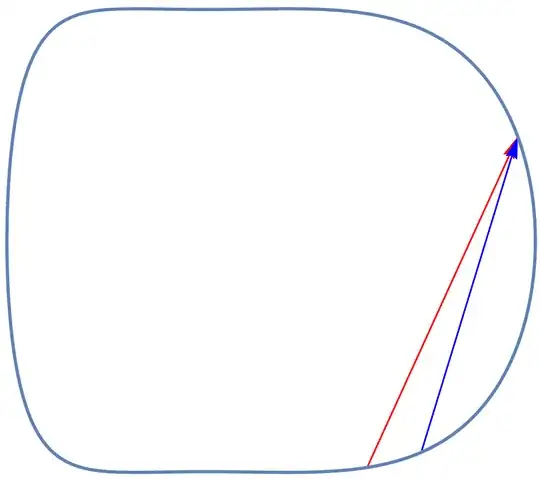

Consider a plane billiard table $D \subset \mathbb{R}^2$ (i.e. a bounded open connected set) with smooth boundary $\gamma$ being a closed curve. Next, let $M$ denote the space of tangent unit vectors $(x,v)$ with $x$ on $\gamma$ and $v$ being a unit vector pointing inwards. We then define the billiard map $$ T : M \to M. $$ To understand the map $T$, we consider a point mass traveling from $x$ in direction $v$. Let $x_1$ be the first point on $\gamma$ that this point mass intersects and suppose that $v_1$ is the new direction of the mass upon incidence. Then $T$ maps $(x,v)$ to $(x_1, v_1)$.

We now introduce an alternate ''coordinate system'' describing $M$. Parametrize $\gamma$ by arc-length $t$ and fix a point $(x,v) \in M$. We can find $t$ such that $x = \gamma(t)$ and let $\alpha \in (0, \pi)$ be the angle between the tangent line at $x$ and $v$. The tuple $(t, \alpha)$ uniquely determines the point $(x,v)$ in $M$, and thus offers and alternative description of this space.

My question is as follows: I want to show that the area form given by $$ \omega := \sin{\alpha}\,\mathrm{d}\alpha \wedge \mathrm{d}t $$ is invariant under $T$.

I found a proof of this invariance property proof in S. Tabachnikov's Geometry and billiards but I'm having some trouble understanding a critical part of the proof.

If anyone can explain the proof to me (or provide me with another proof) I would highly appreciate it. An intuitive explanation is also appreciated, but I am looking for a rigorous proof if possible. We restate this theorem formally below and provide the proof as given by Tabachnikov.

Theorem 3.1. The area form $ω = \sin α \,dα \wedge dt$ is $T$-invariant.

Proof. Define $f(t, t_1)$ to be the distance between $\gamma(t)$ and $\gamma(t_1)$. The partial derivative $\frac{\partial f}{\partial{t_1}}$ is the projection of the gradient of the distance $\left\vert{\gamma(t)\gamma(t_1)}\right\vert$ on the curve at point $\gamma(t_1)$. This gradient is the unit vector from $\gamma(t)$ to $\gamma(t_1)$ and it makes angle $\alpha_1$ with the curve; hence $\partial f/\partial t_1 = \cos{\alpha_1}$. Likewise, $\partial f/\partial t = -\cos{\alpha}$. Therefore, $$ \mathrm{d}f = \frac{\partial f}{\partial t} \mathrm{d}t + \frac{\partial f}{\partial t_1}\mathrm{d}t_1 = -\cos{\alpha}\,\mathrm{d}t + \cos{\alpha_1}\,\mathrm{d}t_1 $$ and hence $$ 0 = \mathrm{d}^2f = \sin{\alpha}\mathrm{d}\alpha \wedge \mathrm{d}t - \sin{\alpha_1} \mathrm{d}\alpha_1 \wedge \mathrm{d}t_1. $$ This means that $\omega$ is a $T$-invariant form.

The above proof is copied directly from the book. I have the following questions about his method:

- Is the domain of $f$ the set $M\times M$?

- In the proof, are we specifically considering $(t, \alpha)$ and $(t_1, \alpha_1)$ such that $T (t, \alpha) =(t_1,\alpha_1)$?

- I am having a hard time understanding how the author obtains $\partial f/\partial t_1 = \cos{\alpha_1}$ and $\partial f/\partial t = -\cos{\alpha}$. The explanation given feels mostly heuristic, how could I go about constructing a rigorous proof?