There appears to be little hope of a formal proof, but this is how a standard heuristic argument would treat this problem, so we can determine whether the conjecture is plausible in the vein of Bateman-Horn as mentioned by reuns.

Excluding an asymptotically small number of cases, most of the values $f(p_n,p_{n+1},p_{n+2})$ will be of size roughly $\Theta(m^2 \log^2 m)$, so if they were randomly distributed, we would expect about one in $\log(m^2\log^2 m) \sim 2 \log m$ of them to be prime, which would be $\sim m/(2 \log m)$.

But we're seeing significantly more than that. That's because those numbers are not randomly distributed: for starters, they're all odd, and that accounts for the missing factor of $2$. A random number has a $\frac12$ chance of not being divisible by $2$, but these numbers have double the chance.

However, we're not done yet. They also are unevenly distributed modulo $3$: each of $p_n,p_{n+1},p_{n+2}$ can be viewed as a uniform random sample from the non-zero residues mod $3$. Of these $8$ possible inputs to $xy+yz+zx$, $2$ of them provide $0$. So there is a $\frac34$ chance of these numbers being indivisible by $3$, versus a $\frac23$ chance for a random number: which is a factor of $\frac98$ better. Not as strong as the previous factor of $2$, but not insignificant.

It turns out we can exactly calculate this factor for any given prime modulus $p$: the number of solutions to $xy+yz+zx \equiv 0 \pmod p$ with $x,y,z$ all non-zero is easy to compute, since it's equivalent to $z(x+y) \equiv -xy$. A straightforward calculation gives $(p-1)(p-2)$ zero-producing combinations out of $(p-1)^3$, for a $\frac{p-2}{(p-1)^2}$ chance of being divisible by $p$, which is an advantage of $\frac{p(p^2-3p+3)}{(p-1)^3}$.

For large $p$ this fraction is approximately $1 + \frac{1}{p^2}$, so we can combine all of these multiplicative factors for all primes $p$ into a convergent product yielding a single constant: this is the so-called singular series.

The standard heuristic underlying Bateman-Horn and similar conjectures would then predict that the number of prime values should be asymptotic to:

$$\frac{m}{2\log m}\prod_{p\text{ prime}} \frac{p(p^2-3p+3)}{(p-1)^3} \approx 1.15048 \frac{m}{\log m}.$$

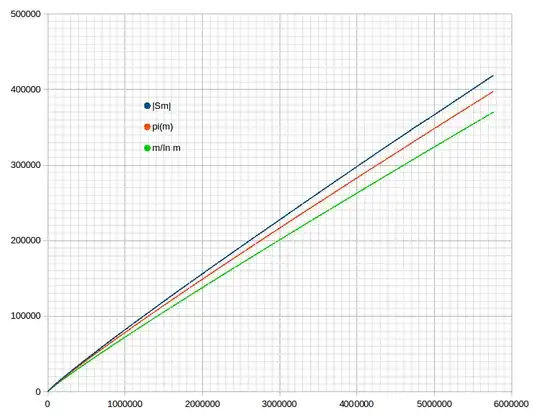

This actually agrees remarkably well with your data, which shows the ratios of $|S_m|$ to $m/\log m$ are:

$$1.1521, 1.1976, 1.1813, 1.1900, 1.1630, 1.1344, 1.1313.$$

However, I don't have a good explanation for why it matches so well, since I would have expected a $O(1/\log m)$ relative error so for these small values of $m$ it should be agreeing to only one digit, not two. There may be something that miraculously cancels out the first-order error and leaves a $O(1/\log^2 m)$ relative error.

Update: For the similar sequence $T_m$, we can do a similar analysis with the polynomial $3(2n+1)^2-4$. The singular series constant (with the factor of $\frac12$ due to the quadratic growth rate) works out

$$\frac12 \cdot 2 \cdot \frac32 \cdot \prod_{p\ge 5\text{ prime}}\big(1-\frac1p\big)^{-1}\big(1-\frac{(3/p)}{p}\big) \approx 2.07508,$$ where $(3/p)$ is the Legendre symbol (so $+1$ if $p \equiv 1,11$ mod $12$ and $-1$ if $p \equiv 5,7$ mod $12$).

This is significantly higher than the constant for $S_m$: much of the reason for this is that $3(2n+1)^2-4$ is lucky enough to be never divisible by any of the first four primes $2,3,5,7$ so it tends to be prime more often than a random number of the same size. The factor of about $2.07$ seems to agree very well with the first few rows of your table, so you may want to double-check the computation of $T_{100000}$ as it seems not to fit the curve.