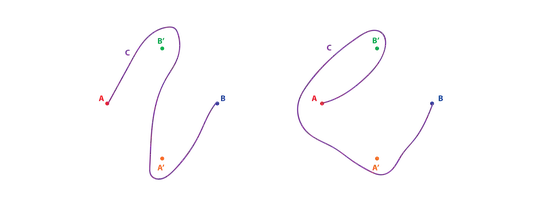

Edit $\quad$ This answer misses the situations where a curve does not fall under the two cases mentioned (see the following image for two examples). It is also possible that $Y$ from the first case is empty (for instance, when $D=C$). However, this does not affect the outcome. One last point; I realize that the third assumption is not so easily justified (take as an example a curve that intersects itself infinitely many times). We, therefore, need a specific definition of a curve that does not allow infinite self-intersections to avoid complications.

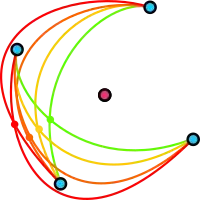

Here is an idea:

We can make the following assumptions:

A.1 $\quad$ As YiFan says, we can assume without loss of generality that the points are $A=(-1,0)$, $B=(1,0)$, $A'=(0,-1)$, and $B'=(0,1)$.

A.2 $\quad$ The curve $C$ connecting $A$ to $B$ does not pass through $A'$ or $B'$. (The statement is trivially true in such cases.)

A.3 $\quad$ The curve $C$ does not intersect itself. (Given such a curve, we can simply take another curve that is a subset of it with no self-intersections.)

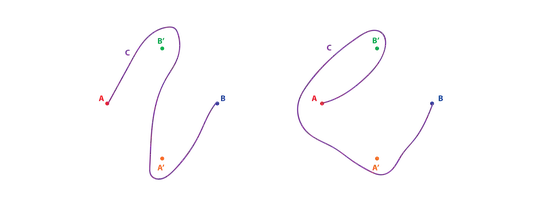

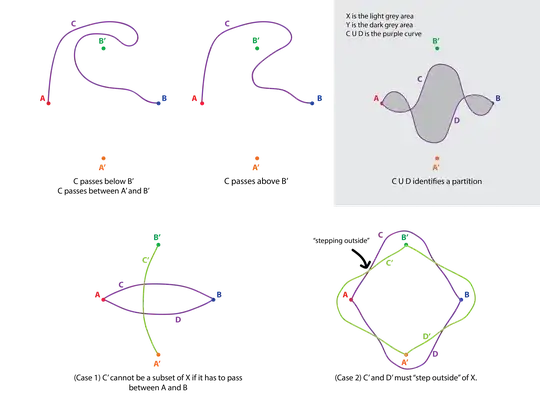

We then have two cases:

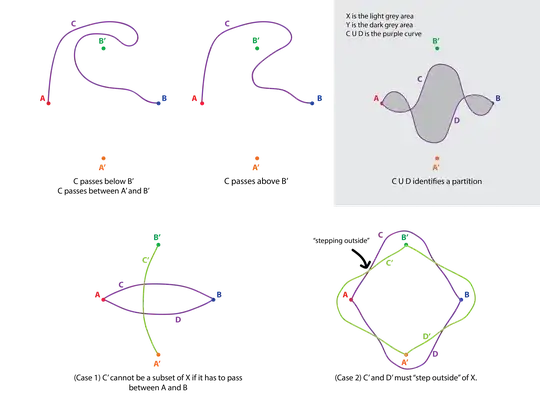

Case 1 $\quad$ The curve $C$ passes "below" $B'$ and "above" $A'$. Let $D$ be $C$ rotated about the origin $180$ degrees. Clearly $C\cup D$ identifies a partition of the plane; The "perimeter" $P$ of $C\cup D$, the unbounded subset $X$ consisting of points "outside of" $P$, and the bounded subset $Y$ (possibly empty; see above) consisting of points "inside of" $P$. If the curve $C'$ is a subset of $X$, then it will not be "going between" $A$ and $B$ as it is supposed to, therefore it has a point shared with $P$, and we are done.

Case 2 $\quad$ The curve $C$ passes "above" $B'$ or "below" $A'$. We consider only the former, and the latter is similar. Again, we let $D$ be the rotation of $C$ by $180$ degrees, and we have $P$, $X$, and $Y$ as in case 1. In this case we know that $A'$ and $B'$ are in $Y$. If the curve $C'$ along with its $180$ degree rotation $D'$ want to identify, using their perimeter, a bounded subset of the plane that contains $A$ and $B$ (as they are supposed to), then they must "step outside" of $X$. And when they do so, they intersect $P$, and we are done again.

Below are five figures that help illustrate the idea:

The above can be formalized using concepts of elementary topology, and the not-so-elementary theorem known as Jordan Curve Theorem. I will try to post a formal answer once I know what to do with the cases I am missing.

For now, I will give a few formulations that can motivate a formalization.

By Jordan Curve Theorem, every closed curve ($C \cup D$ in our application) divides the plane into at least two path-connected components, one of which is the unbounded exterior which I call $X$. The union of the other bounded components is what I call $Y$, and the perimeter $P$ is the closure of $Y$ without $Y$'s interior.

As to what I mean by "below" or "above": Given a curve $C$, we walk on it from $A$ to $B$, and we take note how we travel by writing a sting $\rho$ of Greek letters. If we pass through the region of the $Y$-axis below $A'$, we write $\alpha$ for going left-to-right and $\alpha^{-1}$ for going right-to-left. Similarly, we use $\beta$ and $\gamma$ for the region between $A'$ and $B'$ and the region above $B'$, respectively. We use $\delta$ (or $\epsilon$, respectively) when we make a clockwise rotation around $A$ (or $B$), and $\delta^{-1}$ (or $\epsilon^{-1}$) for a counterclockwise turn.

Then we verify that Case 1 deals with those curves whose reduced $\rho = \sigma \beta \tau$, where $\sigma$ (or $\tau$, respectively) only refers to rotations about $A$ (or $B$). While Case 2 deals with those where $\rho = \sigma \alpha \tau$ or $\sigma \delta \tau$, where $\sigma$ and $\tau$ are as before. Furthermore, the situations which I miss are those whose $\rho$ does not have such a form.