There is a winning strategy for Player A.

If Player A runs the optimal graph coloring algorithm with a specific modification they can win. The algorithm is described briefly here:

Algorithm $\text{Optimal-Color}(G)$

Initially all the vertices of the graph $G:=(V,E)$ are not colored

Initialize $All \leftarrow \{red, green, blue, yellow, black\}$, the set of all colors

$UncoloredDegree(v)$ is the number of neighbors of $v$ that are uncolored and $ColoredDegree(v)$ is the number of neighbors of $v$ that are colored

$Pick(G)$ is a function that picks the uncolored vertex $v$ with the highest $ColoredDegree(v)$. If two vertices have the same colored degree, the one with the higher degree is picked. A tie on degree is broken arbitrarily.

$ConflictColors(v)$ is the set of colors of colored neighboring vertices of $v$

$Color(v)$ is a function that colors the vertex $v$ using a color $c \in All \backslash ConflictColors(v)$

$Remove(v, G)$ is a function that removes the vertex $v$ from $G$ and deletes all incident edges of the vertex $v$ while retaining the neighbors of $v$ in the graph (The degrees of the vertices are updated automatically)

While $\exists v \in G$ having $UncoloredDegree(v) \gt 0$

a. $v = Pick(G)$

b. $Color(v)$

c. $G_v = \text{ the connected subgraph of $G$ }$.

d. While $G_v$ has an uncolored neighbor vertex

$n = Pick(G_v)$

$Color(n)$

End While

e. $Remove(v, G)$

End While

End Algorithm

Analysis. This is the standard graph coloring algorithm. After the highest degree vertex and its neighbors are colored, the vertex is removed, leaving its colored neighboring vertices in the graph. All its neighbors degree is now reduced by $1$. By definition the set of colors used for the neighbors of $v$ cannot conflict with the chosen color of $v$. Once $v$ is removed, its color is no longer in conflict, so in Step 5. it becomes available for potential use to color another node in a subsequent step.

Also, it does not matter which color from the non-conflicting colors is chosen in each step. This is the key reason why this is a winning strategy for Player A.

The algorithm terminates because at some point all nodes will be colored and the While Loop in Steps 8-9. stops.

Analysis of the adversarial game In the game outlined in the question, the vertex selection decision is taken by Player A and only the coloring decision is taken by Player B. Vertex selection happens in steps 8.a and 8.d.

Although it looks like Player B has free will and choice, they cannot win because the color selection for a vertex has to be done using non-conflicting colors, if such a selection is possible. With 5 colors, there will always be a non-conflicting color available to choose, regardless of which non-conflicting sequence of colors have been chosen prior.

As long as such non-conflicting selections are made every step of the way, the game terminates with all vertices colored (i.e., Player A wins).

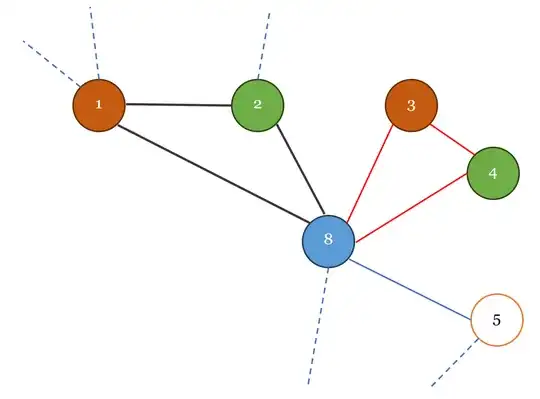

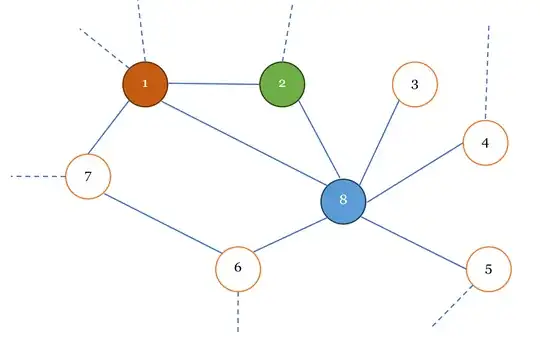

Non-conflicting selections can always be made by coloring triangles with $v$ as one of the vertices (the apex) of the triangle and choosing two non-conflicting colors for the other two vertices. The coloring decisions of two triangles apexed on the same vertex can be done without an additional color use if the two triangles don't share a side. In the example below vertex $8$ is the apex.

It can also be done if the triangles share a side; just use the color of the vertex opposite the shared side. In the example below, the edge $2-8$ is the shared side.

Once all triangles are colored, we will be left with single edges from $v$ to an uncolored neighbor. Any color other than the color of $v$ is non-conflicting for that neighbor.

If there are no triangles with $v$ as an apex, then a single color different from the color of $v$ is optimal. But even if Player A chooses different colors to suboptimize and sabotage the game, the next coloring for vertex $u$ can be done using the color of $v$ since $v$ is not connected to that uncolored vertex $u$.

Existence of valid coloring of node adjacent to partially colored graph. Suppose $G$ has been partially colored after $v$ has been colored and removed. We want to color vertex $u$ adjacent to a colored vertex $w$ ($w \ne v$ because it has been removed from consideration). We can reuse the color assigned to $v$ as it would be non-conflicting as long as $u-v-w$ is not a triangle. We have already shown that triangles always have a valid coloring. Therefore, a non-conflicting selection can always be made for a node adjacent to a partially colored subgraph.

Illustration

The following illustration shows the step by step coloring of a sample graph.

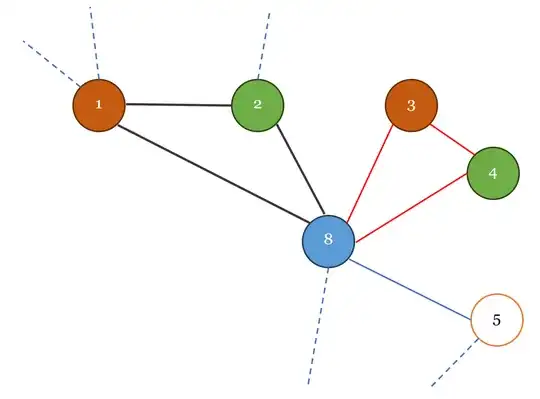

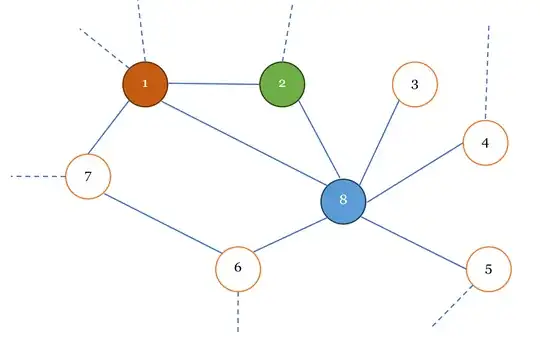

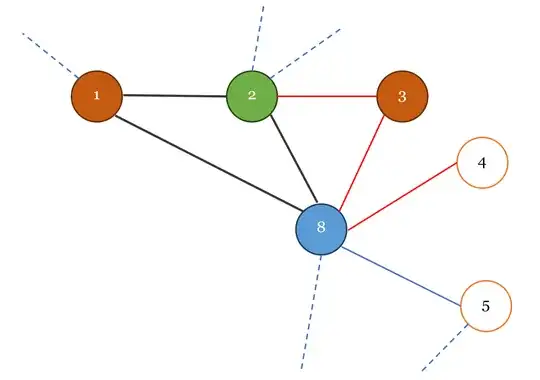

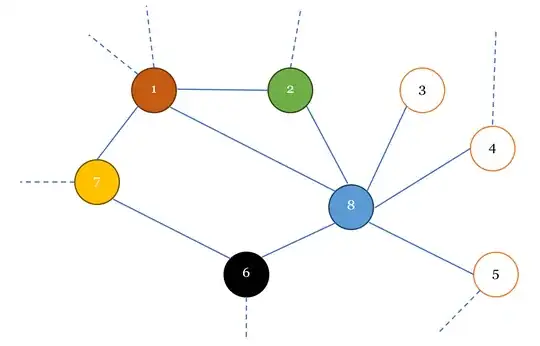

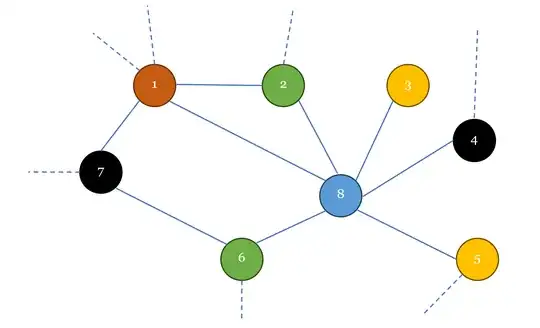

The subgraph of $G$ containing vertices $1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8$ in which let us say vertex $8$ with degree $6$ is the maximal degree vertex. The connected neighbor subgraph of $v_8$ is $1-2-3-4-5-6-(8)$. Player B picks a color, say $blue$.

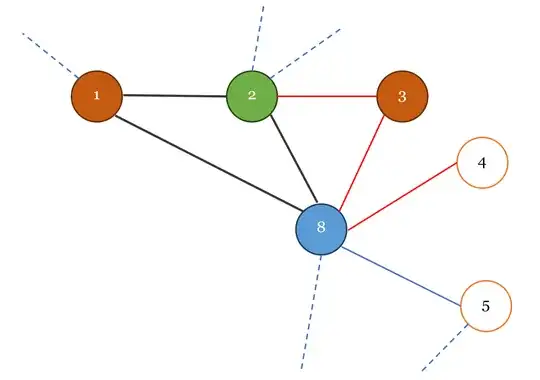

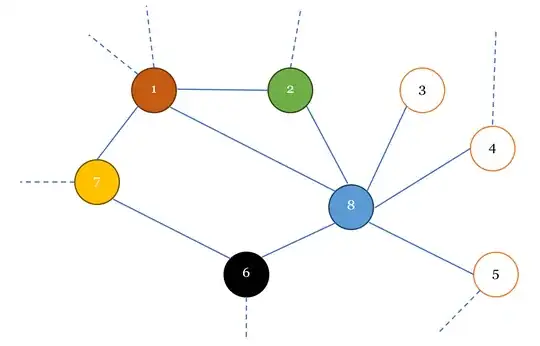

Player A then gives picks the neighbor with highest $ColoredDegree(8)$ which is $1$. Once Player B colors $1$, the next neighbor picked will be $2$. This sequence of $Pick(v)$ ensures that triangles are colored first. Suppose Player B wants to sabotage the game and adversarially chooses different colors for each node, say $1 \leftarrow red, 2 \leftarrow green$.

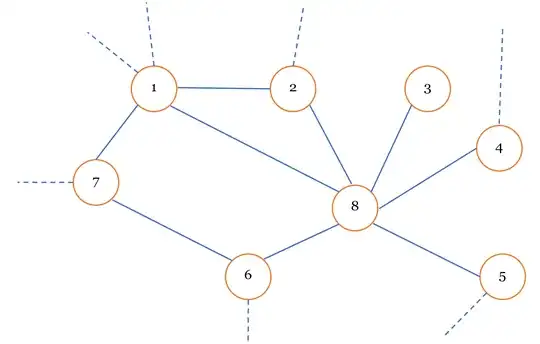

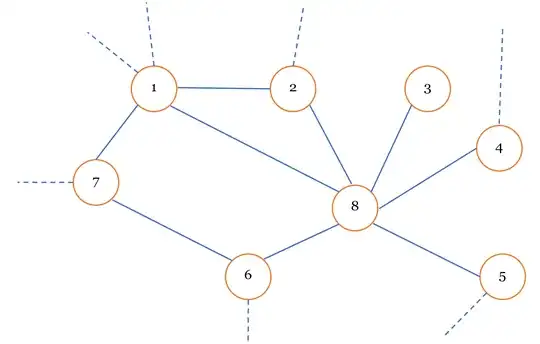

Player A then gives the vertices $7-6$.

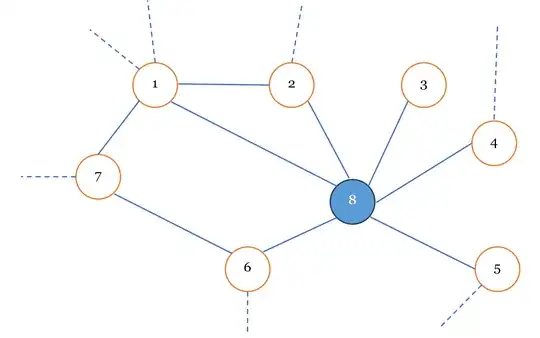

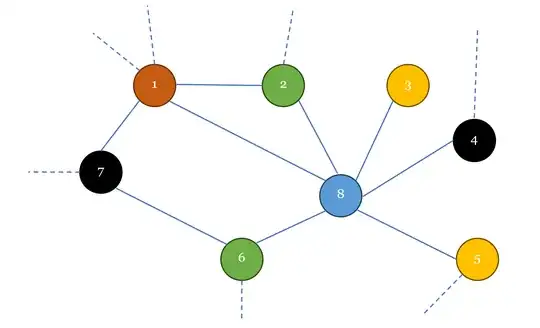

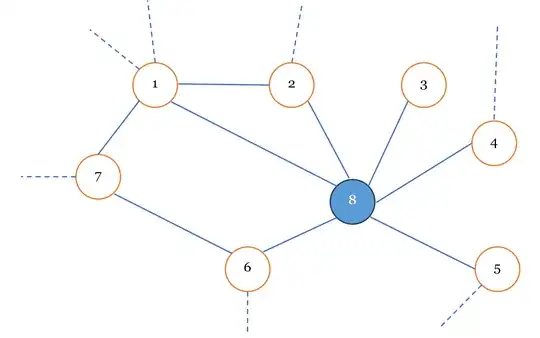

The next sequence of vertices for coloring is $4-5-3$ or $5-4-3$. Suppose Player A picks $5$. The choice of non-conflicting colors for $5$ are $\{red, green, yellow, black\}$. Any choice would do. There are three uncolored vertices and $4$ non-conflicting color choices. A valid coloring is possible regardless of which colors Player B chooses (as long as they are non-conflicting in every color assignment).

References:

All 2-D maps are planar graphs. See accepted answer for Proof that every map produces a planar graph - Four Colour Theorem

Five Color Theorem. We can color any planar graph with 5 colors. See: http://www-math.mit.edu/~djk/18.310/18.310F04/planarity_coloring.html