A colleague of mine was curious about the number of possible start-configurations in a game. The game itself is not known to me, but the question which he formulated as urn problem was interesting.

Urn problem:

Assume we have an urn containing 100 balls. The balls are colored, 25 are red, 25 blue, 25 green and 25 are black. We pick four balls without replacement and repeat this step until the urn is empty.

We so obtain 25 groups of four balls each and the question is: how many configurations of this type are possible? Thereby we may assume the order of the $4$ balls in each group is not relevant as well as the order of the $25$ groups is not relevant.

A reformulation:

Given an alphabet $V=\{1,2,3,4\}$ we consider $4$-letter words $x_1x_2x_3x_4$ with $1\leq x_1\leq x_2\leq x_3\leq x_4\leq 4$ when considered as numbers.

These $4$-letter words are building blocks of words of length $100$. We take $25$ blocks of this kind to form a $100$-letter word $w=b_1b_2\ldots b_{25}$ with the property that $b_j\leq b_{j+1}, 1\leq j\leq 25$ when considered as numbers.

Question: How many words of this type contain exactly $25$ characters of each of the characters $j\in V, 1\leq j\leq 4$.

In general we are given an alphabet $V=\{1,2,\ldots,q\}$ with size $|V|=q$.

(a) We consider words of length $N$ and building blocks $x_1x_2\ldots x_M$ of size $M$ with $1\leq x_1\leq x_2\leq \cdots \leq x_M\leq q$ and $M|N$, i.e. $N$ being an integer multiple of $N$.

(b) The words are of the form $w=b_1b_2\ldots b_{N/M}$ with $b_j\leq b_{j+1}, 1\leq j \leq N/M-1$.

(c) We are looking for the number $\color{blue}{A_q(N,M)}$, the number of words as specified in (a) and (b) which contain $N/q$ characters of each of the characters $j\in V, 1\leq j\leq q$ implying that $N$ is an integer multiple of $q$ as well.

In this setting the urn problem is asking for $\color{blue}{A_4(100,4)}$.

The number of building blocks of $A_q(N,M)$ can be easily determined. It is \begin{align*} \sum_{1\leq x_1\leq x_2\leq\cdots\leq x_M\leq q}1=\binom{M+q-1}{M}\tag{1} \end{align*}

A generating function of (1) can be easily derived. We have \begin{align*} \sum_{M=0}^\infty\sum_{q=0}^\infty x^My^q\binom{M+q-1}{M}&=\frac{1-x}{1-x-y}\\ &=1+y\left(1+x+x^2+x^3+x^4+\cdots\right)\\ &\qquad+y^2\left(1+2x+3x^2+4x^3+5x^4+\cdots\right)\\ &\qquad+y^3\left(1+3x+6x^2+10x^3+\color{blue}{15}x^4+\cdots\right)\\ &\qquad\cdots \end{align*} Denoting with $[x^M]$ the coefficient of $x^M$ in a series we see for instance $[x^4y^3]\frac{1-x}{1-x-y}=\binom{6}{2}=15$ which is the number of valid building blocks of size $4$ when given a three letter alphabet $V=\{1,2,3\}$. These $15$ building blocks are \begin{align*} 1111\quad1122\quad1222\quad1333\quad2233\\ 1112\quad1123\quad1223\quad2222\quad2333\\ 1113\quad1133\quad1233\quad2223\quad3333\\ \end{align*}

The difficult part (at least for me) is to determine the number of valid words $A_q(N,M)$ which can be generated from these building blocks. I've tried to derive a generating function which describes this scenario, but I wasn't successful up to now.

Posets: Another approach could be using posets based upon the approach:

Start with an empty word and append $N/M$ times a building block respecting the ordering given in (b).

Derive a generating function for the number of valid posets.

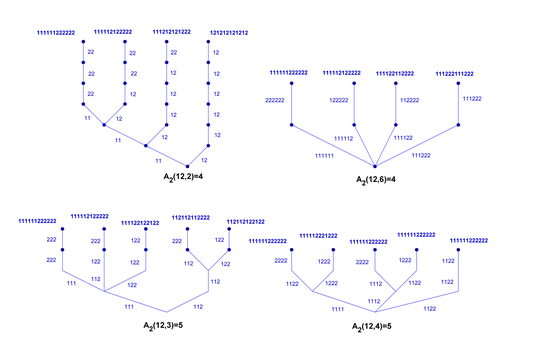

In order to better see the situation, here is a manageable example. We are looking for $A_2(12,M)$ the number of words of length $12$ from a two-letter alphabet with different block-sizes $M$ following (a) - (c) from above. The Hasse-diagrams for $M=2,3,4,6$ are:

We see graded posets of length $N/M$ with $A_2(12,2)=A_2(12,6)=4$ and $A_2(12,3)=A_2(12,4)=5$ indicating the symmetry \begin{align*} A_q(N,M)=A_q(N,N/M) \end{align*}

Here is a list of small values of $A_2(N,M)$: $$ \begin{array}{r|rrrrrr} M&1&2\\ A_2(2,M)&1&1\\ \hline M&1&2&4\\ A_2(4,M)&1&2&1\\ \hline M&1&2&3&6\\ A_2(6,M)&1&2&2&1\\ \hline M&1&2&4&8\\ A_2(8,M)&1&3&3&1\\ \hline M&1&2&5&10\\ A_2(10,M)&1&3&3&1\\ \hline M&1&2&3&4&6&12\\ A_2(12,M)&1&4&5&5&4&1\\ \end{array} $$

Summary: The question is how to find a formula for $A_q(N,M)$ or how to derive a generating function for these numbers. Alternatively is there an appropriate technique to count the number of posets corresponding to $A_q(N,M)$?