when trying to prove the derivative i ended up with

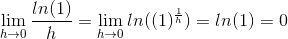

$$\lim_{h \to 0}\frac{\ln(x+h)-\ln(x)}{h}=\lim_{h \to 0}\frac{\ln(\frac{x+h}{h})}{h}=\lim_{h \to 0}\ln((1+\frac{h}{x})^{(\frac{1}{h})}$$ and $$\frac{h}{x}\approx0$$ so

as you can see i attempted to solve it by treating $\frac{h}{x}$ as if its zero due to it being arbitrarily small but i got the wrong answer. now when trying to prove the derivative of $x^2$ i ended up with something similar:

$$\lim_{h \to 0}\frac{(x+h)^2-x^2}{h}=\lim_{h \to 0}\frac{x^2+h^2+2xh-x^2}{h}=\lim_{h \to 0}\frac{h^2+2xh}{h}=\lim_{h \to 0}h+2x=2x$$

here i treated h as if it were zero due to it being arbitrarily small and i got the right answer. was i wrong for treating $\frac{h}{x}$ as if its zero? (please forgive me for not writing the equations formally i am fairly new at this edit: when i was solving