\left(1+\tan^2θ\right)⇔\ r^2>\frac{(k\mp h\tanθ)^2}{1+\tan^2θ}⇔\ r>\frac{|k\mp h\tanθ|}{\sqrt{1+\tan^2θ}}.$$

Since $r$ is less than or equals to $1$, we get$$\frac{|k\mp h\tanθ|}{\sqrt{1+\tan^2θ}}<1⇔\ |k\mp h\tanθ|<\sqrt{1+\tan^2θ}$$

$$⇔\ h\tanθ-\sqrt{1+\tan^2θ}<k<h\tanθ+\sqrt{1+\tan^2θ},$$$$ -h\tanθ-\sqrt{1+\tan^2θ}<k<-h\tanθ+\sqrt{1+\tan^2θ}.$$

This shows the region in which the center of a circle can be exist.

$2$. Considering the situation that a circle $(x-h)^2+(y-k)^2=r^2$ passes two points $(0,0), (d,0)$, we get $$h=\frac d2, r=\sqrt{\frac{d^2}{4}+k^2}.$$ Since $r$ is less than or equals to $1$, we get $$-\sqrt{1-\frac{d^2}{4}}\le k\le \sqrt{1-\frac{d^2}{4}}$$ for a real number $d$ which satisfies $0\le d\le 2$.

Since we've already known that the lengths of the chords of a circle by two lines $l_1, l_2$ are $d_1, d_2$$(2>d_1\ge d_2>0)$respectively, by the argument above, we know that the center of a circle does exist in a parallelogram-shaped region whose center is the origin: the length of its edges are $2\sqrt{1-\frac{{d_1}^2}{4}}, 2\sqrt{1-\frac{{d_2}^2}{4}}$.

I've tried to find a new line $l_3$ instead of $x=0$, but I'm facing difficulty.

Edit $2$: I've got the following which would be useful.

Let each of $l_{1,d+}, l_{1,d-}, l_{2,D+}, l_{2,D-}$ be the followings:$$l_{1,d+}:y=x\tanθ+\frac{d}{\cosθ}, l_{1,d-}:y=x\tanθ-\frac{d}{\cosθ}$$

$$l_{2,d+}:y=-x\tanθ+\frac{D}{\cosθ}, l_{2,d-}:y=-x\tanθ-\frac{D}{\cosθ},$$

where $D=\sqrt{d^2+\frac{{d_1}^2-{d_2}^2}{4}}.$

Note that each distance between $l_1$ and $l_{1,d\pm}$ is $d$, and that each distance between $l_2$ and $l_{2,d\pm}$ is $D$. Also, note the following:

$$\sqrt{\left(\frac{d_1}{2}\right)^2+d^2}=\sqrt{\left(\frac{d_2}{2}\right)^2+D^2}.$$

This means that the radius of a circle which crosses $l_1$ equals to the radius of a circle which crosses $l_2$. Note that $d$ must satisfy the following because of what I've already written above:$$0\le d\le \sqrt{1-\frac{{d_1}^2}{4}}.$$

Then, Letting each of the intersections of $l_{1,d-}, l_{2,D+}$ and $l_{1,d+}, l_{2,D+}$ and $l_{1,d+}, l_{2,D-}$ and $l_{1,d-}, l_{2,D-}$ be $P_{-+}$, $P_{++}$, $P_{+-}$, $P_{--}$ respectively, we can represent these as the follwoings:

$$P_{-+}\ \left(\frac{d+D}{2\sinθ}, \frac{D-d}{2\cosθ}\right), P_{++}\ \left(\frac{-d+D}{2\sinθ}\frac{d+D}{2\cosθ}\right),$$$$P_{+-}\ \left(\frac{-d-D}{2\sinθ}, \frac{d-D}{2\cosθ}\right), P_{--}\ \left(\frac{d-D}{2\sinθ}, \frac{-d-D}{2\cosθ}\right).$$

Since each radius is $\sqrt{d^2+\frac{{d_1}^2}{4}}$, we can represent the circles as followings:

$$C_{-+}:\left(x-\frac{d+D}{2\sinθ}\right)^2+\left(y-\frac{D-d}{2\cosθ}\right)^2=d^2+\frac{{d_1}^2}{4}$$

$$C_{++}:\left(x-\frac{-d+D}{2\sinθ}\right)^2+\left(y-\frac{d+D}{2\cosθ}\right)^2=d^2+\frac{{d_1}^2}{4}$$

$$C_{+-}:\left(x-\frac{-d-D}{2\sinθ}\right)^2+\left(y-\frac{d-D}{2\cosθ}\right)^2=d^2+\frac{{d_1}^2}{4}$$

$$C_{--}:\left(x-\frac{d-D}{2\sinθ}\right)^2+\left(y-\frac{-d-D}{2\cosθ}\right)^2=d^2+\frac{{d_1}^2}{4}.$$

Let's consider the center of $C_{-+}$, which is $P_{-+}$. Letting $P_{-+}$ be $(x, y)$, then we get $d=x\sinθ-y\cosθ$. Putting it in the equation $2y\cosθ=D-d$, we get

$$xy=\frac{{d_1}^2-{d_2}^2}{16\sinθ\cosθ}.$$ Hence, we know that the point $P_{-+}$ is on a hyperbola for any $d$.

I've tried to find a special line which is tangent to $C_{-+}$ for any $d$, but I'm facing difficulty. I expect that we can solve this question in an elegant way. I hope I'm getting closer to it.

Edit$3$:

According to Blue's answer, using $l_3$ Blue wrote, we get

$$p=1-\frac{\sqrt{1-b^2}-\sqrt{1-a^2}}{2\sin\theta}>0$$

if $\theta\ge\ \pi/4$.

Also, using $l_4$ Blue wrote, we get

$$p=-1-\frac{\sqrt{1-a^2}-\sqrt{1-b^2}}{2\sin\theta}>0$$

if $0<\sin\theta<\frac{\sqrt{1-b^2}-\sqrt{1-a^2}}{2}(<\frac{1}{\sqrt2})$.

If $\phi=0,$ we get

$$0=16h^4\sin^3θ\cos^2θ+8h^2\sinθ\cos^2θ(a^2 +b^2 −2c^2 −2p^2)+8hp{\cosθ}(a^2−b^2 )-(a^2−b^2)^2\sinθ.$$

Hence, we know that there's exactly one positive root $h$ for any negative $p$.

Then,$$y=p=\frac{\sqrt{1-b^2}-\sqrt{1-a^2}}{2\cos\theta}-1<0$$

if $0<\theta\le \pi/4.$

$$y=p=\frac{\sqrt{1-a^2}-\sqrt{1-b^2}}{2\cos\theta}+1<0$$

if $0<\cos\theta<\frac{\sqrt{1-b^2}-\sqrt{1-a^2}}{2}(<\frac{1}{\sqrt2})$.

Hence, if $0<\theta<\alpha$ such that $\sin\alpha=\frac{\sqrt{1-b^2}-\sqrt{1-a^2}}{2}$, then we can choose the following lines:

$$l_3:x=\frac{\sqrt{1-a^2}-\sqrt{1-b^2}}{2\sin\theta}+1,$$

$$l_4:y=\frac{\sqrt{1-b^2}-\sqrt{1-a^2}}{2\cos\theta}-1.$$

If $\beta<\theta<\pi/2$ such that $\cos\beta=\frac{\sqrt{1-b^2}-\sqrt{1-a^2}}{2}$, then we can choose the following lines:

$$l_3:x=\frac{\sqrt{1-b^2}-\sqrt{1-a^2}}{2\sin\theta}-1,$$

$$l_4:y=\frac{\sqrt{1-a^2}-\sqrt{1-b^2}}{2\cos\theta}+1.$$

Then, the problem for $\alpha\le \theta\le \beta$ remains unsolved. I hope I'm not mistaken.

Edit$\ 4$:

As I've already written above, if $\phi=0$, we get

$$0=16h^4\sin^3\theta\cos^2\theta+8h^2\sin\theta\cos^2\theta\left(a^2+b^2-2c^2-2p^2\right)+8hp\cos\theta(a^2-b^2)-(a^2-b^2)^2\sin\theta\ \ \ \ \ \ \ \cdots(\star\star).$$

Changing $h$ to $-h$ in $(\star\star)$ gives us

$$0=16h^4\sin^3\theta\cos^2\theta+8h^2\sin\theta\cos^2\theta\left(a^2+b^2-2c^2-2p^2\right)-8hp\cos\theta(a^2-b^2)-(a^2-b^2)^2\sin\theta\ \ \ \ \ \ \ \cdots(\star\star\star).$$

Since we know that there's exactly one positive root $h$ for any positive $p$ in $(\star\star\star)$, we also know that there's exactly one negative root $h$ for any positive $p$ in $(\star\star)$.

In the following argument, suppose that

$$\cos\beta=\frac{\sqrt{1-b^2}-\sqrt{1-a^2}}{2}, \cos\gamma=\frac{\sqrt{1-a^2}+\sqrt{1-b^2}}{2}.$$

Note that if $a>b$, then

$$0<\frac{\sqrt{1-b^2}-\sqrt{1-a^2}}{2}<\frac{\sqrt{1-a^2}+\sqrt{1-b^2}}{2}<1.$$

By the argument above, I got the following:

When $0<\theta<\gamma$,

$$l_3:y=\frac{\sqrt{1-b^2}-\sqrt{1-a^2}}{2\cos\theta}-1\ (<0),$$

$$l_4:y=\frac{-\sqrt{1-a^2}-\sqrt{1-b^2}}{2\cos\theta}+1\ (>0).$$

When $\gamma<\theta<\beta$,

$$l_3:y=\frac{\sqrt{1-b^2}-\sqrt{1-a^2}}{2\cos\theta}-1\ (<0),$$

$$l_4:y=\frac{\sqrt{1-a^2}+\sqrt{1-b^2}}{2\cos\theta}-1\ (>0).$$

When $\beta<\theta<\pi/2$,

$$l_3:y=\frac{\sqrt{1-a^2}-\sqrt{1-b^2}}{2\cos\theta}+1\ (<0),$$

$$l_4:y=\frac{\sqrt{1-a^2}+\sqrt{1-b^2}}{2\cos\theta}-1\ (>0).$$

In each case, if $l_3$ crosses an invisible circle at two points, then $(\star\star)$ has exactly one positive root $h$. If $l_3$ neither crosses nor comes in contact with any circle, then $l_4$ gives us $c$, so we'll get exactly one negative root $h$ in $(\star\star)$.

Is this correct? Did I miss anything? I'm afraid I might be mistaken.

Edit $5$:

I got the following:

Letting $\sin\epsilon=\frac{\sqrt{1-a^2}}{2}, \cos\omega=\frac{\sqrt{1-a^2}}{2}$, note that $0<\epsilon<\omega<\pi/2$ for any $a$.

(i) When $0<\theta<\omega$, let's take $l_3$ to be the line:

$$y=\frac{\sqrt{1-b^2}-\sqrt{1-a^2}}{2\cos\theta}+1.$$

Note that this $l_3$ does cross any one of upper-right sub-family of circles because of the following:

$$\frac{\sqrt{1-a^2}+\sqrt{1-b^2}}{2\cos\theta}-1<\frac{\sqrt{1-b^2}-\sqrt{1-a^2}}{2\cos\theta}+1 ⇔ \cos\theta>\frac{\sqrt{1-a^2}}{2}.$$

If we get $c$, we can take a positive root (there's exactly one positive root) in $(\star\star)$ as $h$, because this $l_3$ never crosses the lower-left sub-family of circles: this is because for any $d_1>d_2$,

$$\frac{\sqrt{1-a^2}-\sqrt{1-b^2}}{2\cos\theta}+1<\frac{\sqrt{1-b^2}-\sqrt{1-a^2}}{2\cos\theta}+1.$$

Then, let's calculate $k=\frac{a^2-b^2}{4h\cos\theta\sin\theta}$.

If we don't get $c$, then let's take $l_4$ to be the line:

$$y=\frac{\sqrt{1-a^2}-\sqrt{1-b^2}}{2\cos\theta}-1.$$

Note that this $l_4$ does cross any one of lower-left sub-family of circles because of the following:

$$\frac{-\sqrt{1-a^2}-\sqrt{1-b^2}}{2\cos\theta}+1>\frac{\sqrt{1-a^2}-\sqrt{1-b^2}}{2\cos\theta}-1 ⇔ \cos\theta>\frac{\sqrt{1-a^2}}{2}.$$

Since we do get $c$, we can calculate $k$.

(ii) When $\omega<\theta<\pi/2$, let's take $l_3$ to be the line:

$$x=\frac{\sqrt{1-b^2}-\sqrt{1-a^2}}{2\sin\theta}+1.$$

Note that this $l_3$ does cross any one of upper-right sub-family of circles because of the following:

$$\frac{\sqrt{1-b^2}-\sqrt{1-a^2}}{2\sin\theta}+1>\frac{\sqrt{1-a^2}+\sqrt{1-b^2}}{2\sin\theta}-1 ⇔ \sin\theta>\frac{\sqrt{1-a^2}}{2}.$$

If we get $c$, we can take a positive root (there's exactly one positive root) in $(\star\star)$ as $h$, because this $l_3$ never crosses the lower-left sub-family of circles: this is because for any $d_1>d_2$,

$$\frac{\sqrt{1-b^2}-\sqrt{1-a^2}}{2\sin\theta}+1>\frac{\sqrt{1-a^2}-\sqrt{1-b^2}}{2\sin\theta}+1.$$

Then, let's calculate $k=\frac{a^2-b^2}{4h\cos\theta\sin\theta}$.

If we don't get $c$, then let's take $l_4$ to be the line:

$$x=\frac{\sqrt{1-a^2}-\sqrt{1-b^2}}{2\sin\theta}-1.$$

Note that this $l_4$ does cross any one of lower-left sub-family of circles because of the following:

$$\frac{\sqrt{1-a^2}-\sqrt{1-b^2}}{2\sin\theta}-1<-\frac{\sqrt{1-a^2}-\sqrt{1-b^2}}{2\sin\theta}+1 ⇔ \sin\theta>\frac{\sqrt{1-a^2}}{2}.$$

Since we do get $c$, we can calculate $k$.

I hope I'm not mistaken.

Edit $6$: Just an idea.

I guess that there exists a line (let's call this $L$) which satisfies the following several conditions. If exists, it can be taken as $l_3$.

1. If we rotate $l_1$ about the point $(\frac{\sqrt{a^2-b^2}}{4\sin\theta}, \frac{\sqrt{a^2-b^2}}{4\cos\theta})$ by some angle, then we'll get $L$. Note that this point is the center of the smallest circle of the upper-right sub-family.

2. $L$ crosses every circle of the upper-right sub-family.

3. $L$ never crosses any circle of the lower-left sub-family.

4. The length of each chord cut by $L$ is different from each other.

It might be difficult to give an actual example as $L$, but it is likely that there would exist such $L$.