This nice question led me to some thoughts, which I am going to write down in this answer.

NOTATION. The letter $C$ will always denote an irrelevant positive constant, whose value can change from line to line.

We are concerned here with the Gagliardo seminorms, which I will denote by $\dot{H}^s(\mathbb R^d)$ in compatibility with LL3.14’s answer, and which can be defined in two equivalent ways (see also this answer);

$$

\lVert f\rVert_{\dot{H}^s}^2:=\int_{\mathbb R^d} \lvert \xi \rvert^{2s}\lvert \hat{f}(\xi)\rvert^2\, d\xi =C\iint_{\mathbb R^d\times \mathbb R^d} \frac{\lvert f(x+y)-f(x) \rvert^2}{\lvert y \rvert^{d+2s}}\, dxdy.$$

Here $\hat{f}$ denotes the Fourier transform. We let

$$

\omega_f(y):=\int_{\mathbb R^d} \lvert f(x+y)-f(x)\rvert^2\, dx,\quad\text{ so that }\quad \lVert f \rVert_{\dot{H}^s}^2=C \int_{\mathbb R^d}\frac{\omega_f(y)}{ \lvert y \rvert^{d+2s}}\, dy. $$

The heuristic emerging from these formulations is that, for $f\in L^2$, the seminorm $\lVert f\rVert_{\dot{H}^s}^2$ is finite if and only if $\omega_f$ decays sufficiently fast at $0$, which happens if and only if $\hat{f}$ decays sufficiently fast at infinity.

In what follows, we will consider $f=\chi_E$ for some $E\subset \mathbb R^d$. In particular, we let $B$ denote the unit ball. In the nice answer of LL 3.14, the seminorm $\lVert \chi_B\rVert_{\dot{H}^2}$ is studied via the explicit decay rate of $\hat{\chi_B}$. Here we will perform the same analysis, but studying $\omega_{\chi_B}$ instead. This approach is perhaps more adherent to the OP’s initial thoughts.

Expanding the square, we see that

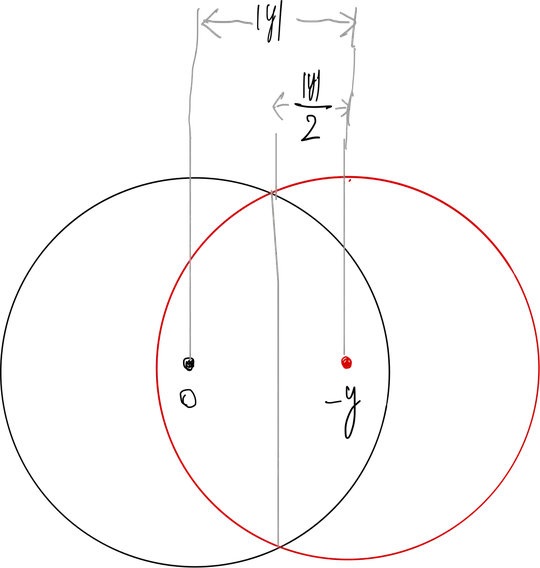

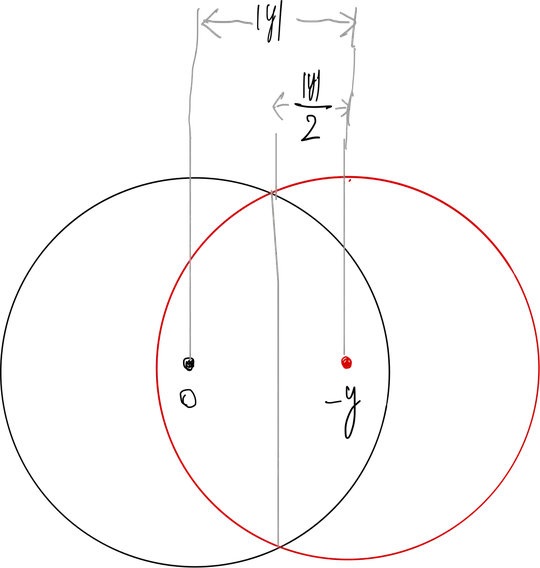

$$\tag{1}\omega_{\chi_B}(y)=2\lvert B\rvert -2\lvert B\cap (B-y)\rvert,$$ so we are reduced to study the measure of the intersection $B\cap (B-y)$. As the following crude picture shows,

such intersection is made of two equal spherical caps. Writing the volume of such caps as an integral, we obtain

$$

\lvert B\cap (B-y)\rvert = 2\lvert B^{d-1}\rvert \int_{\lvert y \rvert /2}^1 (1-z^2)^{\frac{d-1}{2}}\, dz.$$

Here $\lvert B^{d-1}\rvert $ denotes the volume of the $d-1$ dimensional ball, but it is not relevant for what follows. Indeed, we do not need an exact expression of $\lvert B\cap B-y\rvert$; an approximation to first order at $y\to 0$ will suffice. To compute such approximation, we note that

$$\lvert B\cap (B-y)\rvert \Big\rvert_{y=0}=\lvert B\rvert,$$

and it is clear from the integral that $\nabla_y \lvert B\cap (B-y)\rvert $ exists and it is not zero at $y=0$. We conclude that $$\lvert B\cap (B-y)\rvert =\lvert B\rvert -C\lvert y \rvert + O(\lvert y\rvert^2), $$

which, by (1), gives

$$\tag{2}

\omega_{\chi_B}(y)= C\lvert y \rvert + O(\lvert y \rvert^2).$$

This is all we need, as it immediately implies that

$$

\lVert \chi_B\rVert_{\dot{H}^s}^2= C \int_{\mathbb R^d} \frac{\omega_{\chi_B}(y)}{\lvert y\rvert^{d+2s}}\, dy <\infty \quad \iff \quad s<\frac12.$$

For an arbitrary $E\subset \mathbb R^d$ of finite measure, the result is that

$$\lVert \chi_E\rVert_{\dot{H}^s}^2<\infty \quad \Longrightarrow \quad s<\frac12.$$

This follows from the above by the symmetric rearrangement, which gives $\lVert \chi_E\rVert_{\dot{H}^s}\ge C\lVert \chi_B\rVert_{\dot{H}^s}$, as cleverly shown by LL 3.14.

I have tried to bypass the symmetric rearrangement. The above argument would push through if we could show that

$$

\omega_{\chi_E}(y)\ge C\lvert y \rvert + O(\lvert y \rvert^2), $$

but I couldn’t find a way to prove this. I don’t even know if this is true, actually.