Assume that $ΔABC$ is an isosceles triangle with base of length 3, and sides of length 4.

The main question is:

What is the area of the largest equilateral triangle that can be inscribed in $ΔABC$?

And, if we find a value, how can we prove that it's the biggest possible value and there exists no other equilateral triangle inscribed in $ΔABC$ with a larger area?

(I know that for an equilateral triangle, having the largest area is the same as having the largest side length, but the main question is to find the numerical value of the largest area)

What I have done so far:

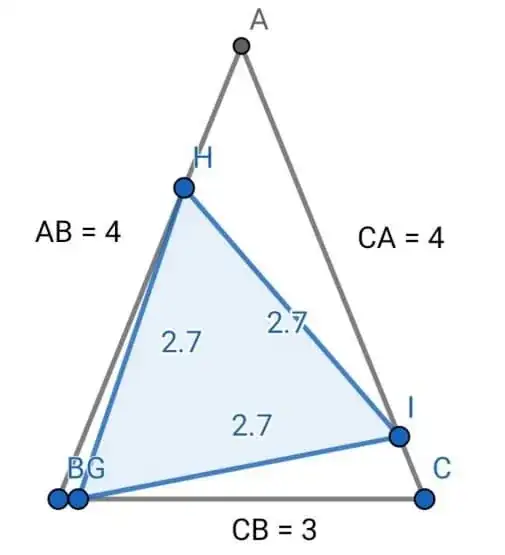

- I tried to play around with shapes in GeoGebra, in hope of finding an idea to solve the problem (something like using rotations, etc.). but it wasn't that helpful.

A problem is that the values on the image are not accurate, so I need a mathematical proof rather than only drawings, to show that a value is the largest one.

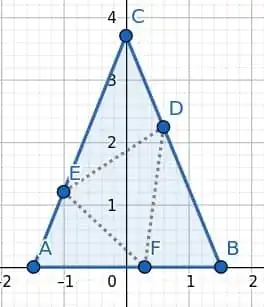

- I tried to draw the isosceles triangle on a xy-plane:

(The height of the triangle is $\frac{\sqrt{55}}{2} \approx 3.7$ using the Pythagorean theorem)

First, I calculated line equation for each edge, then I chose 3 arbitrary points $P_1$ and $P_2$ on the sides (shown with $E$ and $D$ on the image) and $P_3$ on the base (point $F$ in the figure) with coordinates $(x_1, y_1)$, $(x_2, y_2)$ and $(x_3, y_3)$ respectively. Then I tried to rewrite $y_1$ and $y_2$ using $x$'s and the line equations. Then I used the formula for Euclidean distance and inserted $x$'s and $y$'s inside the formula and put each pair of distances in equation (since they are side lengths of an equilateral triangle). Eventually, I started to solve the equations and continue that way to establish a relation between the coordinates, however, it wasn't successful, or at least I wasn't able to derive any result.

Thanks in advance!