Consider the following alternative definition of a parabola:

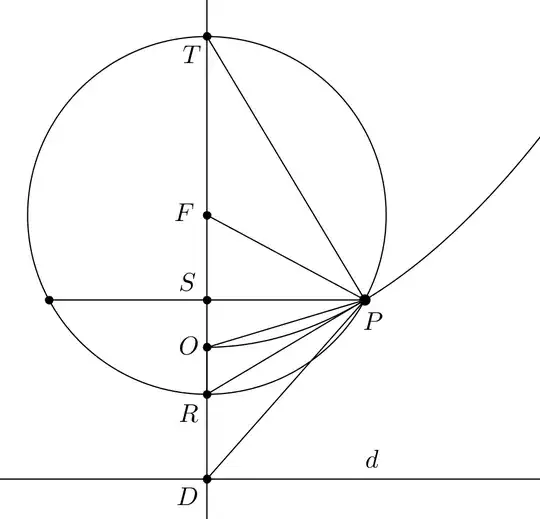

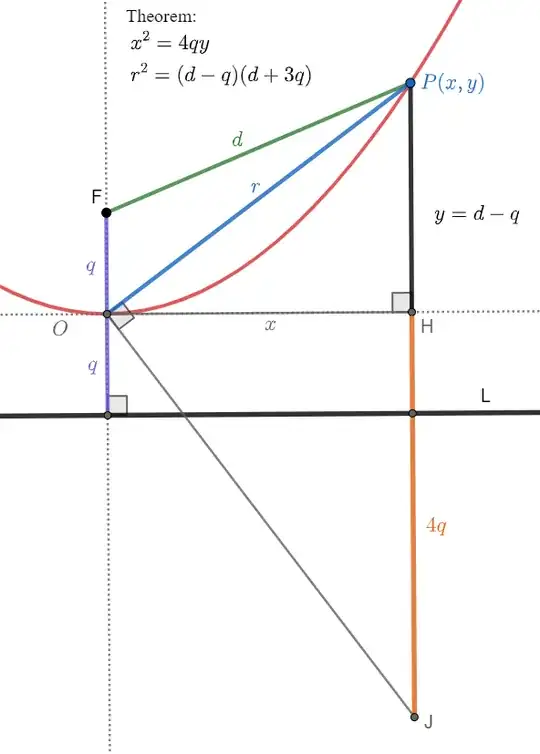

Given two points $F$ and $O$ in the plane, the parabola having focus $F$ and vertex $O$ is the locus of points $P$ of the plane such that $$(FP - OF)(FP + 3 OF) = OP^2.$$

Using coordinates it is easy to see that the definition is equivalent to the usual one. Indeed, if we let $O = (0, 0)$, $F = (0, f)$ for some $f > 0$ and $P = (x, y)$, then the given equation simplifies to $x^2 = 4 f y$, which is precisely the equation of the parabola having focus $F$ and vertex $O$ as it is usually defined.

What I am interested in is a geometric proof that any parabola satisfies the above property, which should hopefully give some insight on why such an equality must hold. I have attempted to prove it in two ways:

- As it is written, the equality seems to say that a certain rectangle (or maybe parallelogram?) has the same area as the square on the line segment $OP$. I have noticed that $FP - OF$ is the distance from $P$ to the tangent line to the parabola at $O$, but I don't know what to do with $FP + 3 OF$.

- The equality can be rewritten as $$OP^2 + (2 OF)^2 = (FP + OF)^2.$$ Now it looks as though it could be proven using the Pythagorean theorem. But I haven't been able to draw a triangle having sides $OP$, $2OF$ and $FP+OF$ so that it can be seen that it is indeed a right triangle.

Any help would be highly appreciated.

(Background: this problem came up while trying to prove a similar property about the cissoid of Diocles, see this other question of mine. The two properties are related through inversion with respect to the unit circle centered at $O$.)