Let $X$ be a space and $\{A_\alpha:\alpha \in I\}$ a family of connected subsets of $X$ for which $\bigcap\limits_{\alpha \in I} A_\alpha \ne \emptyset$.

Let first modify the notation a little bit. We modify $\bigcup \mathscr{F}$ in the question into $Y = \bigcup\limits_{\alpha \in I} A_\alpha$.

We will use this Theorem 1 to prove that $Y$ is connected: (For the curious minds, the proof of Theorem 1 itself is outlined below.)

$Y$ is disconnected if and only if there exist open sets $U$ and $V$ in $X$ such that:

$U \cap Y \ne \emptyset$; $V \cap Y \ne \emptyset$; $U \cap V \cap Y = \emptyset$; $Y \subset U \cup V$.

Note that $U$ and $V$ are not necessarily disjoint.

Suppose that $U$ and $V$ are open sets in $X$ for which $U \cap Y \ne \emptyset$; $U \cap V \cap Y = \emptyset$; $Y \subset U \cup V$. We will show that $V \cap Y = \emptyset$ thus proving that $Y$ is connected.

As $U \cap Y \ne \emptyset$, so $U$ contains some points in $A_{\alpha'}$ for some $\alpha' \in I$. We know that $Y \subset U \cup V$ which means $A_{\alpha'}$ could be in both $U$ and $V$ as well. However, because $(U \cap A_{\alpha'}) \cap (V \cap A_{\alpha'}) = U \cap V \cap A_{\alpha'} \subseteq U \cap V\cap Y = \emptyset$, we know that if $A_{\alpha'}$ are in both $U$ and $V$, then it would be disconnected. As $A_{\alpha'}$ is connected by definition, $A_{\alpha'}$ must be either in $U$ or $V$, so $A_{\alpha'} \subset U$.

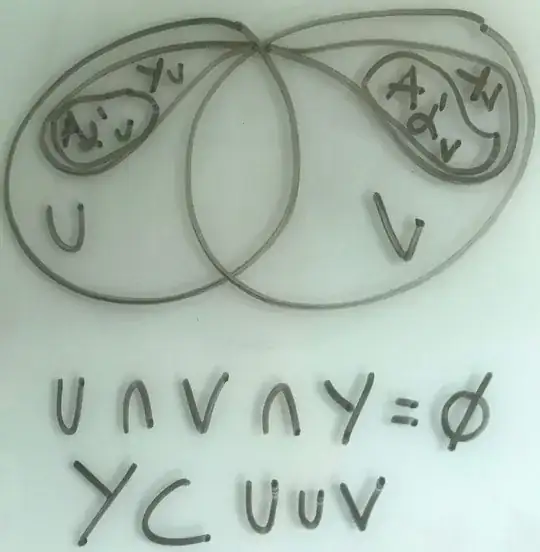

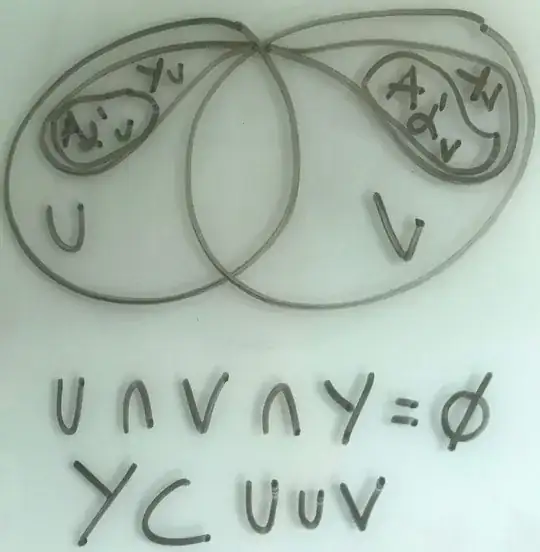

Refer to this picture for a clearer visualization of when both $A_{\alpha'}$ are present in both $U$ and $V$. This situation leads to the disconnection into $A_{{\alpha'}_U}$ and $A_{{\alpha'}_V}$:

If $b \in \bigcap\limits_{\alpha \in I} A_\alpha$, then $b$ must be in $A_{\alpha'}$, so $b \in U$. Thus U contains a point b in each $A_\alpha$, $\alpha \in I$. By the same reasoning above and as $A_\alpha$ is connected, then $A_\alpha \in U$ for each $\alpha \in I$.

Thus:

$Y = \bigcup\limits_{\alpha \in I} A_\alpha \subset U$.

Which leaves nothing remaining for $V$, so:

$V \cap Y = \emptyset$.

Proof of Theorem 1:

Suppose that Y is disconnected. Then there are non-empty open sets $A$ and $B$ in the subspace topology for $Y$ such that $Y = A \cup B$ and $A \cap B = \emptyset$. By the definition of relatively open sets, there must be open sets $U$ and $V$ in $X$ such that:

$A = U \cap Y$, $B = V \cap Y$.

So:

$U \cap V \cap Y = (U \cap Y) \cap (V \cap Y) = A \cap B = \emptyset$;

$Y = A \cup B = (U \cap Y) \cup (V \cap Y) \subset U \cup V$.

For the reverse implication:

$A \cap B = (U \cap Y) \cap (V \cap Y) = U \cap V \cap Y = \emptyset$;

$A \cup B = (U \cap Y) \cup (V \cap Y) = (U \cup V) \cap Y$, and since $Y \subset U \cup V$, $A \cup B = Y$.