In base 10, $\sqrt{81} = 8 + 1 = 9$. It turns out that 81 is the only number in base 10 that has this property. I wanted to find out if there are other numbers with this property in other bases. Mathematically, for a given base $b$, I'm looking for numbers $n$ with digits $d_i$ in base $b$ such that

$$ \sqrt{\sum^{\infty}_{i=0} d_i\cdot b^i} = \sum^{\infty}_{i=0} d_i $$

I wrote this code to brute force the solutions in any given base. I've also uploaded the set of solutions for the first 5000 bases here. Here I don't consider 0 and 1 to be solutions

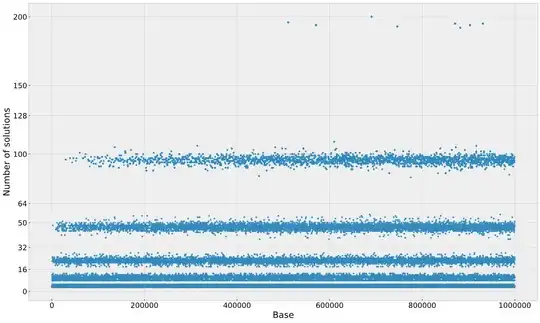

The pattern arises when I tried [plotting the number of solutions for 1 million bases (plot only includes at most 5000 data points from each strip $[2^n, 2^{n+1}]$):

There are distinct gaps in the data that appears to roughly correlate with powers of 2? Furthermore, the smallest base of each "strip" are bases 7, 31, 211, 2311, 30031, 510511, which are Euclid numbers, these bases have 5, 10, 21, 48, 96, and 196 solutions respectively. I've verified that base 9699691 has 397 solutions and base 223092871 has 784 solutions. Here's the data in numpy.array format

I'm not quite sure what to make of this. On the one hand, the powers of two-like pattern makes me suspect that it could stem from a floating point precision error or a bug in the code. On the other, the manner in which the powers of two present themselves feels atypical for a computational error.

My question is does this pattern actually exist, and if so I would appreciate any insight into why such a pattern arises from this problem.

Edit: It also appears that $(b-1)^2$ is always a solution as proven in the comments.

Edit 2:

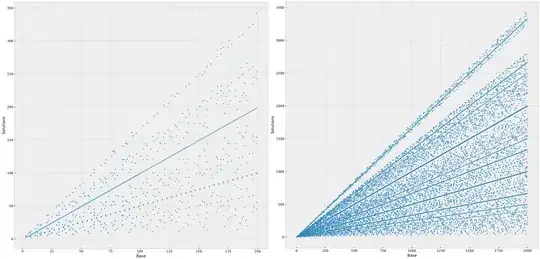

I plotted out the solutions $\sqrt{n}$ against the base $b$, and there appears to be rays with varying slopes: