A chi-square distribution is constructed from normal random variables $X_{i=1, \dots ,n}$, each with normal distribution and mean $\mu$ and variance $\sigma^2$. Transforming to standard normal and squaring, i.e.:

$$\frac{(X_i - \bar{X})^2}{\operatorname{Var}(X_i)}\sim N(0,1)^2$$

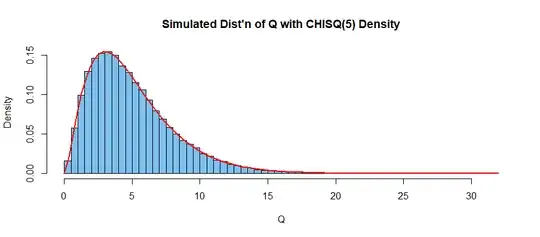

Then add these over all your $n$ random variables, then you get $\chi^2_{n-1}$ - a chi-square with $n-1$ degrees of freedom.

For contingency tables, suppose there are $k$ categories of observations $O_i, i = 1, \ldots , k,$ each with probability $p_i$. The statistic we’re proposing, assuming $O_i \sim \operatorname{Normal}$, is:

$$\frac{(O_i-np_i)^2}{\operatorname{Var}(O_i)} \sim N(0,1)^2$$

The variance of each observation is $np_i(1-p_i)$

For contingency tables, a test to see if the underlying mean is the same across categories, the standard equation taught for calculating the Chi-Square statistic is:

$$\sum_{i=1}^k\frac{(O_i-np_i)^2}{np_i} \sim \chi^2_{n-1}$$

So, where in the equation for assessing contingency tables does the term $(1-p_i)$ disappear to?