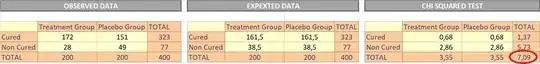

A clinical trial is done with 400 persons suffering from a particular disease, to find out whether a treatment is better than placebo. They are randomised to receive treatment or placebo (200 participants each). The outcome studied is how many get cured. The results are shown in the following 2x2 table:

\begin{array} {|r|r|} \hline \text{ } & \text{Treatment group} & \text{Placebo group}\\ \hline \text{Cured} & 172 & 151 \\ \hline \text{Not cured} & 28 & 49 \\ \hline \text{Total} & 200 & 200 \\ \hline \end{array}

The odds ratio calculated from this table is $1.99$. The objective now is to test the null hypothesis (odds ratio = 1) against the alternate hypothesis (odds ratio is not 1). Ludbrook's 2008 article describes an exact test for this scenario:

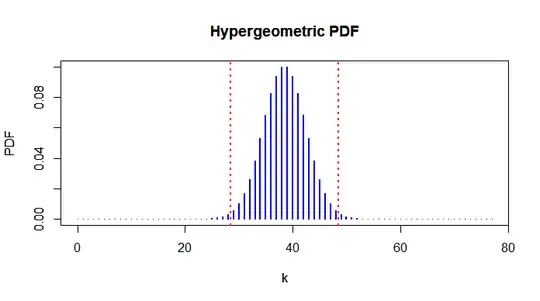

The formula for executing a two-sided randomization test, adapted to a 2x2 table with the constraint that the column totals are fixed (single conditioning), is:

P=(All tables for which the summary statistic is at least as extreme as that observed, in either direction)/All possible tables with the same column totals

I am a bit confused about what exactly it means. Does it mean I should form all possible tables with 200 treatment and 200 control participants, with each participant having a 50% chance of getting cured? Then there would be $2^{200} \times 2^{200}=2^{400}$ possible tables, each being equally likely. I would then calculate what fraction of these tables give an odds ratio equally or more extreme than the one I got experimentally, i.e. $1.99$. This would give me the p-value.

Is this the correct interpretation? If not, why?

If so, why the assumption of 50% cure rate? Why not 20%, 70%, 90%, or any other number?

(I would have contacted the author directly, but it turns out he is deceased. That is why I asked this question here.)

Reference

John Ludbrook, Analysis of 2 × 2 tables of frequencies: matching test to experimental design, International Journal of Epidemiology, Volume 37, Issue 6, December 2008, Pages 1430–1435, https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyn162