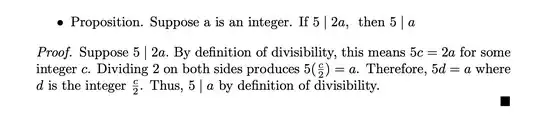

I am studying some Discrete Mathematics and reached the section on simple direct proofs. I was asked to prove that if $5\mid2a$, then $5\mid{a}$. Can someone please tell me if this proof is viable or nor

- 369

-

8Why does $2|c$? – Shubham Johri Aug 08 '19 at 15:37

-

1There is an important component in the proof that cannot be omitted, and that is that $5$ and $2$ are relative prime. Replace $5$ by $6$ and you see the statement does not work. – imranfat Aug 08 '19 at 15:40

-

1Mohammad.Look up Euclid's lemma. – Peter Szilas Aug 08 '19 at 15:53

-

4No. It isn't valid. Why is $\frac c2$ and integer? Why isn't $\frac 52$ an integer. Perhaps somehow $2|5c$ but $2$ doesn't divide either $5$ or $c$? – fleablood Aug 08 '19 at 16:20

-

1Unnecessarily oblique proof: Let $2c = 5d$ then $5(c-2d) =5c-10d = 5c-2*5d=5c-4c =c$. – fleablood Aug 08 '19 at 17:04

6 Answers

No, it is not correct. When you write about “the integer $\frac c2$”, you are assuming that $\frac c2$ is an integer. How do you know that?

You can use Euclid's lemma: since $5$ is prime and $5\mid2a$, then $5\mid2$ or $5\mid a$. But you know that $5\nmid2$. Therefore, $5\mid a$.

- 440,053

-

If I proved that $\frac{c}{2}$ is an integer, would that make my proof valid? – sirferrum Aug 08 '19 at 19:05

-

2Yes, but proving that is exactly as easy as proving that $\frac a5$ is an integer, which is what you want to prove. – José Carlos Santos Aug 08 '19 at 19:07

-

@sirferrum ^^^ i.e. $,5c = 2a\iff \dfrac{c}2 = \dfrac{a}5\ $ so $\ 2\mid c\iff 5\mid a\ \ $ – Bill Dubuque Aug 04 '24 at 05:24

You need to include a proof that $c/2$ is an integer. But you can do this from

$$5c=2a\implies c=2a-4c\implies c/2=a-2c$$

If you like, you can rewrite the entire proof as

$$2a=5c\implies a=5(a-2c)$$

- 81,321

-

I'm sorry if this might be a dumb question, but how did $\frac{c}{2}=a-2c$ prove that $\frac{c}{2}$ is an integer? – sirferrum Aug 08 '19 at 19:04

-

1

-

1@MohamedTlili It's not a dumb question since the above approach obfuscates the essence of the matter. It is much clearer to use a parity argument - see my answer. – Bill Dubuque Aug 08 '19 at 20:10

-

@sirferrum Such proofs are essentially instances of a Bezout-based proof of Euclid's Lemma, i.e. $5\mid 5a,2a,\Rightarrow, 5\mid 5a -2,(!!\overbrace{2a}^{\large c}!!) = a,,$ i.e. $,5\mid 5a,2a\Rightarrow 5\mid \gcd(5a,2a)=\gcd(5,2)a=a\ \ $ – Bill Dubuque Aug 04 '24 at 05:36

No. It isn't valid. Why is $\frac c2$ and integer? Why isn't $\frac 52$ an integer. Perhaps somehow $2|5c$ but $2$ doesn't divide either $5$ or $c$?

You will need Euclid's Lemma or something equivalent to it.

Euclid's Lemma states: If $p$ is a prime and $p|ab$ then $p|a$ or $p|b$ (or both).

If you know Euclid's Lemma this is facile. $5$ is prime so $5|2a$ so either $5|2$ or $5|a$. And $5\not \mid 2$.

I'm assuming either this is an exercise in recognizing the applications of Euclid's Lemma, or that Euclid's Lemma has not been proven yet.

The standard way to prove Euclid's Lemma is with Bezout's theorem (which in turn is proved by Euclid's Algorithm) but for curiosity sake it might be interesting to be prove it directly.

$5-2*2 = 1$

$5c - 2*2c = c$

Now we know $5|2c$ so there is an integer, $d$, so that $2c = 5d$ so

$5c - 2*5d = c$ and

$5(c-2d) = c$.

..... Don't know about you but I think that's kind of neat.

- 130,341

-

Euclid is overkill when a simple partiy argument suffices - see my answer. – Bill Dubuque Aug 08 '19 at 20:14

-

Okay, but although parity is intuitive is it actually proven at a level this basic? I mean if $ab$ is even why does it follow that either $a$ or $b$ is even? Aren't we going to great lengths to avoid realizing we need to prove Euclids lemma eventually. – fleablood Aug 08 '19 at 21:04

-

Usually parity arithmetic is introduced very early in coursed on elementary number theory and discrete math (as motivation for many things that follow). – Bill Dubuque Aug 08 '19 at 21:07

-

Yeah, but is that justified? I've never seen a number theory explain why parity arguments are justified without some form of circular reasoning. You can't claim $ab=even$ means either $a$ or $b$ is even without either Euclid's Lemma or the remainder theorem. And you can't prove the remainder theorem without the Archemedian property which I've seldom seen in the first days of a number theory class. – fleablood Aug 08 '19 at 21:19

-

It' need not be circular since e.g. parity arithmetic laws can be proved directly by induction, e.g. here to prove that if $,2\nmid a,$ then $,2\mid an,\Rightarrow, 2\mid n,$ we can use $,2\mid an!\iff! 2\mid a(n!-!2),$ in the inductive step. $\ \ $ – Bill Dubuque Aug 04 '24 at 05:16

-

Well, I wrote this 5 years ago... but I did say "something equivalent". I think the 5 year ago me would say the result of a parity argument is equivalent to a specific incident of Euclid's lemma. I mean why are we doing these excercises. If the goal is to move along aren't we working toward Euclid's lemma anyway. Still you are right (says five year older me) that we need only what works. – fleablood Aug 04 '24 at 15:45

Here's a valid proof:

First, we'll prove if $a|bc$ and $gcd(a,b)=1$, then $a|c$.

If $gcd(a,b)=1$, that means there are integers $x$ and $y$ so that $ax+by=1$.Multiplying both sides by $c$ yields $acx+bcy=c$. Note that $a|acx$ and $a|bcy$ so $a|c$. Plug in $a=5,b=2$ and there you have it.

To deduce $\,5(\color{#c00}{c/2}) = a\,\Rightarrow\,5\mid a\,$ we need $\,\color{#c00}{c/2}\,$ an integer; it's true by $\,5c=2a$ is even so $c$ is even. This must be explicitly mentioned for the proof to be rigorous. As others noted we could instead use Euclid's Lemma, but that's a bit overkill when a simple parity argument suffices.

Remark other proofs are essentially instances of a Bezout-based proof of Euclid's Lemma, i.e. $5\mid 5a,2a\,\Rightarrow\, 5\mid 5a -2(2a) = a,\,$ i.e. $\,5\mid 5a,2a\Rightarrow 5\mid \gcd(5a,2a)=\gcd(5,2)a=a\ \ $

- 282,220

-

1But isn't a "simple parity" argument just a specialized case of Euclid's lemma when $p = 2$? Otherwise how do you know if $ab$ is even that one of $a$ or $b$ must be even. – fleablood Aug 08 '19 at 21:19

-

@fleablood The point is that one can (and often does) introduce parity arithmetic long before deeper properties like Euclid's Lemma. Parity arithmetic only requires knowing how to divide by $2$ (with remainder). – Bill Dubuque Aug 08 '19 at 21:40

-

@BillDubuque I wholeheartedly agree, I already learned parity and it's easy to use but I haven't been introduced to Euclid's Lemma yet. – sirferrum Aug 09 '19 at 13:00

-

Then shouldn't we say "$5c=2a$ is even.... and as $5$ is odd and the product of two odds would be odd we must have ... $c$ is even". It seems to me that "$5c=2a$ therefore $c$ is even" requires we note the reason for that. Just as it is essential that we note that $c$ must be even, I think we also need to note that $5$ is odd. (Then we can say $5c$ is even if and only if $c$ is even). [Obviously $5$ is odd but I think to a student, the leap $5c=even\implies 5=even$ might not be clear without so noting.] – fleablood Aug 04 '24 at 16:19

The fundamental theorem of arithmetic states that every integer greater than $1$ is a product of prime numbers. This factorization is unique up to the order of primes.

From $5\vert 2a$ you get $2a=5m$ for some integer $m$. Since $2$ and $5$ are coprime, the representation of $a$ must contain the factor $5$, thus $a$ is divisible by $5$.

- 2,748

-

The fundamental theorem of arithmetic doesn't state that every integer is a product of prime numbers. It is only for integers greater than 1. – Aug 08 '19 at 16:07

-

-

The problem isn't in your proof for OP's problem. It's merely your definition of the fundamental theorem of arithmetic:) – Aug 08 '19 at 16:10

-

The fundamental theorem of arithmetic is applied in the sentence 'the representation of $a$ must contain the factor $5$. – Fakemistake Aug 08 '19 at 16:13

-

-

-

It is monstrous overkill to use the Fund. Thm. of Arithmetic (vs. parity) here. $\ \ $ – Bill Dubuque Aug 04 '24 at 05:20

-

@BillDubuque I know, I just wanted to show an alternative. Here I go with Jose Carlos Santos‘ answer, but yours is also nice – Fakemistake Aug 05 '24 at 16:57