Let $p$ be a prime such that $p \bmod 4 = 1$, so there exists some $i=\sqrt{-1}$ in $\mathbb{F}_p$. Furthermore, let $r \in \mathbb{N}$ be the radius of a circle such that there are $p-1$ lattice points on it. (The sums of squares function allows to compute such $r$.)

I think that for every lattice point $(x,y)$ there is a unique $z = x + iy$ in $\mathbb{F}_p$. Also, there is a generator $g$ in $\mathbb{F}_p$ such that $g^\alpha$ traverses the lattice points in the order given by their angle on the circle.

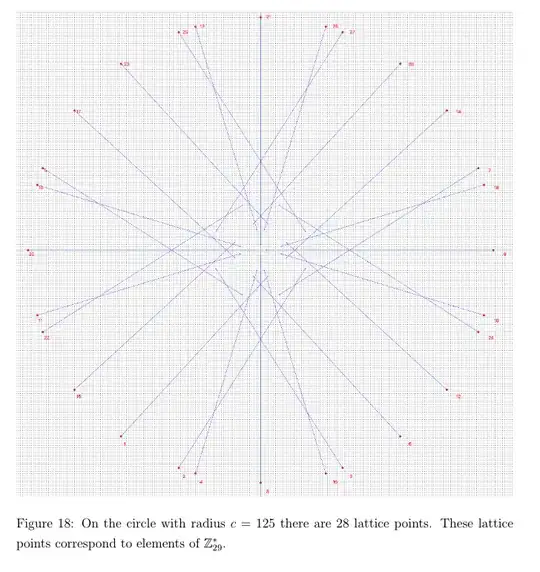

Here's an example with $g=2$:

(The line segments in the picture above point to $(x \bmod p)$ and $(y \bmod p)$. They describe a circle of radius $(r \bmod p)$ in the finite plane $\mathbb{F}_p \times \mathbb{F}_p$.)

Is there any literature about that phenomenon?

Can you prove the order of points fits the order given by $g^\alpha$?

Here are questions related to that topic:

Another interesting observation is that this relation between pythagorean triples and field elements allows to map elements of finite fields to rational points on the unit circle.

(In simple terms: what looks like a circle here is actually $q$ different squares.)

– Robin May 07 '21 at 05:42