Could you please explain, how one gets this Parametric representation of a solid trapezoid ? I mean the procedure and not the answer. I have some linear geometry (as polygons), and I need to represent them in the parametric form. I have no idea how to get the parametric form of the rectangle or triangle and how to build the complex geometries (like trapezoid). May be some hints or where can I find it in the literature? Here are the examples of my geometries.

-

Welcome to stackexchange. In order for us to help you we need much more context. Please [edit] the question to show us a few particular polygons you care about, and why, so we can see how you are representing them. You seem to want a map from the unit square to your polygon. There is probably no easy way to do that in general.. Are you looking for an algorithm? – Ethan Bolker May 08 '19 at 15:09

-

1Possibly helpful: https://math.stackexchange.com/questions/315828/transformation-between-square-and-a-polygon – Ethan Bolker May 08 '19 at 15:14

-

I have taken the liberty to modify your title in order to attract more attention for future readers. Furthermore, I have added tag "polygons". – Jean Marie May 09 '19 at 06:34

-

It is unclear if you want to parameterize the outlines or the whole area. Maybe better to tell us why you need that. Sounds like an XY question. – May 10 '19 at 09:54

-

I need to parametrize the outlines, as I need to find the coordinates of the surface points. So the coordinates of the outlines in a parametric form – Ekaterina Deriabina May 10 '19 at 09:57

1 Answers

Here are two different parametrization methods for a convex quadrilateral $ABCD$, trapezoid and triangles being particular cases.

First method : The so-called "bilinear interpolation", using a barycentric approach:

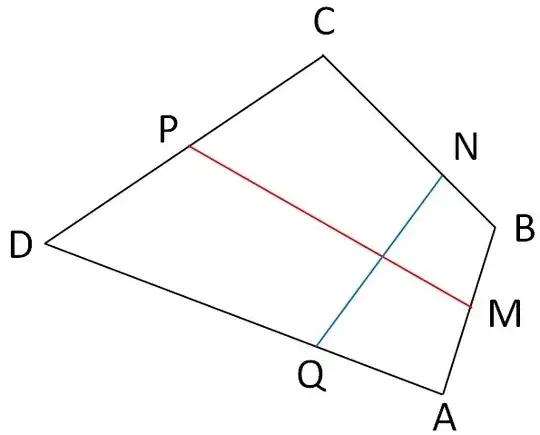

a) Use a parametric description of the two opposite sides $AB$ and $DC$:

$$\begin{cases}M&:=&(1-u)A+uB \in [AB]\\ P&:=&(1-u)D+uC \in [DC]\end{cases}$$

using a common parameter $0 \leq u \leq 1.$

b) Do the same on the two other opposite sides $BC$ and $AD$, using a second parameter $0 \leq v \leq 1$:

$$\begin{cases}N&:=&(1-v)B+vC \in [BC]\\ Q&:=&(1-v)A+vD \in [AD]\end{cases}$$

The point of intersection of line segments $[MP]$ and $[NQ]$ is defined in a unique way by the pair $(u,v)$ playing the role of coordinates ; in a reciprocal manner, every point interior to the quadrilateral has such a representation.

Fig. 1 : Case $u=1/2, v=1/3$ ($M$ and $P$ are the midpoints of their line segments).

Grouping operations a) and b) above, the intersection point can be written :

$$I=u'v'A+uv'B+u'vD+uvC\tag{*}$$

(with $u'=1-u, \ v'=1-v$). Indeed (*) can be written as a two-steps barycentration process:

$$I = \color{red}{v'}(\color{blue}{u'}A+\color{blue}{u}B)+ \color{red}{v}(\color{blue}{u'}D+\color{blue}{u}C)$$

But we can also switch the order of barycentrations with the following gatherings :

$$I = \color{red}{u'}(\color{blue}{v'}A+\color{blue}{v}D)+ \color{red}{u}(\color{blue}{v'}B+\color{blue}{v}C)$$

Formula (*) can be written in the form :

$$\begin{cases}x& = &a+bu+cv+duv \\ y &= &e+fu+gv+huv\end{cases}\tag{1}$$

for certain fixed coefficients $a,b,...h$.

References :

The long answer by NominalAnimal to this SE question : Quadrilateral Interpolation

A previous answer of mine https://math.stackexchange.com/q/1792460 showing that the method can be extended to a non planar case.

What is the inverse of this transformation from a rectangle to a quadrilateral?

for a classical application to color interpolation : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bilinear_interpolation

Remark : this transformation is not amenable to a projective transform (see below) because for example lines $AB$, $CD$ and $NQ$ do not intersect into a single point.

Second method : Projective transformation:

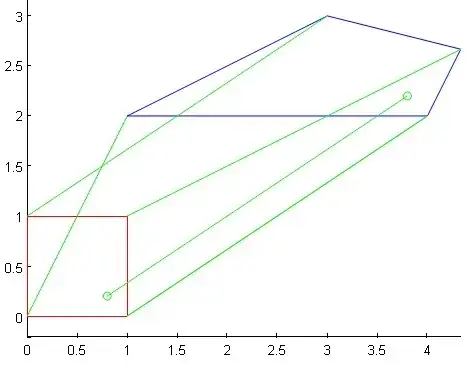

Convex quadrilateral $ABCD$ could as well be considered as the image by a projective transformation of square $[0,1] \times [0,1]$ with natural coordinates $(u,v)$ mapping (by a so-called homography) the square onto the quadrilateral. We just need for that to find the matrix entries of the corresponding homography.

If for example, we want to "map" the reference square with current point $(u,v) \in [0,1] \times [0,1]$, to the quadrilateral given on the figure below, we will use the projective transformation :

$$x=\dfrac{au+bv+c}{gu+hv+1}, \ \ \ y=\dfrac{du+ev+f}{gu+hv+1}\tag{2}$$

with fixed coeffients that we store in a so-called homography matrix :

$$H=\begin{pmatrix}a&b&c\\d&e&f\\g&h&1\end{pmatrix}=\begin{pmatrix}7&5&1\\2&4&2\\1&1&1\end{pmatrix}$$

(please note that the entries of the common denominator are placed in the third row of this matrix).

Sanity check : the image of vertex $(0,0)$ on the square is vertex $(1,2)$ on the quadrilateral.

The entries of matrix $H$ are obtained through 8 equations expressing that the image of $(0,0)$ is $(x_A,y_A)$ (known quantities), the image of $(0,1)$ is $(x_B,y_B)$, etc.

Being able to go the other way (being able to retrieve $(u,v)$ if (x,y) is known), is essential. We need for that inverse formulas that are readily obtained : they belong to the same family of projective transformations using the entries of $H^{-1}$.

Fig. 2 : The square and its image (a quadrilateral) by an homography. The five green line segments connect a point $(u,v)$ and its image $(x,y)$.

Appendix : Matlab program that has generated Fig. 2 :

i=complex(0,1); R=[7,5,1,2,4,2]; a=R(1);b=R(2);c=R(3);d=R(4);e=R(5);f=R(6); Z=@(x,y)((a*x+b*y+c)./(x+y+1)+i*(d*x+e*y+f)./(x+y+1)); plot(Z([1,1,0,0,1],[0,1,1,0,0]),'b');axis equal plot([1,1,0,0,1],[0,1,1,0,0],'r') plot([1+0i,Z(1,0)],'g')

- 88,997