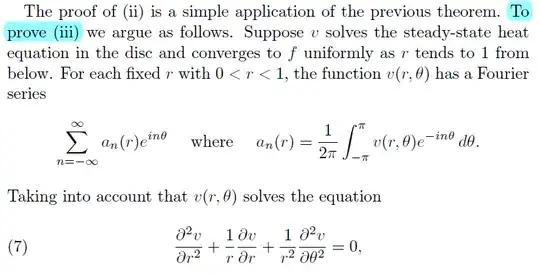

We're swapping the derivatives with respect to $r$ with the integral. We do exactly what the text tells us: multiply $(7)$ by $e^{-in\theta}$, then integrate with respect to $\theta$, and then divide the whole thing by $2\pi$. Then, we use split up the sum into three pieces and use Leibniz's integral rule on the first two terms:

\begin{align}

0&=\frac{1}{2\pi}\int_{-\pi}^{\pi}\left(\frac{\partial ^2v}{\partial r^2}+

\frac{1}{r}\frac{\partial v}{\partial r}+\frac{1}{r^2}\frac{\partial^2v}{\partial \theta^2}\right)e^{-in\theta}\,d\theta\\

&=\frac{d^2}{dr^2}\left(\frac{1}{2\pi}\int_{-\pi}^{\pi}v(r,\theta)e^{-in\theta}\,d\theta\right)\\

&+ \frac{1}{r}\frac{d}{dr}\left(\frac{1}{2\pi}\int_{-\pi}^{\pi}v(r,\theta)e^{-in\theta}\,d\theta\right)\\

&+ \frac{1}{r^2}\left(\frac{1}{2\pi}\int_{-\pi}^{\pi}\frac{\partial^2v}{\partial \theta^2}e^{-in\theta}\,d\theta\right)\\

&=a_n''(r)+\frac{a_n'(r)}{r}+\frac{1}{r^2}\left((-1)^2\frac{1}{2\pi}\int_{-\pi}^{\pi}v(r,\theta)\frac{d^2}{d\theta^2}(e^{-in\theta})\,d\theta\right)\\

&=a_n''(r)+\frac{a_n'(r)}{r}+\frac{1}{r^2}(-n^2a_n(r))

\end{align}

The $(-1)^2$ terms is due to integration by parts twice; also due to periodicity of $v$ with respect to $\theta$, there are no boundary terms coming from the integration by parts. The $(-n^2)$ comes from differentiating the exponential twice (we bring down the factor $(-in)^2=-n^2$). This proves that $a_n$ satisfies the ODE given by equation $(8)$.

As much as I would like to appeal to Lebesgue's DCT to justify the interchange of derivatives with respect to $r$ and the integral, I certainly understand you wanting a more elementary argument, though I find it surprising that this isn't justified somewhere in Stein and Shakarchi's book. Below is a simple enough statement and proof of Leibniz's integral theorem:

Leibniz's Differentiation Theorem:

Let $f:[a,b]\times [c,d]\to\Bbb{R}$ be a continuous function with $\partial_1f\equiv \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}:[a,b]\times [c,d]\to\Bbb{R}$ also continuous. The function $F:[a,b]\to\Bbb{R}$ defined by

\begin{align}

F(x)&:=\int_c^df(x,t)\,dt

\end{align}

is continuously differentiable, and for each $x\in [a,b]$, we have

\begin{align}

F'(x)&=\int_c^d\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}(x,t)\,dt

\end{align}

Some remarks: this is of course far from general, but this is usually sufficient when dealing with many of the simple examples, and this only requires basic single-variable Riemann integrals, the single-variable mean-value theorem for derivatives, and the fact that continuity on a compact set ($[a,b]\times [c,d]$) implies uniform continuity. Also, one typically defines derivatives for functions defined on open sets, but here since we're dealing with partial derivatives on a closed rectangle, this is easy to define: we're just requiring that for each $t\in [c,d]$, the function $f(\cdot, t):[a,b]\to\Bbb{R}$, $x\mapsto f(x,t)$ is differentiable, with appropriate one-sided derivatives interpretation at the endpoints $a$ and $b$.

Also, clearly, the more continuous partials we have, the more times we can differentiate under the integral sign (this is a simple induction), so in your case, you're assuming $v$ is $C^2$, so you can certainly apply this result twice. Now onto the proof.

Proof:

Fix $x_0\in [a,b]$. Let $\epsilon>0$, and choose a corresponding $\delta>0$ using uniform continuity of $\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}$ on $[a,b]$. Then, for any $h\in\Bbb{R}$ with $0<|h|<\delta$ and $x_0+h\in [a,b]$, we have

\begin{align}

\left|\frac{F(x_0+h)-F(x_0)}{h}-\int_c^d\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}(x_0,t)\,dt\right| &\leq \int_c^d\left|\frac{f(x_0+h,t)-f(x_0,t)}{h}-

\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}(x_0,t)\right|\,dt\\

&=\int_c^d\left|\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}(\xi_{x_0,h,t},t)-

\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}(x_0,t)\right|\,dt\\

&\leq \int_c^d\epsilon\,dt\\

&=\epsilon(d-c)

\end{align}

Note that in the middle, for each $t\in [c,d]$, we used the mean-value theorem on the function $f(\cdot,t)$ on the interval joining $x_0$ and $x_0+h$ to find some point $\xi_{x_0,h,t}$ (note that this depends on $x_0,h$ and also $t$, which is why this proof utilizes uniform continuity) in the open interval interval between $x_0+h$ and $x_0$. Now, since $\epsilon>0$ was arbitrary, and the point $x_0\in [a,b]$ was arbitrary, this shows $F$ is a differentiable function with the derivative as stated.

Finally, $F'$ is continuous because it is the integral of a continuous function on a compact rectangle.

For the sake of completeness, here's the theorem about continuity of integrals:

Continuity Theorem:

If $K$ is a compact metric space and $g:K\times [c,d]\to\Bbb{R}$ is continuous (hence uniformly continuous), then the integrated function $G:K\to\Bbb{R}$, $G(x):=\int_c^dg(x,t)\,dt$ is (uniformly) continuous on $K$.

The proof is a two-liner. Given $\epsilon>0$, choose $\delta>0$ according to uniform continuity of $g$ on the compact metric space $K\times [c,d]$. Then, for any $x,y\in K$ with distance at most $\delta$, we have

\begin{align}

|G(x)-G(y)|&\leq\int_c^d|g(x,t)-g(y,t)|\,dt\leq \epsilon(d-c),

\end{align}

so arbitrariness of $\epsilon$ shows $G$ is uniformly continuous.