The open sets in a quotient topology are precisely those for whom the inverse image under the quotient map is open.

That is if $(X,\tau)$ be my topological space then under the equivalence relation $\sim$ . And if $q:X\to X/\sim$ be the quotient map such that $q(x)=[x]$. The quotient space $(X/\sim,\tau')$ has the topology $\tau'$ such that

$\tau'=\{U:q^{-1}(U)\in \tau\}$. That is how the quotient topology is constructed such that the quotient map is continuous.

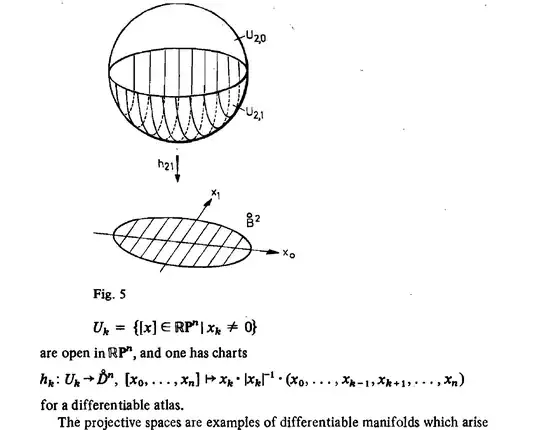

The real projective space is usually defined as follows:-

$\mathbb{RP}^{n}=\frac{\mathbb{R}^{n+1}\setminus\{0\}}{\sim}$. The equivalence relation is $x\sim y\iff x=\lambda y$ for some $\lambda\in\mathbb{R}\setminus\{0\}$.

That is every vector along the vector $x$ is equivalent to it. The stretching or compressing the vector $x$ gives you the sane equivalence class.

A bit of notation now . When I write parantheses I mean the coordinates in the euclidean space. When I write $[.]$ , I mean the elements in the quotient space.

Now this structure is homeomorphic to $S^{n}/\sim'$

Where this $\sim'$ is given by identifying antipodal points as being in the same equivalence class. That is basically what is meant by $x\sim' -x$. (Think about it , if you view the sphere inside $\mathbb{R}^{n+1}$ then two points are equivalent iff $\lambda=1$ or $\lambda=-1$. That is the diamtetrically opposite points are same. The homeomorphism being induced by the universal property.(This should remind you of the first isomorphism theorem in Group Theory). Namely you map $x\in\mathbb{R^{n+1}}\setminus\{0\}$ to $[\frac{x}{|x|}]\in S^{n}/\sim'$ . This map then induces the homeomorphism from $\mathbb{RP}^{n}\to S^{n}/\sim'$.

Now consider the the open set $\bar{U_{i}}\subset\mathbb{R^{n+1}}\setminus\{0\}$

such that $\bar{U_{i}}=\{(x_{1},x_{2},...x_{n+1})\in\mathbb{R^{n+1}}\setminus\{0\}\,: x_{i}\neq 0\}$.

Then you look at the image of this set $q(\bar{U_{i}})=U_{i}$. You need to use surjectivity of quotient map and the properties of quotient topology to see that $U_{i}$ is indeed open in $\mathbb{RP}^{n}$ under the quotient topology.

Then you cover $\mathbb{RP}^{n}$ by these $n+1$ open sets $U_{i}$ .

Then you define $\bar{\phi_{i}}:\bar{U_{i}}\to\mathbb{R}^{n}$ by

$\displaystyle\bar{\phi_{i}}(x_{1},x_{2},..,x_{i},...x_{n},x_{n+1})=(\frac{x_{1}}{x_{i}},\frac{x_{2}}{x_{i}},...\hat{x_{i}},..\frac{x_{n+1}}{x_{i}})$ . Where the $\hat{x_{i}}$ means that the i-th coordinate is missing. It's just a way of writing. If it confuses you , think of it as $\displaystyle(\frac{x_{1}}{x_{i}},\frac{x_{2}}{x_{i}},...\frac{x_{i-1}}{x_{i}},\frac{x_{i+1}}{x_{i}},..\frac{x_{n+1}}{x_{i}})$.

Then again using the universal property we get that the quotient map induces the map

$\phi_{i}:U_{i}\to\mathbb{R}^{n}$

given by $\displaystyle\phi_{i}([x_{1},x_{2},...x_{n+1}])=(\frac{x_{1}}{x_{i}},...\hat{x_{i}},...\frac{x_{n+1}}{x_{i}})$

This map is clearly continuous(because $\frac{1}{x}$ is continuous). And it is bijective because we can actually compute the inverse.

$\phi_{i}^{-1}(x_{1},x_{2},...x_{n})=[x_{1},x_{2},...x_{i-1},1,x_{i},x_{i+1},..x_{n}]$.

You can easily verify the well definedness of these maps and the bijectivity should not be hard to see either. The point is that these $\phi_{i}$'s are homeomorphisms. (Actually you only need to verify bijectivity . The continuity part follows from the construction of quotient topology itself and thus by the universal property.)

Then I have charts $(U_{i},\phi_{i})$ of my real projective space. Now I need only verify the smooth compatibility.

Indeed if $\phi_{i},\phi_{j}$ are different charts . We get,

$$\displaystyle\phi_{j}\circ\phi_{i}^{-1}(x_{1},x_{2},...x_{n})=\phi_{j}[x_{1},x_{2},...x_{i-1},1,x_{i+1},...x_{n}]=\\(\frac{x_{1}}{x_{j}},...\frac{x_{j-1}}{x_{j}},\frac{x_{j+1}}{x_{j}},...\frac{x_{i-1}}{x_{j}},\frac{1}{x_{j}},\frac{x_{i}}{x_{j}},\frac{x_{i+1}}{x_{j}}...\frac{x_{n}}{x_{j}})$$

And this is a smooth map as again $\frac{1}{x}$ is a smooth map in any deleted neighbourhood of the origin.

Thus these $\{(U_{i},\phi_{i})\}_{i=1}^{n}$ gives me a smooth structure on $\mathbb{RP}^{n}$ and thus they give you a maximal smooth atlas containing them.

You can then actually prove that the map $x\mapsto [\frac{x}{|x|}]$ induces a diffeomorphism from $\mathbb{RP}^{n}\to\mathbb{\frac{S^{n}}{x\sim -x}}$

I hope this answers your question as to how to show that it is a differentiable manifold. (I have excluded the proofs for Hausdorffness and Second Countability). You can look it up .

As to how these charts look like, you should really see the picture in your book. Then try to do this for the unit circle in $\mathbb{R}^{2}$. After that I think it will be clearer to you. As always, it is hard to actually vizualize quotiented things . Sometimes , the algebraic intuition is more helpful than the geometric intuition.

PS:- You should read a little about the quotient topology and the universal property to make life easier. Otherwise actually trying to justify continuity and stuff become unecessarily laborious.