I am having some trouble understanding Takens' embedding theorem, and was hoping that someone with greater knowledge could help out.

Formally, the theorem goes as follows:

Let $M$ be a compact manifold of dimension $m$. For pairs $(\phi,y)$, where $\phi : M \rightarrow M$ is a smooth diffeomorphism (an invertible function that maps one differentiable manifold to another such that both the function and its inverse are smooth) and $y : M \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ a smooth function, it is a generic property that the $(2m+ 1)$--delay observation map $ \Phi_{(\phi,y)}: M \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^{2m+1}$ given by \begin{equation} \label{eq:mapping} \Phi_{(\phi,y)}(x) = \left(y(x),y \circ \phi (x),\ldots,y \circ \phi^{2m} (x) \right) \end{equation} is an embedding; by `smooth' we mean at least $C^2$.

In English it says (not necessarily using the same notation as theorem):

Suppose that a measured time series $y(1),y(2),...,y(N)$ lies on a $D$-dimensional attractor of an $n$ th-order deterministic dynamical system. The starting point obtains an embedding from the recorded data. A convenient, though not unique, representation is achieved by using delay coordinates, for which a delay vector has the following form:

$$\mathbf{y}(k) = [y(k),y(k-\tau),\ldots,y(k - (d_\text{e}-1)\tau)]^{\mathsf{T}},$$

where $d_\text{e}$ is the embedding dimension and $τ$ is the delay time. Takens has shown that embeddings with $d > 2n$ will be faithful generically so that there is a smooth map $f:\mathbb{R}^{d_\text{e}} \mapsto \mathbb{R}$ such that

$$y(k+1) = f(\mathbf{y}(k))$$

for all integers $k$, and where the forecasting time $T$ and $\tau$ are also assumed to be integers.

My issues:

The time-series lives on some $D$-dimensional attractor, so that would be equivalent to saying we are measuring some system and we record data of dimension $D$? I.e. imagine we are measuring some system of stock prices consisting of three different stocks, and we sample this price at every $\Delta t$, then $D=3$?

An $n^{th}$ order deterministic dynamical system, means that it has $n$ degrees of freedom? I don't understand what $n$ (or $m$ in the theorem actually is)?

So assuming e.g. $n=4$, then as long as my $d_\text{e}=9$ or more I can accurately map from that space back to the measured space (this is still without knowing what $n$ actually represents)?

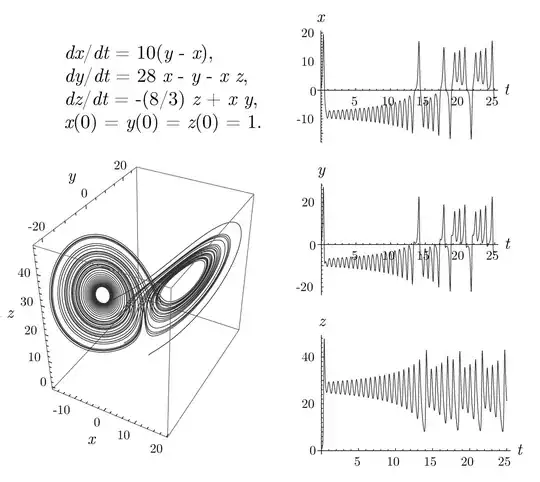

Here's some Lorenz data that might aid explanations: