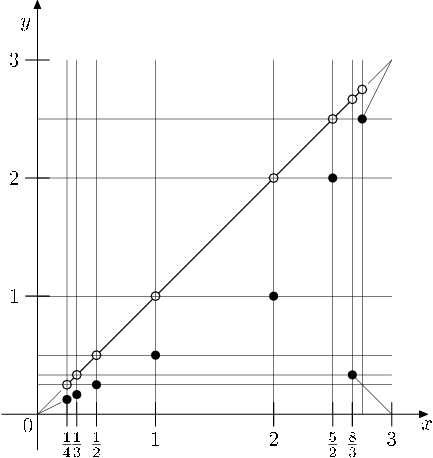

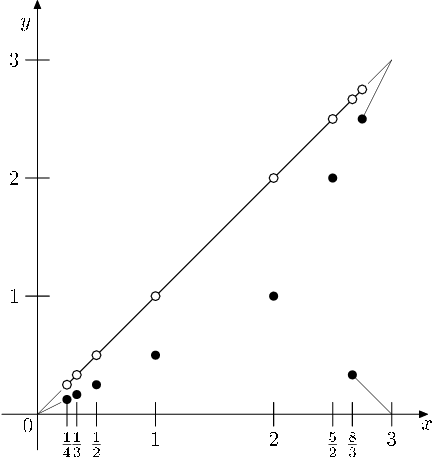

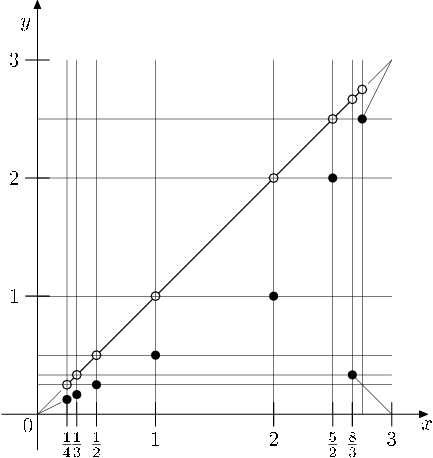

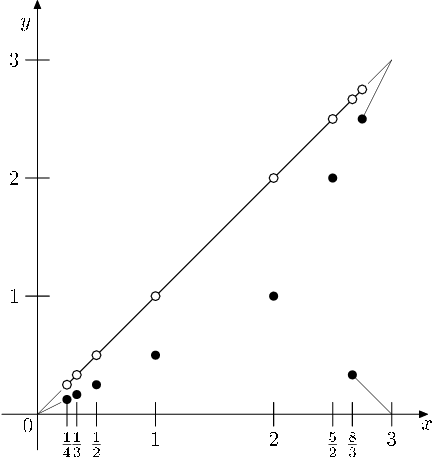

I think the following could be a counterexample.

Let us define $f \colon [0,3] \to [0,3]$ as follows:

$$

\begin{align}

f\left(\frac 1n\right)&=\frac1{2n}; \text{ for }n=1,2,3,\dots;\\

f\left(3-\frac1{2n-1}\right)&=\frac1{2n-1}; \text{ for }n=1,2,3,\dots;\\

f\left(3-\frac1{2n}\right)&=3-\frac1{n}; \text{ for }n=1,2,3,\dots;\\

f(x)&=x; \text{ if $x$ does not have the form $\frac1n$ or $3-\frac1n$}

\end{align}

$$

In other words, we are working only with points of the form $1/n$ and $3-1/n$ and we do not move other points. The points of the form $1/n$ are mapped to $1/(2n)$. So far we do not have anything mapped onto points of the form $1/(2n+1)$, so we use half of the points of the form $2-\frac1n$ to get something mapped onto them.

The function $f$ is bijective, it is continuous at $0$, but $f^{-1}$ is not continuous at $0$. (To see this just take $x_n=\frac1{2n+1}$ and notice that $x_n\to0$ and $f^{-1}(x_n)\to3$.)

The basic idea is very similar to general "Hilbert's hotel" idea, like here and in many other constructions of bijections. I hope that, at least to some extent, I managed to capture the construction in the following picture, which might help you ti visualize this example.

EDIT: I've added one more version of the picture. The dotted lines might make easier to see which of the "full" and "empty" circles have the same x-coordinates/the same y-coordinates.