From the 1951 novel The Universe Between by Alan E. Nourse.

Bob Benedict is one of the few scientists able to make contact with the invisible, dangerous world of The Thresholders and return—sane! For years he has tried to transport—and receive—matter by transmitting it through the mysterious, parallel Threshold.

[...]

Incredibly, something changed. A pause, a sag, as though some terrible pressure had suddenly been released. Their fear was still there, biting into him, but there was something else. He was aware of his body around him in its curious configuration of orderly disorder, its fragments whirling about him like sections of a crazy quilt. Two concentric circles of different radii intersecting each other at three different points. Twisting cubic masses interlacing themselves into the jumbled incredibility of a geometric nightmare.

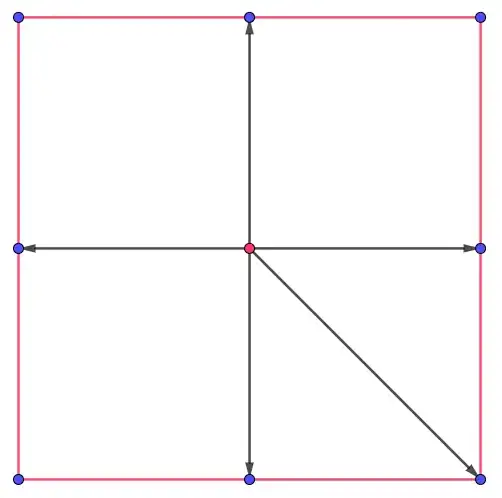

The author might be just throwing some terms together to give the reader a sense of awe, but maybe there's some non-euclidean geometry where this is possible.