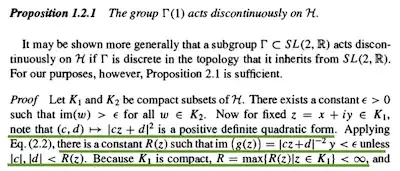

I am reading the proof of the following theorem in Bump's Automorphic Forms and Representations. However, I don't understand the first part of the proof.

It is clear that $(c,d)\mapsto |cz+d|^2$ is a positive definite quadratic form. Then equation 2.2 gives $\operatorname{im}(g\cdot z)=\frac{\operatorname{im} z}{|cz+d|^2}$, so we want $|cz+d|^2$ to be small. But why does it follow that there exists such a constant $R(z)$? Moreover, in the last line, he seems to use that $z\mapsto R(z)$ is continuous. Why is this true?

Any help is appreciated :)

As an aside, why is such an action called "discontinuous"? I have seen some books call this "properly discontinuously" or in French "propre". Isn't this terminology contradictory ? The action of $SL_2 \mathbf{Z}$ on $\mathbf{H}$ is "continuous" in the sense that $SL_2\mathbf{Z}\times \mathbf{H}\to \mathbf{H}$ is continuous, right?