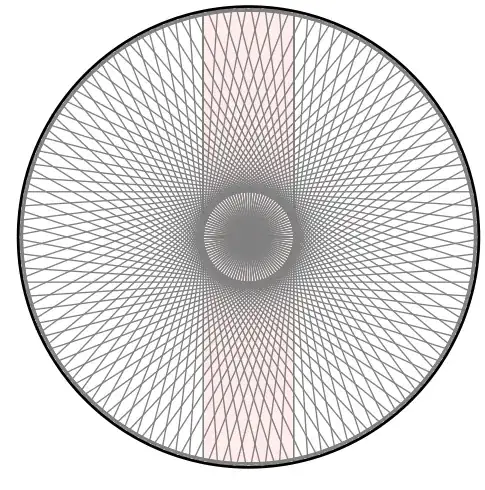

I came here from this question, which I found a simple and concise proof for the following:

Consider any simply connected shape on a 2D Euclidean plane. If, for any line that intersects this shape, the reflection of the parts of the boundary that lie on one side of the line do not intersect the parts of the boundary that lie on the other side, then the shape must be a circle. Here, two curves intersect means that there is at least one point that lies on both curves, and at least one point that lies on one curve but not another. (So completely overlapping does not count as intersecting.)

(I don't understand why that question got closed. Last time I checked, the consensus seems to be that these are related but different questions. If anyone can re-open it, please do.

But anyway, here I'm going to reduce this problem to that one.)

If it's true that the reflection of the half can't intersect with the other half here as well, then we're done. Is it possible that the reflection intersects with the other half while the shape remains convex? Unfortunately, it's true. A simple example is matching the vertex of a rectangle to the opposite one on the diagonal. The resulting shape is still convex, although the boundaries intersect.

But, notice that, if you move the line slightly above, it'll no longer be convex. So, the only remaining task is, to make this argument rigorous. (Which takes way more effort than proving the previous statement, though.)

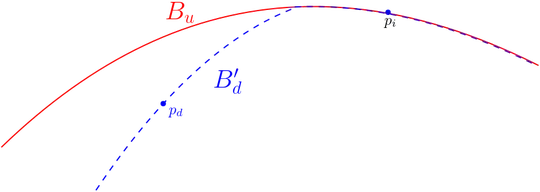

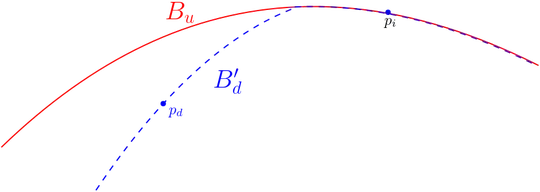

So, let's suppose that: There is a line, $L$, that cuts the boundary into two parts, $B_u$ and $B_d$, the upper and lower parts. The reflection of $B_d$, $B'_d$, intersects with $B_u$, thus there must be a point $p_i$ which lies on both $B_u$ and $B'_d$, and another point $p_d$ which is on $B'_d$ but not on $B_u$.

Due to symmetry, w.l.o.g, suppose the line $L$ is horizontal, and suppose $p_d$ is to the left of $p_i$ and under $B_u$.

Here $B'_d$ and $B_u$ may intersect at a single point $p_i$, or they may overlap on a curve where $p_i$ lies on. It doesn't matter which case it is.

Here $B'_d$ and $B_u$ may intersect at a single point $p_i$, or they may overlap on a curve where $p_i$ lies on. It doesn't matter which case it is.

Now, we want to show that, if we move the line $L$ slightly above, then the reflection of $B_d$ will also move slightly above, which will cause the shape to be non-convex.

The following is just the thought process which is not rigorous, but it shows the direction.

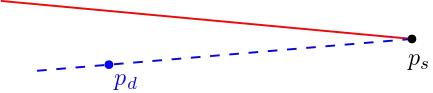

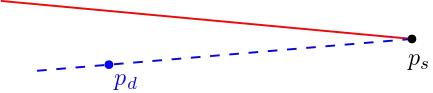

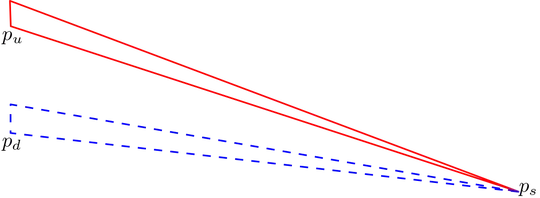

To do that, consider the point where the two curves splits. If we zoom in enough, the boundaries should appear linear, like this:

Then, if we move the blue dotted line a little bit above, it will intersect the red solid line, which results in the shape being concave.

So, is that true that if we zoom in enough, the curve appears linear?

Now, we introduce the concept of "left tangent line".

First, we prove that, for any point $p$ on one of the curves, for any angle $\delta$, there exists a distance $d$ and an angle $\theta$ such that, for any point $p_1$ that's to the left of $p$ which is less than $d$ from $p$ horizontally, the line that connect $p$ and $p_1$ must make an angle within $[\theta,\theta+\delta]$ with the $-x$ axis.

Translation to plane words: if we zoom in enough, the curve should appear to be almost linear (If we connect any two points, the angle of the slope of the line should be within a small interval).

The proof is actually very simple. Suppose it's not true. There's an angle $\delta$ such that there's no distance that satisfies this condition. Then, we choose an arbitrary point, $p_1$, to the left of $p$. Suppose the angle of the line through $p_1$ and $p$ is $\theta$. Because the shape is convex, the angle between $-x$ axis and the line that connects $p$ and any point $q$ on the curve between $p_1$ and $p$ must be greater than $\theta$. Then, there must be a point $p_2$ where the line through $p_2$ and $p$ makes an angle that is at least $\theta+\delta$. Then, we must be able to find another point $p_3$, which makes an angle $\theta+2\delta$. We can keep doing that. Since $\delta$ is finite, if we do this enough times, the line will be rotated for more than $\pi$, so it's impossible that the point is to the left of $p$, contradiction.

So, we proved that the left slope, thus the left tangent line, must exist, which does not necessarily equal the right slope or right tangent line, which is obvious considering the vertex of a polygon.

Now, we are able to limit the tangent line to an arbitrarily small angle. How do we proceed?

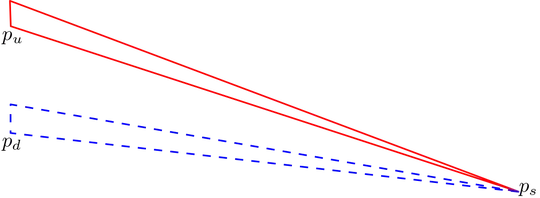

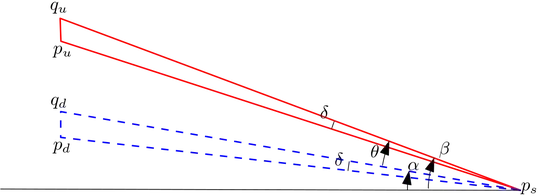

Basically, for a small region to the left of the point $p_s$ where the two curves split, we are able to limit the upper curve to be inside the solid triangle, and the lower curve inside the dashed triangle.

Basically, for a small region to the left of the point $p_s$ where the two curves split, we are able to limit the upper curve to be inside the solid triangle, and the lower curve inside the dashed triangle.

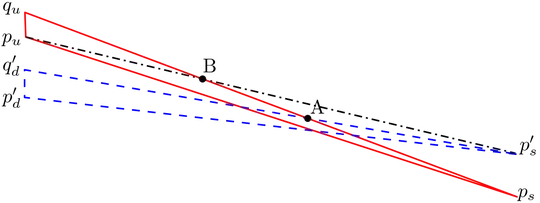

If the two triangles don't intersect, then we can move the lower triangle a little bit above, so that they intersect:

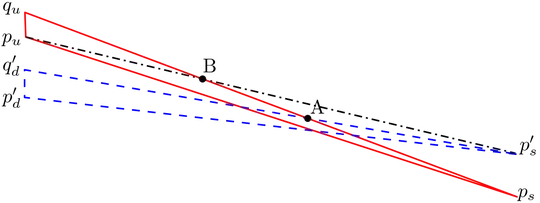

Suppose the line that connects $q'_d$ and $p'_s$ intersects with the line that connects $q_u$ and $p_s$ at $A$, and the line $p_u - p'_s$ and $q_u - p_s$ intersect at $B$.

Since $p_u$ is on the curve, every point below the line $p_u - p'_s$ (and above horizontal line $L$) must be inside the shape, because it must remain convex. But the upper boundary is inside the solid triangle $q_u p_u p_s$, and the reflection of the lower boundary is inside the dashed triangle $q'_d p'_d p'_s$. Thus, every point inside the triangle $ABp'_s$ is not inside the shape. Contradiction.

Now, we still have one assumption: We can find a small enough distance such that the two triangles don't intersect. Unfortunately, this is not always true. It's possible that the two curves have the same tangent line at $p_s$, i.e, they're tangent at $p_s$.

But notice that: we don't really need to use the point where the two curves split. We can move the reflected curve up and down. If that point doesn't work, we can move the curve and let them intersect at another point, where they are not tangent.

So, we want to show that, there exist an $x$ coordinate $x_0$, such that the corresponding points $A_u$ and $A_d$ with $x$-coordinate $x_0$ on the curves $B_u$ and $B'_d$ respectively, have different left slope.

Assume that this is not true: For any $x$ coordinate, the two points on the two curves with this $x$ coordinate has the same left slope. Then we can just start from the point where they intersect, and every pair of points to the left of it on the two curves must overlap. Thus the two curves to the left of the intersecting point must overlap, contradicting the fact that there exist a point that is to the left of the intersecting point, and lies on one curve but not the other.

(Update: Here it's missing a special case: the intersecting point $p_s$ lies on a vertical part of the curves. Example: We're folding a rectangle along one of its edges. So, to make the argument work, we must add another condition: If the two curves only intersect at a vertical part of them, then consider the line that's parallel to it which cuts the shape into two equal areas, as I did in the answer to the other question. Then, under this condition, if they still intersect, they must intersect at a different point that's not on a vertical part of the curves, because otherwise, if the two curves still only intersect on the vertical part, the boundary must overlap completely, or the shape is not convex. This implies that the shape must be symmetric w.r.t this line, which reduces to the result of other question.)

Now it becomes clear how we construct the proof.

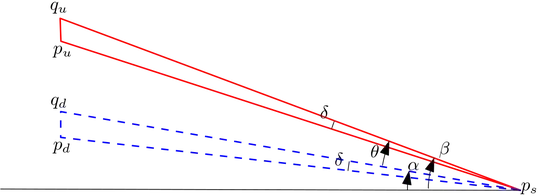

There exist a pair of points $A_u$, $A_d$ with the same $x$ coordinate $x_0$ that lies on the two curves and have different left slopes. Suppose the difference in the angle of the tangent lines is $\theta$. Next, we want to make sure that the two triangles don't overlap, thus we choose an angle $\delta<\theta$, and there must exist a distance $d_u$ such that any point on $B_u$ that has $x$ coordinate within $[x_0-d_u, x_0)$ must satisfy that the line connecting it and $p_u$ makes an angle within $[\alpha,\alpha+\delta]$ with the $-x$ axis. There must exist a distance $d_d$ for the reflected lower curve $B'_d$ as well, and a corresponding $\beta=\alpha-\theta$. We choose the minimum of the two distances, $d$.

Then, we move the line $L$ vertically by half of the vertical distance of $A_u$ and $A_d$, so that they overlap afterwards. Let's call the point $p_s$.

Now the situation is just as before, but we have guaranteed that the two triangles don't overlap.

Suppose the vertical distance between $p_u$ and $q_d$ is $h$. Moving the folding line $L$ above by $\frac{h}{4}$ will result in the reflected lower curve rising by $\frac{h}{2}$, thus the two triangles must intersect as shown in the figure above, thus causing the shape to be concave.

Since the reflected lower boundary can't intersect with the upper boundary, it reduces to the question that I linked to in the beginning. Thus the boundary must be a circle (the shape is a disk). The proof is complete.